Kasumi Borczyk*

What happens to a country that is afraid of loving its own land?

The Indigenous community of Warmun lies 3,000 kilometres north-east of Perth. In winter, the river-beds run dry, the midday heat emanates from some subterranean source and grass-fires erupt spontaneously here and there before disappearing like muffled screams.

Today, Warmun is home to 400 or so Gidja people whose lives are marked—in no small way—by the boom and bust mentality of the mining industry. There is Rio Tinto’s Argyle Diamond mine: producer of 865 carats of rough diamond since 1983, who have pinned an invitation to celebrate their decades long partnership onto the community’s noticeboard. There is the Ridges Iron Ore Mine whose levy bank broke in February this year, causing red ore and dust to run off into the creek that bisects the town through its centre and where children fish and play in the wet season.

Most recently, there is Kimberley Granite. In late 2019, the mining company began cursory “exploration” of a proposed site in Halls Creek, cleaving tonnes of granite out of the earth without the informed consent of traditional owners. Kimberley Granite Holdings were later denied approval to mine the Halls Creek site, but according to Warmun’s elders, the damage has already been done and will likely be done time and again.

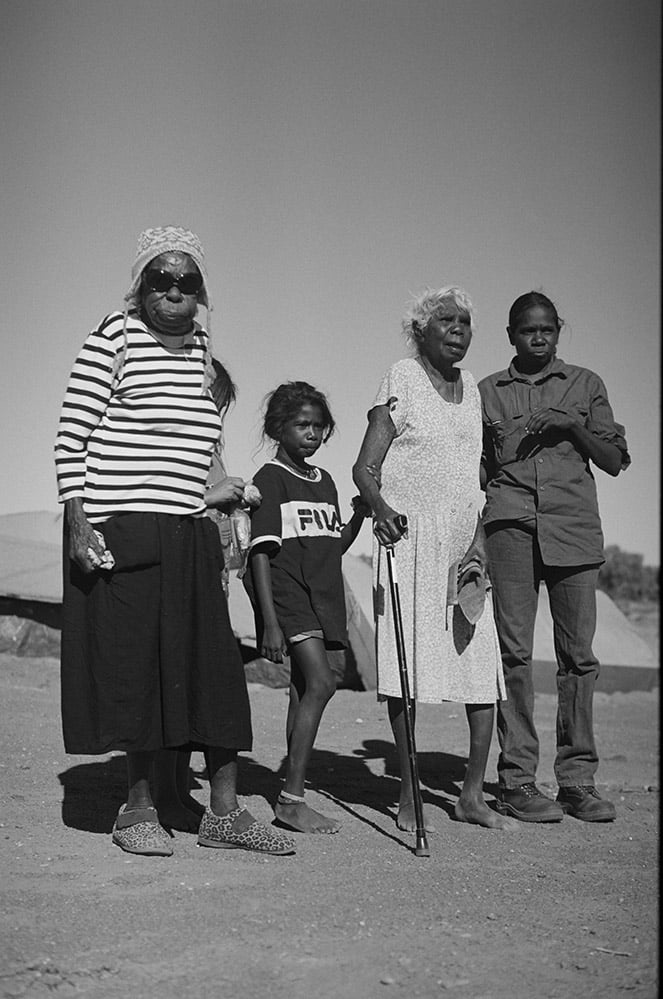

The elders are gathering their children and grand-children and great grand-children into the community’s mini-van to visit what remains of the mine site. At the turn of the 20th century, the Western Australian government set up reserves across the East Kimberleys to “educate” the starved and homeless Gidja people who had been forcibly removed from their land to make way for cattle stations. Eileen is an elder of Warmun’s community and a pre-eminent artist and storyteller of its landscapes.

Her voice is frail and thin, receding while she speaks to you as though it were travelling past you on its way elsewhere, but her face betrays an emotional stamina that only years and years of accumulated wisdom could account for. She tells me of how the elders are old enough to remember their formative years as indentured farmhands on these lands, but today, as they are returning to Country once again, driving down the Great Northern Highway, the low-lying shrubs and eucalypts bleed into a dizzying tableau of cosmic significance.

Within one continent, there are three Australias. There is the Australia of the East Coast, with its ‘F*ck plastic! Save the bees!’ tote bags and the palliative comforts of metropolitan buzz, and there is the gas guzzling and gun-toting Australia of the Western plains—whose bumper stickers are tonally closer to a personal threat than a political statement.

To paraphrase Cedric Davies, there is the Australia that is pro-mining and there is the Australia that is very pro-mining. And then there is the Australia that has not been granted the privilege of picking sides. Warmun happens to be an Australia of this third kind: an Australia forced to bear witness to the machinery of its own destruction.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Visual artists Mabel Juli (far left) and Mabel Carrington (third from left) visit the destruction left from Kimberly Granite with their family. (Photo by Kasumi Borczyk)

The destruction of sacred Indigenous sites has become something of a national past-time. Recall the Juukan Gorge debacle of 2020 where ancient rock shelters were obliterated by Rio Tinto in the Pilbara of Western Australia. Recall also, the Djab Warrung birthing trees that were bulldozed to reroute the Western Highway between Adelaide and Victoria. Over summer, the public was incensed.

