Harvard Brainbow Laboratories

The prospect of mind uploading, and by extension, living long after death is enticing, but is it too good to be true?

A few hundred years BC, Chinese emperor Qin Shihuangdi’s alchemists prescribed him potions laced with mercury and gold in order to stave off death. A few thousand years later, and on the other side of the world, Luigi Galvani believed he could reignite the spark of life by sending Ghostbuster-grade blasts of electricity through fresh corpses in a practice known as Galvanism. These are just a few in a very long, very spurious line of attempts to solve the death problem – something we’ve been obsessed with doing ever since we’ve been writing things down, and let’s face it, for probably a lot longer than that.

Despite a long history of failure, quests for the holy grail are of course ongoing. Currently, there’s the ‘longevity drug’ crowd who take a combinatorial approach that involves ingesting complex experimental compounds designed to kill off ageing cells and injecting themselves with plasma concentrated from umbilical cords. Then there are the ‘brain freezers’ who have signed up and paid the measly sum of a few hundred thousand (US) dollars to have their brains cryonically preserved by an Arizona-based company called Alcor.

The idea being to reanimate the frozen brains at some undisclosed point in the distant future, giving new meaning to Bruce Springsteen’s line in “Atlantic City” – “Everything dies baby, that’s a fact / But maybe everything that dies someday comes back.” Alcor gives the prospect of reanimation a “non-zero chance” of ever happening.

Arguably the most cutting edge and auspicious of these modern day immortality projects, though, is unfolding in the labs and offices of another globally dispersed sect of transhumanists. To the layperson, it’s most frequently referred to as either ‘mind uploading’ or whole brain emulation. What it involves, to put it overly simply, is transferring the contents of our brains to silicon-based platforms that make it so we retain consciousness and essentially never have to die. Ever tried to sit through the TV series Altered Carbon? If so, then you more or less have the idea.

“What it involves, to put it overly simply, is transferring the contents of our brains to silicon-based platforms that make it so we retain consciousness and essentially never have to die.”

Enormous amounts of money has poured into the space in recent years, along with some very bright people. Still, the question has to be asked: Is mind uploading really just another doomed-to-fail immortality sham like that of emperor Qin, whose steady intake of mercury and gold took him only as far as the ripe old age of 49?

Or Galvani, whose electrocuted corpses twitched around for a while before laying stiff once and for all? Or is there a lot more to it than all the carnival-bizzarro spectacles and coloured-water elixirs of the past combined? In other words, are we finally on the fast track to hacking the biggest life problem of all – death?

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“Are we finally on the fast track to hacking the biggest life problem of all – death?”

I recently sat down with Peter Xing to get some answers. Xing is the co-founder of Transhumanism Australia, a self-described society of technologists who create a “positive impact by applying emerging technologies to global challenges.” He also works at KPMG on automation projects looking, as he describes it, at ways of “lifting up humanity and letting the robots do the work eventually,” and is a part of the faculty at Australia’s chapter of the Singularity University, where the focus again is transhumanism and emerging technologies.

A relentlessly upbeat guy who has mastered the nu-speak of tech entrepreneurialism (terms like “fidelity loss”, “new verticals”, and “local minimums” roll out of him constantly), Xing talks fast and flits between subjects at such lightning speed that trying to keep up can get dizzying. Honestly, I came away feeling a bit like I’d just spoken to an obscurantist and new wave tech-evangelist who says a lot of fancy sounding stuff without actually saying much at all – and there is a little of that to Peter Xing.

On the back of a question about his fear of death, for example, he said that for him, “There are so much unknowns [sic] in physics even, in terms of the theory of everything. What’s expanding out of the universe? Is it a multiverse? Are we in a simulation?”

Mostly, though, my first impressions of Peter Xing were wrong. On listening back to the recording of our chat, I found him both lucid and direct. Turns out I’m just too slow to keep up without the help of a recorder – a sure sign that I’m in need of a good hard dose of jacked-up digital neurons as soon as they come on the market, thanks.

On the question of mind uploading – mapping the brain, reducing its activity to computations, reproducing those computations in code, then transferring that code to a silicon-based platform that doesn’t decay – Xing is a little over 50% sure that we’ll see it happen in the next half century or so. “It’s always hard to have conviction around the future, because you don’t want to sound like a sort of religious type,” he says. “But it is based in physics.”

