I was recently watching a detective show called The Bridge with my Dad, and I referred to it in passing as “Scandi Noir”. He looked confused. So I explained what I meant: the booming genre of detective shows fetishising Nordic landscapes. Washed-out colour palettes. Very, very tired looking detectives in turtlenecks. He understood immediately.

My Dad was a cop back in Sydney in the Eighties, the grimy, gritty era in which Roger Rogerson took police corruption to dizzying new heights. Two bestsellers, a spin-off podcast and a TV show development deal being inked, and he’s somehow not sick of talking about his time on the force.

And then he said the wildest thing: he told me, “We make Scandi Noir look like a picnic.” I pressed him on it, and he went on to claim that as good as Scandi Noir shows are (and trust me, it’s pretty much all Dad watches), we, as a nation, deal with much darker fare Down Under. “Being a cop in the Eighties was the Wild West of policing,” he told me. “Mate… Australian crime is fucked.”

“Being a cop in the Eighties was the Wild West of policing. Australian crime is fucked.” – Ex-cop John Verhoeven

It’s become evident that crime stories from different nations go through popular booms. British crime dramas set in sleepy hamlets? Old news. Scandi noir? Look, it is starting to wear a little thin, popularity-wise. But Australia? Maybe my Dad is right. Maybe we’re the next big thing.

But why? Why are stories set here, whether books, films, or true crime podcasts, going off?

Hell, maybe it’s got something to do with the true crime boom. After all, we bloody love a murder down our way. Over half of Australian podcast fans listen to shows in the true crime genre. These devotees don’t just listen to these episodic forays into the minds of maniacs: they try to solve these crimes. To crack the case. True crime listeners are an oddity — part voyeur, part advocate for justice, part amateur sleuth, they’re voracious in their pursuits. And Down Under, they spend countless hours trying to dig for details hidden from public view.

The Mushroom Cook

“I think there’s more mystery surrounding Australian crimes due to… legal sensitivities,” says Brooke Grebert-Craig, Herald Sun investigative reporter and host of The Mushroom Cook podcast, which follows the story of Erin Patterson, a woman from the small Victorian town of Leongatha who is facing trial for the murder of three people via a lunch laced with highly lethal death cap mushrooms. “Contempt and defamation laws in Australia are quite strict, compared to other countries like the US. This restricts Australian media on their reporting of the cases, which, in turn, increases the intrigue.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

I never had that problem growing up. Dad left countless copies of the Australian Police Journal lying around the house (something my therapist and I have been dealing with for a few years now). For myself, and presumably anyone who grew up in the orbit of crime, the mystery, a lack of forensic details, wasn’t what drew us in. It was the vibe.

“The vibe?” says Dad, halfway between quizzical and irritated. “Yeah,” I say. “The feeling of the thing. The flavour.” “Well,” he replies, “I was based out of North Sydney. Not sure how much of a flavour there was, mate.”

See, Dad was a city cop. His stories always take place fanging down George Street, Sydney, or in a crowded lockup at Central. Always in the city. And in cities, people rarely know their neighbours; crimes can blend into the fabric, the noise of the crowd. But Australia is far more than just its cities, and crimes that take place outside of them become almost otherworldly.

Perhaps it’s that otherworldly quality that sees overseas audiences falling in love with fictional crimes set in Australia. And in 2016, Jane Harper’s The Dry birthed our own genre, with its own vibe. Outback Noir, if you like.

Eric Bana in ‘Force of Nature: The Dry 2’

Becoming an instant bestseller, Harper’s The Dry sees federal police officer Aaron Falk called back to his hometown in rural Victoria, by way of an ominous letter and a mysterious suicide. This town has all the ingredients for a compelling murder mystery: it’s in the middle of nowhere, and hides a pantload of secrets. And for Harper, the outback was, quite literally, a foreign place: she moved from England to Geelong, where she worked for a newspaper.

“We had a very big circulation which covered a lot of country towns,” Jane says. “And I used to go on all of these roadtrips, to visit these places… and it was partially those trips, and partially covering regional Victoria for the paper, which really planted the seed for the locations that I’d write into The Dry.”