Protests erupted nationwide against the continued destruction of cultural sites. “Would you blow up a Church?” people asked. “Would you blow up the Parliament house? A cemetery? The goddamn Opera House?” they shrieked. When news outlets reported that 28,000 year old tools were discovered by archeologists inside the Juukan Gorge caves, the outrage was palpable. Amidst the outpourings of anger and betrayal among inner-city coastal-elites, there was one contortion missing in the mental gymnastics that was required to feel both validated in our shock, and absolved of personal responsibility, and the landing didn’t quite stick.

What White Australia has been most aggrieved by is the sensation that they have been robbed of future possibilities for archeological, anthropological, and artistic inquiry. That the worthiness of a piece of land in Australia is proportional to its use-value is testament to the ways in which we continue to view our land as instrumentally valuable. The alternative—to consider that the land may hold intrinsic value by virtue of its very existence—runs counter to an Australia whose governments behave like a corporation and whose citizens behave like its shareholders. This is what happens to a country that is afraid of loving its own land because to love it—to truly love it—would be to reckon with what has been done.

The horizon across Halls Creek is uniform for miles until the eye catches a gigantic pile of rocks cut at unnatural angles and the mind registers a site of obvious human intervention. There is something alien about walking into an abandoned mine-site. It feels like you’re trespassing into that part of the human psyche where power interfaces with desire.

The elders pull out their camping chairs and arrange themselves neatly in a row in front of the large pit. They begin to tell stories about “going bush”, about walking across this land as children and about the loved ones whose remains have found a place to rest here. “We didn’t used to have funerals like you folks, you know,” Eileen tells me. “When family passed away, we used to put their bones between two rocks… we used to bury them here,” she says, pointing to a landscape that has been blighted by the invisible hand of the free market.

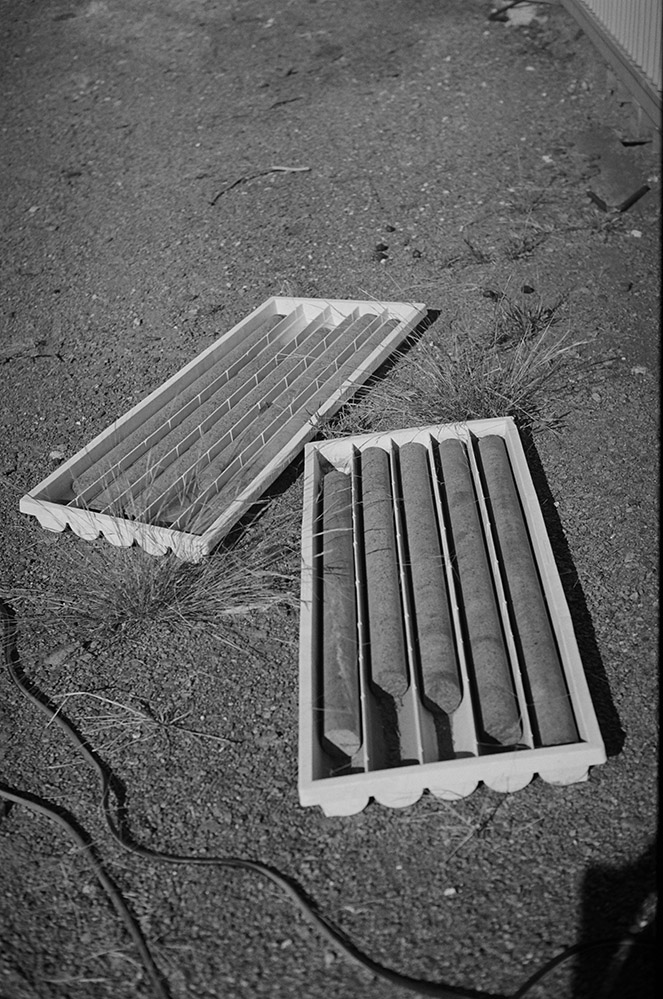

Large slabs of rock are an imposing force on the landscape that Warmun’s artists once depicted in their dreamtime paintings. (Photo by Kasumi Borczyk)

As it stands, the Native Title Act does not give Indigenous communities the right to veto mining licenses. The Native Title Act allows communities to enter into negotiations with the hope that an agreement can be reached between the two parties. In effect, it treats the protection of Indigenous land as something to be managed like an HR department where land is given an exchange-value to be bought, sold, and retroactively compensated for, once it has already been destroyed.