Underpinning Xing’s confidence is Moore’s Law of accelerating returns, which holds that computing power essentially doubles every 18 months or so, and has done so since 1965. If technology continues to accelerate along these lines – and Xing doesn’t see any reason why it will stop – then there’s nothing to suggest we won’t get to a point where the massive amounts of data generated by the human brain can be processed and digitally recreated. It’s a view perhaps most famously linked to controversial American futurist and inventor, Ray Kurzweil.

Kurzweil’s name came up a lot in my conversations with Peter Xing and other transhumanists. A prominent writer, public speaker, inventor (of groundbreaking text-to-speech technology, among many other things), and technology prognosticator, one could make a strong case that Ray Kurzweil has been the key figure in converting a new crop of thinkers like Xing to the mind uploading cause. The Singularity University, where Xing is on the faculty of the Australian chapter, was originally co-founded by Kurzweil in Silicon Valley. Finding Ray Kurzweil, Xing says, was when “the whole thing started to make a lot of sense.”

Naturally enough, Kurzweil calls this moment when we integrate with machines and blast off into a superintelligent future, the singularity. With Moore’s Law continuing to take effect, he predicts that within the next 30 years scientists will be able to understand and reverse-engineer human-level intelligence, and from there, the machines themselves will improve on it. As he writes in 2013’s How To Create A Mind, “A nonbiological neocortex will ultimately be faster and could rapidly search for the kinds of metaphors that inspired [Charles] Darwin and [Albert] Einstein. It could systematically explore all of our overlapping boundaries between our exponentially expanding frontiers of knowledge.”

Peter Xing, the co-founder of Transhumanism Australia (Photo: Simran Gambhir)

According to Peter Xing, we’re starting to see serious advances toward this future already. The first example he gives is Neuralink, a company working on what he describes as the cutting edge of brain-computer interfacing systems. “With Neuralink, it’s invasive,” Xing says. The idea is to create synthetic neurons and implant them, and “have this combination of synthetic and organic neurons working together.”

“Right now they’re essentially able to read and write to about a thousand neurons,” Xing says.

There’s also Teslasuit (not to be confused with Elon Musk’s Tesla), a company that makes a product called a haptics suit, which Xing calls, “the next level towards brain-computer interfaces, where you can actually feel in virtual reality.” To break that down, what the suit effectively does is recreate physical experiences in virtual reality. So if, for example, you get punched in a video game and you’re wearing the haptics suit, then it will actually feel like you’re getting punched in real life. Although, there is of course a built-in function that enables users to dial up or down the level of realism, as it were, depending on how game they’re feeling.

“It does initially feel like you’re being electrocuted,” Xing says of putting the suit on for the first time. “So it’s like, great, you’re paying for this ten-thousand dollar suit so you can feel like you’re in an electric chair. But if you dial it down you can simulate the rain drops, so it actually feels like rain falling on you.” The suit also comes with hot and cold packs baked in, making it so, Xing says, “you can pretty much simulate the heat you’re feeling in a bushfire or an actual building.”

There’s the obvious gaming play attached here, but, as Xing is quick to point out, the main focus of Teslasuit is not video games, it’s enterprise training. The military, for instance, might use Teslasuits to simulate the feeling of being shot or fragged by a landmine. “And that really helps to retain a lot of the experiences in your memory,” Xing says; or as the company itself puts it, “Electro-stimulation improves the learning experience by increasing immersion, fostering 360-degree awareness, and engaging muscle memory.” Just another good reason not to join the military, if you ask me. If the trauma of getting shot at, or actually shot, in the field wasn’t already enough, now they’re going to give recruits that feeling in training as well, just so they know what to expect.

“So you have your VR, your haptics suit, your gloves (another reality simulation product made by Teslasuit), that’s already Ready Player One,” says Xing. “Soon you might have Ready Player Two, and that’s the brain-computer interface coming out next. We’ve seen Gabe Newell from Valve (a giant in the gaming space, with titles including Half-Life and Counter-Strike), essentially saying that he’s working on brain-computer interfaces initially for the gaming industry. He could create reality that’s even more real than what we’re feeling right now because it’s able to tap in directly to the brain.”

Of course, these steps toward brain-computer interfacing have only strengthened Xing’s belief in the coming singularity predicted by his mentor, Ray Kurzweil. “It’s more every day,” he says. “We’re no longer this sort of fringe movement. All of Silicon Valley, and all the technologists out there, are essentially trying to solve these problems.”

“We’re no longer this sort of fringe movement. All of Silicon Valley, and all the technologists out there, are essentially trying to solve these problems.”