“[The Australian landscape] not only serves narrative function, but also emotional and psychological function. It’s the landscape that makes our stories distinctive.” – Robert Connelly, film director

The cinematic adaptations of the first two Falk novels have been critical hits, in part because of their intrinsic Australianness. But what does that actually mean? What makes them so fundamentally Australian? “That’s a really interesting question,” replies Robert Connolly, director of The Dry and its sequel, Force of Nature: The Dry 2, which takes place in and around the (ironically very wet) Dandenong Ranges. “I think, obviously, Jane Harper’s books have been massively successful because they place incredible characters in this landscape, in this world of ours that is intoxicating. It not only serves narrative function, but also emotional and psychological function, too,” Connolly explains. “I think it’s the landscape that makes our stories distinctive. Unique.”

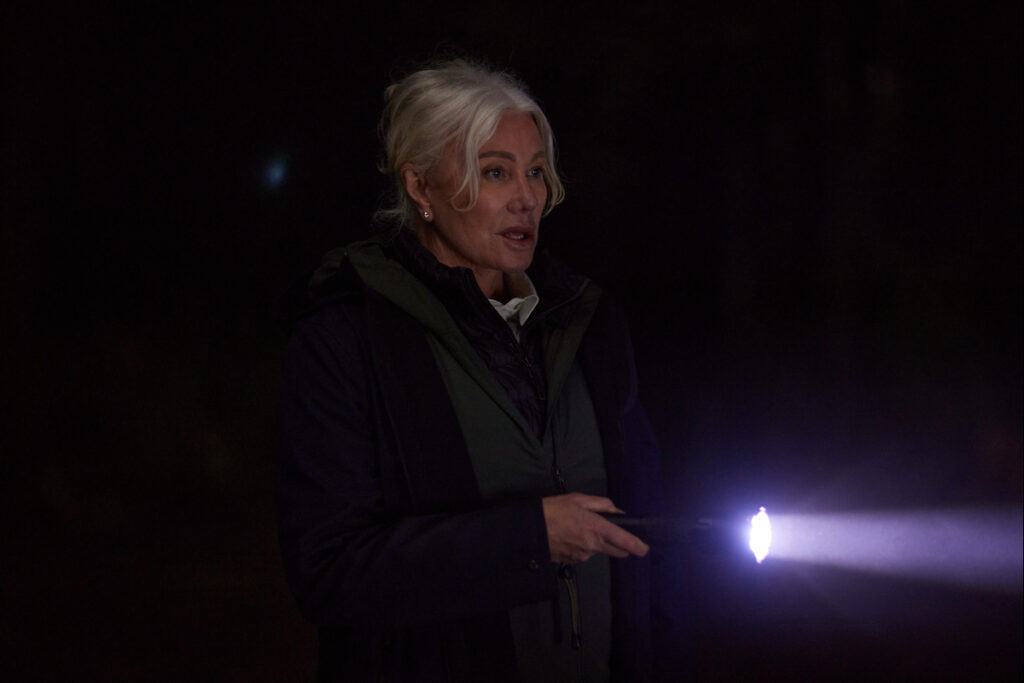

Deborra-Lee Furness in ‘Force of Nature: The Dry 2’

It’s been said that the fifth member of the Sex and the City gang is New York City itself. Australian crime stories often have the same thing going on — the landscape is an ever-present character, often dictating the action, and just like in Force of Nature, it can be mildly inhospitable. “Mildly?” laughs Deborra Lee-Furness, who played Jill Bailey in Force of Nature. “You clearly couldn’t feel our pain when you watched the film — it looks beautiful, but we were up against the elements constantly, as much as our characters were. Raining, leeches, falling in holes, I mean… we had the whole gamut. And it fed us as actors,” she says. “Because we were working in nature, you know? And we’re different creatures when we’re in captivity, and out in the wild, you know? And god… it looks beautiful, right?”

It does — there’s a beauty to our landscapes which can feel at once ripe with potential, and deeply ominous. Bestselling crime novelist Candice Fox eschewed the Outback, or the Ranges, in Crimson Lake. Her smash hit novel, which was recently turned into a TV series called Troppo, takes place somewhere which, to overseas audiences, must feel truly alien.