As James Fitzpatrick—a lawyer with over 25 years of experience negotiating some of the largest Native Title land use agreements—tells me: “The law of Native Title didn’t exist in Australia before 1992. Since then it has become, according to one senior Australian politician, ‘more complex than the Taxation Act’.

“One of the problems with the law of Native Title is that it has transferred a lot of the action that was in the hands of a political movement—Land Rights Justice—into the anaemic hands of lawyers and courtrooms, and into processes that most people, black or white, struggle to understand. There has consequently been a political dissipation of one of the most important single issues in this country for decades. At least, until the destruction of the Juukan Gorge caves by Rio Tinto.”

The business of dispute resolution rarely takes into account the fact that you’re likely dealing with two parties whose concept of the world are diametrically opposed. Indigenous elders often become embroiled in the bureaucratic organ of the state and are forced to prove their relationship to the land according to the metrics of their colonisers. Eileen shakes her head and points inward towards some inner reserve of strength. “You know, when you destroy our land, you destroy our heart too.”

“One of the problems with Native Title is that it has transferred a lot of the action that goes forward into the hands of lawyers and courtrooms and into processes that people cannot possibly understand.”

Generators, heavy machinery, temporary housing, upturned plastic chairs, and rubbish remain at the entrance of the mine-site as testimony to the demented possibilities of resource extraction. It is immediately obvious that Kimberley Granite Holdings were forced to leave in a hurry with no recourse for the mess that has been left behind. The minivan slows down to a stop on our way back to Warmun and the family members tepidly come out to explore what remains.

For several minutes the children open the dongas with a spirit of reserved curiosity as though they had stumbled upon a haunted castle of mythical proportions. There was a badminton bat, basketball, high-visibility workwear, workplace incident reports, torchlights, batteries, and a packet of condoms inside a bed-side drawer. One room was scarcely furnished except for a packet of miniature Chinese flags haemorrhaging out of their plastic packaging and onto the ground.

As we took stock of this random inventory of things, a simple truth occurred to me: that for every building erected, for every road built, another part of the world was necessarily being subtracted from. Meanwhile, the federal government has announced that its COVID-19 economic recovery plan will be “gas-led”, involving a $28.3 million dollar plan to frack the Beetaloo Basin.

Meanwhile, Rio Tinto reportedly still has 1,780 approvals to destroy sites of Indigenous significance. Meanwhile, buildings appear and home renovations are made. Meanwhile, granite bench-tops are installed as though they were forged alchemically from the stuff of dreams. The elders are planning to request that the site be properly cleaned and are discussing the benefits of trying to seek compensation for the psychic damage that has been done.

Among the rubbish left behind, cylinders of granite remain abandoned next to empty transportable housing. (Photo by Kasumi Borczyk)

Where the destruction of Indigenous land is not a bug but a feature of our nation’s design, it can be difficult to maintain hope and foresee viable solutions. I asked David Ritter, one of Australia’s leading Indigenous rights lawyers and CEO of Greenpeace Australia about prospects for meaningful change. “The Uluru Statement From the Heart gives me enormous hope, because of the beauty, generosity, and clarity of the ‘offer of a way forward’ that it sets out, based on extensive deliberation among Indigenous people across Australia. A constitutionally enshrined voice to parliament is essential. Native title became a boxed up process, but it’s still open to us as a country to go down the path of national and regional treaty making.”

In the Northern Territory, Indigenous Youth Climate Action Groups are raising awareness against the potential dangers of Origin Energy’s plans to frack the Beetaloo Basin. Nicholas Fitzpatrick from Seed Mob in Borroloola tells me that he was working as a sea ranger when he first heard about the new oil and gas projects in the NT and decided to devote his time and energy to raising awareness and stopping it. “When I got my head around it, I was very upset that the government would allow this dangerous industry in the NT. The fact that the country needs its people fighting back to protect its water and its way of life, it’s a fight that started ages ago and is still happening today.”

“When you destroy our land, you destroy our heart too.”

Eileen tells me that the elders feel ashamed for not having been able to do their job in protecting their land, as it should be protected. It strikes me as unfair that Australia’s Indigenous communities are tasked with the job of being spiritual gatekeepers within a greater community that doesn’t recognise the value of their stewardship.

It strikes me as unfair that they should feel embarrassed or ashamed for a battle that has all the chips stacked against them from the beginning. Eileen shrugs her shoulders to suggest that land stewardship is not a “job” in the traditional sense. It is not something that can be picked up in the gig economy and dropped on a whim when something more convenient comes along, but it is a way of moving through the world in lockstep with your natural environment.

I tried to imagine the lives of the men who recently inhabited these dongas and what experiences during the day shaped their dreams at night. Inside the mine site’s communal dining area was a piece of paper stuck to the wall. It read: “YOU are not the only person that lives here so clean up after yourself”.