How will mind uploading actually work though? What are the nuts and bolts of transferring our brain’s structure, and most importantly our consciousness, to a digital platform?

One way Peter Xing sees it working is through advances at Neuralink and other similar companies. Not only does the Neuralink technology aim to combine synthetic and organic neurons, it opens up the possibility of gradually replacing those feeble old biological neurons with much more robust artificial ones over time. “They could slowly replace your biological neurons with synthetic ones, while still retaining a stream of consciousness. Then eventually you can get to the point where all of it gets transferred while maintaining that same consciousness.”

“If you apply Moore’s Law of exponentials to Neuralink, then in 30 years you’ll have more neurons than there are in the human brain. So there’s a decent pathway there,” says Xing.

Dr Avinash Singh, a computer scientist and postdoctoral fellow in the Artificial Intelligence lab at the University of Technology, Sydney, and a fellow member of Australia’s Transhumanist Society, is a little less optimistic about the idea of a seamless transfer of consciousness from the brain to a computer. Singh is another Kurzweil acolyte and a big believer in the idea that Moore’s Law will eventually bring us to a complete technological rendering of the brain, but, he says, “emulating the brain and mind uploading, there’s a slight difference here.”

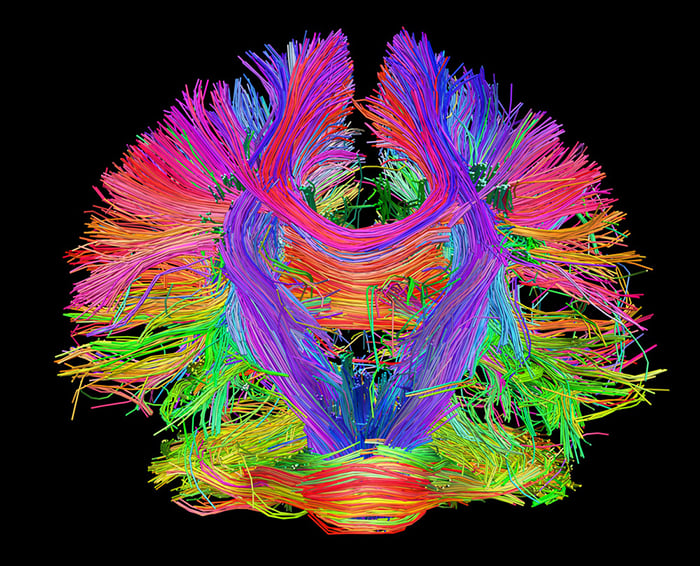

(Photo: Harvard Brainbow Laboratories)

According to Singh, what we might end up with, once hardware capacity becomes sufficient for processing the information output of the brain, is a full-scale simulation of brain function. Transferring our actual consciousness to it, however, is another matter entirely: “When we talk about consciousness, about ‘being someone’, maybe these come down to a molecular level, a cell level, and we don’t know about those well enough yet.”

In that case, what we’d have is a simulation of, say, Singh’s brain that might well mimic his behaviours and branch off into a form of consciousness all of its own, but Singh himself would continue to decay and eventually die. “That simulation is likely to happen, but I have no idea whether a person’s ‘personality’ will translate.

If we’re talking in those terms, I think we need some sort of combination of biological and electrical sides; more of a hybrid approach. Not even that. We might need to follow exactly what nature has created for us to come up with that kind of output.”

For Peter Xing, a simulation of the brain isn’t good enough. “If you’re just creating a copy of it, that won’t be the same continuation of a consciousness. So you pretty much die and there’s this other version of you that has the same information, but it’s not the same sort of stream of consciousness. For everyone else, they can’t tell the difference, but for you that doesn’t really end well.

So it’s kind of like the idea of quantum teleportation, which ends up with the destruction of atoms themselves and there’s no continuation of the stream of consciousness. The way that you could get around that is through these brain computer interfaces like Neuralink.”

“They could slowly replace your biological neurons with synthetic ones, while still retaining a stream of consciousness. Then eventually you can get to the point where all of it gets transferred while maintaining that same consciousness.”

At times, it felt like my conversations with Xing and other transhumanists were occurring in a vacuum that’s detached from all the messy reality. In other words, like all the ideas were coming from a group of computer scientists and software engineers who have no real perspective on what many call the “wet work” aspects of hard brain science.