Nicole Chamoun and Thomas Jane in ‘Troppo’

“I chose Far North Queensland because I’d written stories set in Sydney,” Candice explains. “I grew up in Sydney. And the crime here… it’s very obvious as to where it is, but I visited up north. And I kept seeing signs saying “Don’t Swim: Crocodiles.” I never saw one! But because I never saw one, my brain thought they were everywhere. And it just seemed to me to be possible to create a more subtle and beautiful type of crime, you know? That wasn’t so obvious. I felt haunted by these sorts of things! And that’s what I wanted. The atmosphere of being haunted, of secrets.”

I ask Fox whether that’s part of the appeal for overseas audiences. Maybe they feel a pull towards stories set in environments they know nothing about, and can’t comprehend. And perhaps people are drawn to Australian crime stories because of how isolated we are.

“If you break down in the middle of the Outback… anyone could come along. And I love that as an aesthetic, and a place to have stories take place.” – Candice Fox, author

“That’s all true,” Candice says, nodding. “With those far-out places in Australia, they talk about space, and say that out there, no-one will be able to hear you scream. There are parts of the Australian landscape that are absolutely like that! If you break down in the middle of the Outback… anyone could come along. There are black spots out there where you can’t get reception. And I love that as an aesthetic, and a place to have stories take place. Because you can not only contain the suspects, but you can block off all the avenues of escape. Because there’s really nowhere to run to out there.”

So there’s one convincing argument for why our crime stories are popping off right now: where they’re set. But you can’t have a crime story without someone trying to solve the crime. And no matter how visually distinct the setting, these stories would be nothing without heroes to head out there and seek justice.

Typically, that means law enforcement. And yes, there are myriad fictional detectives: Columbo, Sherlock Holmes, hell, even Jessica Fletcher, all of whom have unique skill sets, heightened traits, eccentricities. Eric Bana’s Aaron Falk, by comparison, is truly grounded. It’s as if the stories he’s in don’t want to make too much of a fuss about him, and don’t want him to have tickets on himself. Perhaps this naturalistic approach is what makes him so uniquely Australian.

Tony Briggs, Eric Bana and Jacqueline McKenzie in ‘Force of Nature: The Dry 2’

Force of Nature sees Falk grappling with a quiet, growing distrust of authority, even an authority he represents, and this feels quintessentially Aussie. “I do think there’s a real sense of responsibility that Falk feels,” says Bana. “It’s a real, and massive sense of responsibility he feels, and it kind of informs a lot of his character, and where he’s at in the world. It has him questioning the type of work he’s doing, and how he goes about it. You know, Falk wrestles with the morality, the ethics of what they [the federal police] ask people to do.”

“[My character in Force of Nature: The Dry 2] wrestles with the morality, the ethics of what they [the federal police] ask people to do.” – Eric Bana

I ask Bana if he sat down with real law enforcement to get any pointers. “We got a little bit of info,” he tells me, “but that kind of stuff can be both helpful and a hindrance, when it comes to research. I mean, you’re trying to cover your bases so that you don’t look like a fool, but at the same time… there’s a sense of ownership you gotta take, and a responsibility you have to take as an actor. ‘Cause at the end of the day, if the audience isn’t convinced by what I’m doing, it doesn’t matter if what I’m doing is technically accurate, right?”

Aaron Falk does have decidedly Western traits — he wanders into town, a lone lawman in a far-flung frontier. A maverick. Another lone lawman up against it, albeit in the comfort of a courtroom? Brett Colby, the barrister at the centre of Foxtel’s The Twelve. Colby is played by Sam Neill, giving the best on-screen barrister turn since Rumpole of the Bailey, the iconic British series which followed a gregarious QC and his misadventures in court. I tell Neill this, and he laughs.

“Oh, that’s very kind of you. In fact… I worked with Leo McKern [Rumpole himself]. Lovely man, just lovely. He was Australian! He only had one working eye, actually. And…” Sam looks off, laughing. “He had this Porsche, this incredible car. Very powerful, it was. And he’d drive it very, very fast to set… with one working eye. Terrifying, just terrifying.”

Kaila Ferrelli, Sam Neill, Frances O’Connor and Jennah Bannear in ‘The Twelve’ S2.

