At the time of his death, Aaron Hernandez was only 27, but he’d already lived many lives. Born to a middle-class Puerto Rican household in Bristol, Connecticut, Hernandez had been a star in athletics basically as long as he could hold a ball. And by the time he started playing football seriously in high school, everyone around him could tell he was destined to be a star.

But cut forward a few years, and Hernandez’s name was recognizable for a whole different reason. After playing for the University of Florida Gators in college (with quarterback Tim Tebow), he’d been drafted by the New England Patriots, and even managed to score a touchdown during their trip to the Super Bowl. But in June 2013, after just three seasons with the Pats, he was arrested for the murder of his friend Odin Lloyd, a 27-year-old semi-pro football player who was dating his girlfriend’s sister.

From there, Hernandez’s reputation began to crumble, and the double life he’d been leading — pro-football family man by day, wannabe gangster by night — came crashing together. In 2015, he was convicted to life in prison for the murder of Lloyd. Two years later, just days after he was acquitted on a double homicide — an unsolved case from 2012 that had been connected to Hernandez after Odin’s death — the former Patriot was found dead in his prison cell. Authorities ruled it a suicide.

His death, however, didn’t stop the questions. Who was the real Aaron Hernandez — and why did he decide to take his own life, when he was still able to appeal his murder conviction? Soon, even more began to pile up — like rumors that he was secretly bisexual and that chronic traumatic encephalopathy (a brain condition, better known as CTE, which is caused be repeated concussions) might have been a factor in his deteriorating mental state.

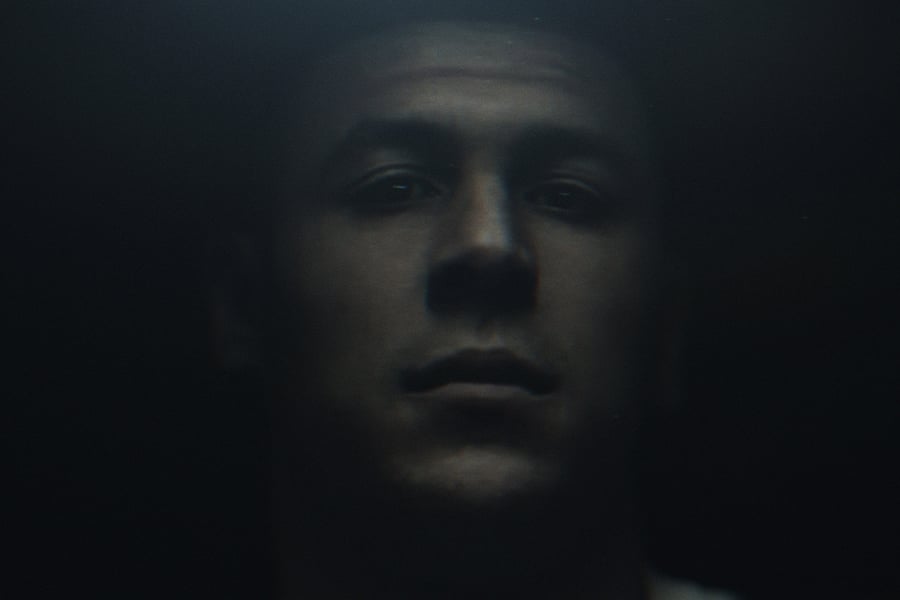

In their new documentary Killer Inside: The Mind of Aaron Hernandez — which premiered on Netflix this week — director Geno McDermott, along with executive producers Dan Wetzel and Kevin Armstrong, don’t exactly answer these questions, but they do provide plenty of insight. Incorporating dozens of interviews with journalists, players, and those close to Hernandez and Odin — as well as actual audio of Hernandez’s phone calls with his loved ones from prison — Killer Inside offers a rounded, insightful look into one of the most confounding figures in sports history. We caught up with McDermott to talk about how the docuseries came together — and how hard it is to present different sides of a story, without the satisfaction of a conclusion.

What got you interested in doing a story about Aaron Hernandez in the first place?