This is a criticism that’s been leveled at Kurzweil, and others like Peter Xing, by biologists and neuroscientists many times over the years — that they lack a biologist’s grasp on the brain’s sheer complexity, and are well out of their depth as a result. In recent years, though, the scientific and medical establishments have cooled a little on such critique, and at the same time, started to take some steps to more closely align with the futurist-transhumanist crowd.

Professor Matthew Kiernan, for one, thinks mind uploading could be on the horizon. Kiernan is a renowned Australian neurologist with a list of titles and chairmanships so long it’s a wonder he doesn’t have an OBE already. “I’m not thinking that this is totally out there, or total bullshit, basically. There is rationale behind it,” he says. “The suggestion at this stage of putting in a plug and downloading brain information or backing it up, that is futuristic, but you can see it’s conceivable.”

As with Peter Xing, a good part of Kiernan’s optimism comes down to developments he’s seen both inside his own laboratories at the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre where he is co-director, and around the world in recent years. “There have been tremendous steps taken in understanding brain function, and a lot of investment in brain-computer interfaces,” he says.

“As a case in point, a clinical trial that we’re about to start here is called Stentrode, and it’s actually an invention that puts a stent up into the main blood vessel of the brain to basically try to mimic some of the situations through electrical activity. We know the brain is an electrical organism. The question we’re asking is, ‘Can we manipulate certain electrical activity to drive certain processes?’, and we know now that you can do that.”

Also ongoing at the Brain and Mind Centre is a clinical trial to insert stem cells into the brains of dogs with dementia. “They say they’re curing dementia, but we’re not exactly sure what that means yet,” says Kiernan. Then there is the project to combine over 28,000 MRI scans in order to gain a clearer understanding of how neural connectivity works. None of these projects would be possible without the leaps and bounds technology has taken in recent years, and Kiernan only sees the sophistication of such programs increasing with further exponential growth. “Again, how close it actually gets to, say, a USB in the back of the ear downloading, I’m not sure.”

“How close it actually gets to, say, a USB in the back of the ear downloading, I’m not sure.”

If you’re gunning for a brain upload these developments might sound encouraging. When we cut back on all the noise and enthusiasm, however, how close are we really to the ultimate goal?

Director of the Centre of Regenerative Medicine and Neuroscience at Sydney’s University of Technology, Professor Bryce Vissel, described the extent of our current understanding of the brain to me like this: If our brain was planet earth, then we understand about a pin-prick in the planet’s worth of information about it. Ever concerned that he was being either hyperbolic or slightly inaccurate – ever the scientist, in other words – Vissel was quick to add that he’s nevertheless very encouraged by the progress he’s seen since he started in the field some 30 years ago, and in particular by the progress made in the last few years.

He’s not alone in adopting a position of very cautious optimism and humility when it comes to our understanding of the human brain. Neuroscientist Gary Marcus from New York University suggests we’re still at a complete loss to explain just how the human brain does anything but the most elementary things. “We simply do not understand how the pieces fit together,” he wrote (in 2015, mind you).

Even Matthew Kiernan, who is on the whole pretty positive about the idea of reaching a point where we will be able to upload our minds, has to agree: “I think he (Marcus) is a realist and that’s the reality.” These are by no means outlying points of view; it would even be fair to say that the ‘we still know nothing, or next to nothing’ mentality remains the default position across the neuroscience community at large.

Prior to his death in 2018, Paul Allen, founder of the Allen Institute for Brain Science and co-founder of Microsoft, wrote: “The closer we look at the brain, the more levels and greater degree of neural variation we find. Understanding the neural structure of the human brain is getting harder as we learn more.” For Allen, this amounts to a curbing of any notion that a singularity is even remotely within reach: “By the end of the century, we believe we will still be wondering if the singularity is near.”

Recent projects towards digitally recreating the human brain would seem to bear out Allen’s point. In 2013, Europe’s Human Brain Project (HBP), funded to the tune of an eye-watering one billion euros, set out with the explicit goal of reverse-engineering the human brain and providing a full molecular simulation, all within ten years. Progress was slow from the outset.

By 2014, roughly 750 researchers had signed on to an open letter to the European Commission condemning the project’s shifting goals and lack of transparent leadership. A year later, an official mediation committee agreed with critics, requesting that the HBP refocus its efforts “on a smaller number of properly prioritised activities” and restructure its systems of management.