In The Twelve, Neill’s Colby contends with a jury of people pulled together and seconded into a room to decide the fate of the accused. “People like to assume a jury is a blank slate,” explains Sam. “But… they aren’t, they can’t be. They’re people, like us, and they bring all of their baggage to the room. And let’s face it… being trapped in a room with eleven other people, many of whom you’d not want to spend time with in normal life? That can’t be easy!”

Sam leans forward. “And then there’s Brett. Look, he’s a gasbag, he talks a lot… but he’s very smart, highly intelligent. And his heart’s in the right place. He’s very good at his job, which, actually, is a form of acting. And we do get to see a great deal more of him outside of the courtroom this season, too, which we didn’t get to see last season. He’s had multiple failed marriages — not sure what that says about him as a person — but we see him in the outside world a lot more. I’m really very happy about that.”

“Oh, like with teachers,” I remark. “I always thought it was weird seeing teachers outside of school, in normal clothes. That always really unsettled me.”

“Yes!” exclaims Sam. “In shorts! God forbid!”

Whilst Bana’s Aaron Falk drew on Jane Harper’s novels, Neill crafted Brett Colby from sources somewhat closer to home. “You know,” he tells me, “Brett is actually based on three real people. Three friends of mine, all QCs… or KCs, as you’d say now, after the change of management. Well anyway, I based him on all three of them — three very “clubbable” barristers, you might say. All wonderful people.”

“Did you get permission?” I ask. He guffaws. “Yes! Yes, I did.”

At this point, Sam raises a hand. “Sorry, sorry,” he apologises. “I should go and stop my dryer. You don’t need that going on all through the recording.” A minute later, he returns. “Sorry about that. Actually, I remember doing the same thing with my agent on a call once. And he yelled, ‘Why are you doing your own drying? YOU’RE SAM FUCKING NEILL!’.” He laughs. “Then, the same thing happened in LA, when he found out I was driving around in a VW Golf. ‘Why are you driving a Golf? YOU’RE SAM FUCKING NEILL!’.” “Should have gotten a Porsche,” I reply, and he cackles like Brett Colby would, were he the sort to indulge in such a display.

In The Twelve, it’s up to the jury to seek answers and render a verdict. It’s a noble idea, but it also scratches a primal itch we have — vengeance. We want those who carried out evil acts to be punished.

And that’s a decidedly cowboy-ish notion, one regularly portioned out by the heroes of Australian crime dramas, whether they’re slinging a gun or a gavel. I tell Fox about my Dad’s description of Australian policing in the 1980s as “the Wild West”, and she lights up. “Yeah. I think that’s spot on. There’s stuff that goes on out there, even today, that you just don’t hear about. And it pops up in the news every now and then — cops doing things to people in custody, for example, but for every incident we hear about, there’s an entire culture of it that scares me to think about.”

Mitch Jennings is the author of A Town Called Treachery, a brilliant new crime novel set in a small fictional town in New South Wales. “I didn’t set out to write a crime novel!” he tells me. “I actually wanted to write a novel that explored father-son bonds, family, and the intergenerational trauma that can form, and affect relationships… and then, it evolved into a crime novel. So I had that happen, and worked backwards. But once I realised this is what I was writing, I had to familiarise myself with the canon, I guess you’d call it. So I went back and read all of Peter Temple’s books, and I found that quite affirming. The language that Peter Temple used, in Jack Irish, in Broken Shore, that type of stuff… it informed what I was writing, more than the contemporary stuff we’re seeing — as much as I love it, and I read it as voraciously as everyone else! I think the tropes of Australian rural crime really make it easy for people to ground themselves and find their feet in the world you’re creating. I think it’s having such a moment now because it can seem, from the outside, formulaic, but I think the possibilities are sort of endless once you enter that world.”