I had met with [sports journalists] Dan Wetzel and Kevin Armstrong, and they had been covering Aaron all the way back through high school, before any sort of foul play. And I met them going into the second trial. I felt like everyone had forgotten about Aaron, and I felt like it was a very important story to tell because everyone just wrote him off as someone who was going to be convicted again, and spend the rest of his life in prison. I do tell a lot of true-crime stories, and I played a lot of sports growing up. And it was just something that I was fascinated by, and that’s why I dove into it.

I understand that this is kind of the second iteration of this project.

I started making this film in 2017, and I self-financed it, so it was really trying to make the best we could with a little bit. And we ended up making a really great film over the course of about a year and a half. We put it into the DOC NYC film festival, and we got some really good exposure. And then we partnered with Netflix and made it into a multipart series, which when I started, my dream was to have this land on Netflix and be one of Netflix’s great true-crime docuseries. Going into DOC NYC, Netflix was already looking at it. And shortly after is when we decided to partner together, and we went right into production on the three-part series. It was 90 minutes, and now it’s a little bit over three hours.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

One of the most powerful parts of the film is when your interviewees speak about Aaron’s sexuality — you interview Dennis SanSoucie, his former lover in high school. Why did you leave it out of the first version?

Because it honestly didn’t feel like [the rumor about Hernandez’s sexuality] was substantiated at that time, and we ran out of resources. By the time it was substantiated, we basically had to finish the film. We couldn’t just keep shooting and miss the festival. It was the best we could do with the amount of time and resources we put into it. So that’s kind of how that landed that way.

What was the experience like, going back and reporting that side of the story?

Well, a big thing for us was to get an interview with Dennis SanSoucie, who was Aaron’s really good friend in middle school and into high school. And Dennis talks about them having a relationship together. So when that came out, we knew we wanted to get in front of Dennis and have an interview with him. His dad, Tim SanSoucie, also gave us an interview. So being able to put that into the series was by virtue of being able to interview them and hear their perspectives. Dennis walked us through what it was like to have a closeted relationship with Aaron from middle school all the way up through high school. And then Tim SanSoucie was able to talk about the way he ran his house, why he understands that his son had to keep it quiet. So we kind of had a breakthrough there with that interview, and that kind of gave us the license to talk about that topic.

It must have been difficult to try to add in a discussion of his sexuality, while being careful not to somehow blame his actions on repressed homosexuality.

We don’t blame any of Aaron’s action on, really, anything. We made sure of that. Our goal was to present all these topics, and all these kinds of themes. And one theme was sexuality in sports. And in talking to Tim and Dennis — and Dennis talking about how tough it was to be bisexual growing up, being in such a male-dominated world like football — that kind of pushed us into interviewing somebody like Ryan O’Callaghan, who’s a former Patriots player. And he’s an outspoken, gay-rights activist, just from being on the Patriots and not being able to really say anything. So that’s kind of how we talked about that topic.

In the film, you point out that a Boston sports-radio station outed him just two days before his suicide, but you don’t make much of it. I thought it was interesting because it would be very easy for someone making a different kind of documentary to link those two. But you didn’t really dig into that, and I was wondering if you just saw that there wasn’t much of a connection.

I think, again, it’s because we’re making a definitive docuseries here and not a salacious TV special where we’re pointing the finger at certain things. That’s why when we just present things as they factually are, and don’t preach some sort of agenda with it and point the blame somewhere. Because that’s really not what we wanted to do. We wanted to present everything, present all the facts, present as many perspectives as people would give us in interviews. And it’s really up to the viewer to make a decision on who they blame, what they blame, what could it have been.

And I think that’s what continues to fascinate America about the story, is that it’s really hard to put your finger on something. Every time you put your finger on one thing and you think, “Oh, that could be it,” then you start thinking about the six or seven other factors that play into it. It just seems to never end. Whereas a lot of other true-crime stories, they end. There’s a conclusion. This seems to continue to reveal new details and information. And it’s a very complex story to tell.

