Since initial reports of novel coronavirus (known in public health circles by the unsexy moniker 2019-nCoV) started surfacing earlier this week, the response on social media has ranged widely from measured caution to unmitigated panic. The latter was exacerbated by Wednesday’s travel ban in Wuhan, China, a city of 11 million people in central China that is believed to be the epicenter of the virus, as well as reports of 26 people in China dying from the disease. Two cases of the virus have been reported in the U.S.; as of Friday afternoon, authorities in France confirmed two cases in their country, as well.

We currently know relatively little about the coronavirus and how it is transmitted, explains Jordan Tustin, an assistant professor in public health specializing in epidemiology at Ryerson University. “It is important to note that we need to better understand how easily the virus can spread from person-to-person in order to better assess the risk posed to the public and globally,” she tells Rolling Stone. That said, although the virus appears to be spreading fairly rapidly in parts of China, “currently there is no cause for alarm in the United States or elsewhere and the risk is low,” she says, adding that many of the reported fatalities had preexisting health conditions.

Nonetheless, that hasn’t stopped people in the United States from circulating rumors and misinformation about the virus, with a healthy dose of rabid conspiracy theorizing and racism-tinged paranoia to boot. The fact that the virus appears to have originated in China seems to have exacerbated the opportunity to spread misinformation, says Jen Grygiel, assistant professor in communications specializing in memes and social media at Syracuse University. “When psychological states are peaked and people are anxious, they’re more apt to share [inaccurate] information,” they tell Rolling Stone. “Given the strained relations between China and the U.S., there’s even more anxiety there.”

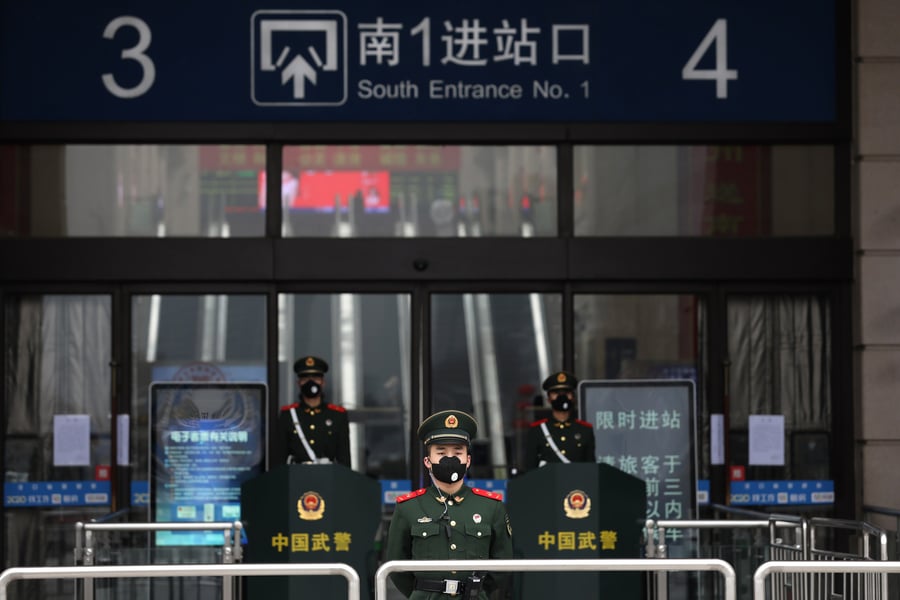

Chinese authorities have also been accused of censoring reports about the epidemic and silencing journalists, detaining them and forcing them to delete footage from a Wuhan hospital. “There’s a lack of trusted sources and a lot of control exhibited by the government” over the media, says Grygiel. Last month, Wuhan authorities detained eight people for spreading “rumors” about the disease by posting about it on social media. Such reports have justifiably heightened skepticism on social media about the official narratives issued by the government, but they also are likely contributing to a deep sense of anxiety and fear where misinformation can thrive. Here are the most common rumors and hoaxes that have spread as a result of reports of novel coronavirus, and why such misinformation tends to spread in the midst of a public health crisis.

1) The government introduced the coronavirus in 2018, and Bill Gates was also somehow responsible.

On January 21st, QAnon YouTuber and professional shit-strirrer Jordan Sather tweeted a link to a patent for coronavirus filed by the U.K.-based Pirbright Institute in 2015. “Was the release of this disease planned?” Sather tweeted. “Is the media being used to incite fear around it? Is the Cabal desperate for money, so they’re tapping their Big Pharma reserves?” This theory quickly gained traction in many conspiracy theorist circles, with QAnon and anti-vaccine Facebook groups posting links to the patent suggesting that the government had introduced coronavirus, presumably to make money off a potential vaccine.