SCIENTISTS AT Harvard’s Center for Brain Science have developed a technique called “Brainbow” to map the brain’s trillions of nerve cells and synapses in exquisite detail. By making a 3-D dataset of high-resolution images like this one, scientists can reveal neural connections like never before. (Photo: Harvard Brainbow Laboratories)

As 2020 rolled around, the HBP was basically in a state of free fall, according to a piece in The Atlantic, with hardly anyone from the neuroscience community able to list one meaningful contribution it had made to the field over the past seven years. Not only had the HBP not reverse-engineered a human brain, it had seemingly not achieved very much at all.

One of the biggest steps we’ve taken toward emulating the human brain so far has been to simulate the neural connectome of another species: the roundworm. As Dr Scott Emmons told The New York Times in 2019, “It’s a major step toward understanding how neurons interact with each other to give rise to different behaviours.” As Avinash Singh described it to me, in observing the simulated roundworm, you start to see it “search for food and behave like a worm, which are not programmed behaviours. This gives us hope that maybe it’s possible with the human brain.”

Important to keep in mind, though, is the fact that the roundworm is one of the simplest organisms on the planet. It’s about the size of a comma and has a total of approximately 330 neurons. While figuring out an organism that simple might sound pretty straightforward, it took the team working on the project roughly nine years to simulate those neurons and the synapses that join them together – to form what is known as a connectome. Even then, as one scientist put it, “It doesn’t tell you what the neurons are saying to each other or when, whether they change with age or what the extent of variation between individuals is.”

To put all of that into some kind of perspective, the human brain has billions of neurons and trillions of synapses, plus a whole other slew of things called axons and dendrites that may or may not affect brain function. It has frequently been described as the most complex organism in the known universe.

Mind uploading advocates like Kurzweil and Peter Xing would argue that all of this will essentially work itself out as the law of accelerating returns really starts to kick into gear. In other words the magnitude of technological steps, and the pace at which those steps are taken across multiple fields, will speed up to such a degree as to bridge what seems, from today’s standpoint, to be unbridgeable gaps. Xing likes to think of it as taking the broad view. “I can see where they’re (the sceptics) coming from,” he says.

“If I was to work in that specialty and all the other papers I’ve read in the field show we’re nowhere close, then yeah, definitely I understand. But I’d recommend for them to essentially work with more people outside their field in those areas of nano-tech, or machine learning – areas where that convergence of tech will be. That’ll expand their horizon of the art of the possible within physics. And I think if we get more people to work across those verticals, that’s where the real innovation will be. If they’re stuck in that particular local minimum, we really want to accelerate by bringing in these other fields.”

(Photo: Harvard Brainbow Laboratories)

Running underneath this idea that scientists will be able to understand the brain once exponential growth catches up to its raw computing capacity, is the inherent assumption that the brain ‘computes’ in ways we can conceivably comprehend. Dr Stuart Hammeroff from the University of Arizona has long believed this concept to be deeply flawed. He argues instead that “consciousness is more than computation. Consciousness is something deeper, more profound, connected to the quantum structure of the universe. It bridges between science and spirituality, and I think actually will blur that distinction if it turns out to be true, which I think it will.”

If we’re going to reverse-engineer the brain, Hammeroff argues, we’ll need fundamentally different methods than those currently on the table. “Assuming that a neuron is a ‘bit’ firing on and off is an insult to the neuron.” In Hammeroff’s view, then, the so-called neurons produced by a company like Neuralink really have little-to-no bearing on our real neurons; replacing our real ones with these synthetic ones would be like replacing a car’s chassis with a baby-grand piano.

Australian-British biochemist Michael Denton doesn’t quite go down the same quasi-spiritual route as Hammeroff, but he does argue “there remains a very real possibility, I would say a near certainty, that elusive, subtle, irreducible vital differences exist between the two categories of the ‘organic’ and the ‘mechanical’.” In Denton’s view, understanding the brain will ultimately have little or nothing to do with exponential increases in computing power, because brain function doesn’t even remotely resemble any form of classic computation we know of.

“My prediction,” he writes, “is that Kurzweil’s ‘spiritual machines’ (computers with the capacity of the human brain in terms of hardware) will be wonderfully fast calculators but will still not possess the unique characteristics of the human brain, the ability for conscious rational self-reflection.”

It’s a conclusion that gels pretty well with Gary Marcus’ assertion that we don’t even know what kind of computer the brain is yet, much less how to approach emulating it. Similarly, Paul Allen writes that while a fine-grained understanding of the brain might one day be possible, “it has not shown itself to be the kind of area in which we can make exponentially accelerating progress.”