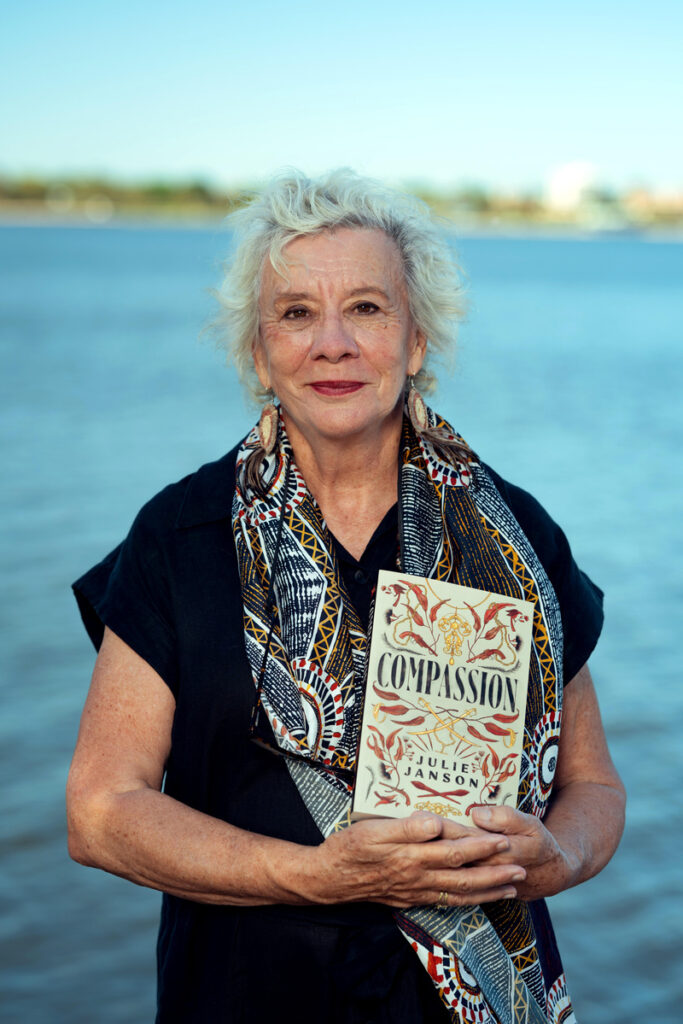

Julie Janson

“The whole of Australia’s a crime scene, in terms of invasion. So there are countless stories to be told.” – Julie Janson

Indigenous author, poet and playwright, Julie Janson, created the Indigenous crime novel Madukka the River Serpent, and her thoughts on how our country informs our crime stories are particularly on-point. “It’s so old!,” she exclaims. “We’ve got sixty-thousand years of Aboriginal habitation. The fact that the country has this ancient history really permeates my way of viewing the landscape. I mean… the whole of Australia’s a crime scene, in terms of invasion. So there are countless stories to be told, and I usually do tell a more serious story in all of my novels, of some horrible scene of massacre, of destruction, of Indigenous people. But I also like to celebrate the humour of Australians, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal… shocking, dreadful, dry senses of humour, we’ve got… and I think we should share that with the world!”

Shocking, dreadful, dry. All apt descriptors of where many of these stories take place. Fox again raises the spectre of cops, stationed in the middle of nowhere, of the shocking, dreadful, and dry. “I mean, who’s gonna hold them accountable? And more than that: who’s gonna go out there and replace them, if they’re held accountable and moved on?”

And maybe that’s it. Maybe that’s the thing that binds together all of the elements which are making Australian crime stories, real and fictional, so profoundly appealing right now, the world over.

We’re a frontier.

Our crime stories take heroes, who wouldn’t feel out of place in a Western, and give them a mystery to solve. Then, our stoic traveller is hit with a sensation, a feeling. A vibe. And whether they’re standing in a courtroom, a city street, a rural farm, a rainforest or somewhere way up in Northern Queensland, they begin to suspect that this country is a hair’s breadth from bucking them off. They’re almost screwed, all the time. Everything is so close to the surface. They’re cut off, and they’re never entirely safe. They’re a sheriff without backup. And when you roll all of these elements together, you get something singularly unique. Dad’s right, dammit. How the hell could Scandi Noir hope to compete with that?

So I call Dad, ready to eat humble pie. And I tell him that I get it now: that nothing looks, sounds or feels quite like crime stories which take place Down Under. There’s a pause. And then, three words, delivered — appropriately — in the most laconic Australian manner possible.

“Told you so.”

This article features in the September-November 2024 issue of Rolling Stone AU/NZ.

Whether you’re a fan of music, you’re a supporter of the local music scene, or you enjoy the thrill of print and long form journalism, then Rolling Stone AU/NZ is exactly what you need. Click the link below for more information regarding a magazine subscription.