Adding fuel to the fire, Sather followed up by linking the Pirbright Foundation to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, based on a 2019 press release announcing that the foundation would be helping to fund an unrelated project to study livestock disease and immunology. (Along with other so-called “elites,” Bill Gates is a frequent target of QAnon conspiracy theories.) His inclusion was not particularly surprising, says Renee DiResta, research manager at the Stanford Internet Observatory. “Any time there is an outbreak story with a vaccine conspiracy angle, Gates is worked into it. This type of content was very similar to Zika conspiracies,” she tells Rolling Stone.

According to a Pirbright spokesperson who spoke with BuzzFeed News, the 2015 coronavirus patent was intended to facilitate the development of a vaccine for a specific type of avian coronavirus found in chickens, which have not been implicated as a potential cause of 2019-nCoV. Further, the spokesperson said that the Gates foundation did not fund the 2015 patent, thus ostensibly negating any potential connection between the billionaire and coronavirus. But that hasn’t stopped conspiracy theorists from continuing to widely speculate about his involvement, especially following the wide circulation of a 2018 Business Insider article about a presentation Gates gave at a 2018 Massachusetts Medical Society and New England Journal of Medicine event. During the discussion, Gates presented a simulation suggesting that a flu similar to the 1918 flu pandemic could kill 50 million people within six months, adding that the global public health community was unequipped to deal with the fallout of such an event.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Gates’s presentation was in the context of a wider argument that governments need to work better with the private sector to develop the technology to fight a potential pandemic. “The world needs to prepare for pandemics in the same serious way it prepares for war,” Gates said. To a rational person, this would clearly indicate that he was arguing for better preparedness in fighting pandemics, not gleefully anticipating a potential future one — yet on social media, the article was widely cited by conspiracy theorists as a globalist billionaire ominously predicting the engineering of a global catastrophe, for no reason other than personal profit.

2) There is a vaccine or cure for coronavirus that the government won’t release

A viral Facebook post dated from January 22nd contains a screengrab of a patent filed by the CDC for what is purported to be a coronavirus vaccine, suggesting that the virus was introduced by the government for pharmaceutical companies to profit off the vaccine. While this makes no sense on even the most superficial level (novel coronavirus is, by definition, brand-new, so it would be impossible for there to already be a vaccine for it), the screengrabbed patent actually applies to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), another type of coronavirus that also originated in China and killed hundreds of people in 2002 and 2003. Although there have been reports of companies receiving funding to developing a vaccine for n-CoV, currently “there are no vaccines available for any coronaviruses let alone the (Wuhan) one,” Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Health Security, told PolitiFact.

3) Coronavirus originated with Chinese people eating bats.

Because most coronaviruses originate among mammals, and because the current working theory is that 2019-nCoV originated in a live animal market in Wuhan, many on social media have jumped to the conclusion that some Chinese people’s predilection for eating bats is putting global health at risk. This assumption has been bolstered by a number of viral videos purporting to show people eating bats or bat soup: “Does this thing look like death in your bowl?,” one tweet in Mandarin with more than 2,000 likes reads. The videos were immediately picked up by tabloids and conservative blogs, which ran such non-judgmental, non-Eurocentric headlines as, “Is this objectively disgusting soup what’s causing the coronavirus outbreak?” And social media users reacted in kind, professing their horror at the clips. “Y’all Chinese people eat this shit and expect to be fine? Cmon,” one tweet said.

Of course, while eating small mammals like bats isn’t unheard of in some parts of China, it’s also not exactly commonplace, and that claiming otherwise about a country of more than 1.3 billion people is a massive generalization, to say the least. Survey data of Chinese diners from 2006 suggests that the practice of eating exotic animals became even less common following the 2002-2003 SARS outbreak, the source of which was believed to be bats (though researchers that the virus was actually passed to humans via palm civets, a type of large cat). More to the point, there is no evidence that eating bats was the source of the coronavirus outbreak; authorities have stated that many people who tested positive for 2019-nCoV did not have any contact with live animals prior to contracting the illness, and a report from the Journal of Medical Virology actually suggests that snakes may have been the cause of the infection.

In summation, we don’t know exactly what causes 2019-nCoV yet, or how it is transmitted. But it’s safe to say that characterizing the virus as a product of an entire country’s eating habits feels both inaccurate and wildly offensive. “It’s not simply a matter of the consumption of exotic animals per se,” says Adam Kamradt-Scott, associate professor specializing in global health security at the University of Sydney, told Time. “So we need to be mindful of picking on or condemning cultural practices.” That’s especially true considering the practice of eating exotic animals stems from a collective national memory of famine and food shortages, as political economist Hu Xingdou told the New Zealand Herald. “Chinese people view food as their primary need because starving is a big threat and an unforgettable part of the national memory,” Hu said. “While feeding themselves is not a problem to many Chinese nowadays, eating novel food or meat, organs or parts from rare animals or plants has become a measure of identity to some people.”