I think what stands out to me about this series is that it’s one of the most comprehensive true-crime documentaries that I’ve seen about something this recent. A lot of the longer documentaries have to do with crimes that took place a decade, two decades, 50 years ago. Given your experience working in true crime, I was wondering if that presented any challenges?

Yeah. That’s a really great question. Take Aaron’s prison phone calls, for example. When we first started making the film, those weren’t available to us. But as more time passes, things like that become available.

The phone calls in prison, you mean?

Yeah. So, as soon as Aaron had taken his own life, we kind of thought, “Oh, we should start going after these.” We started putting in [FOIA] requests, even before the second trial, and we kept getting denied. Because at a certain point, you just give up. And then we finally looked into it again, just before we finished up the [first] film and were talking with Netflix, and they became available.

So it’s a gamble: There’s pros and cons. We started getting interviews before the second trial, and that helped because the Aaron Hernandez story had cooled off, because he was already convicted of murder. So a lot of the press had forgotten about him. They wrote him off like, “Oh, he’s going to get convicted again at his second trial.” And then he was deemed not guilty, and then took his own life.

I think if you wait five, six, seven, eight years, 10 years, maybe you get a different set of interviews. I don’t know if it’s a better set or a worse set; it’s something impossible to predict. Some people need more, and then they’ll give interviews. And others, you got to get them right in the moment.

Could you speak to what you saw as Aaron’s father’s role in his life, and do you think that’s a turning point for him?

Yes. Everyone that we talked to will say that that was a huge turning point — because Aaron’s dad was really the structure in the house. And when he passed away from routine hernia surgery, it was totally unexpected. It just really was a turning point for Aaron, because he had lost the structure in his house. So that’s when he decided to not go to [the University of Connecticut], and play with his brother. He went down to Florida to play for the Gators. I think that’s when the double life started to develop, after his dad passed away. He started to kind of yearn for that double life — be the all-star athlete, be an amazing football player, and family man during the day, but then it seemed like at night he would change over. And I think that was a critical point, when his father passed away.

And given that you started working on this when Hernandez was still alive, had you tried to interview him?

So, we didn’t. Our plan was to wait for the second trial to be over, and then to put in the request. And that was our plan. And then once he became not guilty, and the media kind of keyed into it again, it just seemed like, at that point, it would’ve been really hard to get it, because everyone was probably requesting that. And then for him to take his life a couple of days later made it not possible. So that was our plan, but we couldn’t — there was no way we were going to be able to get an interview leading into the second trial while he was in prison. It would had to have been something we got after the second trial and things settled down a little bit.

And what were your first thoughts when you heard that he had taken his own life?

I was shocked. I remember waking up that morning and…your first thoughts go toward feeling sorry for his friends and family. Because everyone that we talked to that grew up with Aaron, they loved him. So you just felt bad for everyone. And then when you start to talk to people later on and they get into when they heard that Aaron took his life, it just makes it even more tragic and heartfelt. And then you start to think about, where does this take the project? Is the project over? Are we done? And for a while I didn’t know what I was going to do. I was thinking about shutting it down. But then we decided to push through and just announce that we were doing a series.

One more thing that you added to the docuseries was his posthumous diagnosis of CTE.

Yeah. So, again, we couldn’t include something like that until his brain was properly researched and he was diagnosed with it. So at that point we felt like we had the license to be able to include it into the series, because it had been proven that he had it. And I think another reason why we included it was because we feel like CTE is just a conversation that needs to keep being had for every sport, not just football. I played a lot of contact sports growing up and hit my head a bunch of times and may or may not have had concussions. But I never remember anybody properly testing me or having any sort of protocol in place, so it was important for us to basically talk about that in the series.

And then, as it relates to Aaron, we know that he had CTE — we know that he suffered from it. And it’s horrible that he did. But, again, we’re not saying that CTE was a reason for anything. Because there’s a lot of people that have CTE and they’ve never murdered people or chosen to do bad things. That’s not something that we’re trying to say in the piece. It’s just a conversation of CTE and the fact that Aaron had it, putting it out there.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Correction: This story has been edited to clarify that Puerto Rico is a commonwealth of the United States.