“[‘Spiritual machines’] will still not possess the unique characteristics of the human brain, the ability for conscious rational self-reflection.”

One thing that has occurred to me again and again in looking at mind uploading, is that many of its biggest backers seem to have a pretty profound fear of death. As Ernest Becker argued a long time ago in his Pulitzer Prize-winning The Denial of Death (1973), all of us are basically scared to death of dying – claims that have been pretty robustly backed up in the more recent The Worm at the Core (2015) by Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenburg, and Tom Pyszczynski. In the cases of Ray Kurzweil and Peter Xing, though, death aversion seems even more pronounced than usual.

In a recent appearance via satellite at the World Knowledge Forum 2020, the long-since follicly challenged Kurzweil bizarrely wore a lustrous, bright orange wig that might best be described as ‘the Eric Stoltz circa 1993’s Foreign Affairs.’ Then there are the hundred-plus supplement pills he takes every day, with the express intent of ensuring longevity.

At just 36, the much younger Peter Xing (Kurzweil is 73) has long insisted that ageing should be counted as a degenerative disease, much like Alzheimer’s, and not a fact of life. “My thoughts are still consistent with that,” he says. “If we look at it from an engineering perspective, then yeah, it needs to be [considered] a disease because then bodies like the FDA will be able to approve the medicines and research that will help fund big pharma and find a way to treat it.” Open on Xing’s computer when we spoke was a Google Chrome extension that reminds him how long he has left to live, based on averages. “I’ve got about 16,000 days left,” he says. He checks it every single day.

It raises the question of whether their shared faith in the prospects of mind uploading really just comes down to an intense desire not to die. Put another way, does it all just boil down to emotion instead of cold scientific objectivity?

Kurzweil predicts the singularity will arrive in the year 2045, at which point he’ll be 97 years old, providing of course that he’s still alive. One could look at that as a pretty convenient coalescence between his own expiration date – if he’s feeling optimistic – and the arrival of a digital immortality option.

“I think it’s a valid point,” says Dr Avinash Singh to the question of whether a fear of death might be warping the perspectives of those who believe in mind uploading. “I think that’s happening a lot with older people in this field in particular. Their motivation seems to be to save themselves, as well as everyone else.” In terms of young people in the field too, Dr Singh knows many who he says, “are really, really fearful of death.”

For Singh, however, this doesn’t tell the full story. For one thing, he’s not scared of death – or at least not consciously so. This lack of fear comes down, Singh says, to his Hindi upbringing where death was associated with reincarnation and treated as an important part of the lifecycle. “Whether I like to believe in it or not now, my [upbringing] still deeply affects me.”

And yet, he remains relatively confident that mind uploading could be on the horizon. If belief in the cause is tied intrinsically to a fear of death, then how could someone who doesn’t fear it still be a believer? It’s because, Singh says, the science behind this idea is real and valid. It might sound like another immortality sham, “but it’s not just a sci-fi concept. There’s quite a possibility we will see it. The only limitation we have is the hardware.”

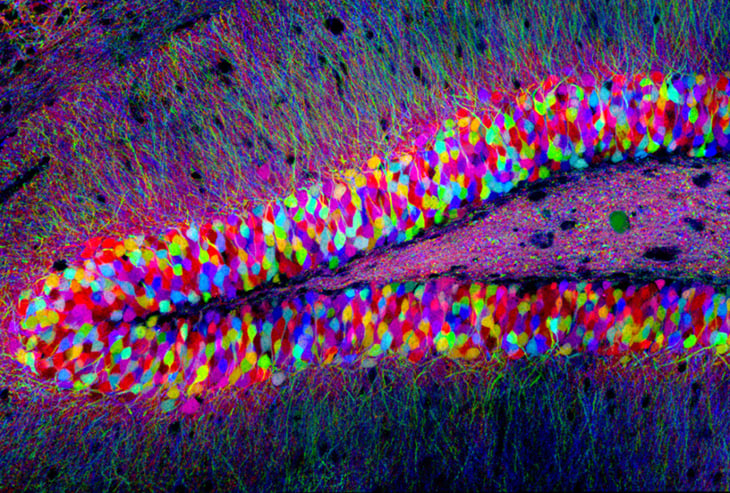

This image traces the pathways of nerve impulses in a mouse. (Photo: Harvard Brainbow Laboratories)

Whether or not you’re convinced that mind uploading and digital immortality are coming down the pike, the work toward these ends continues at high speed. And maybe it’s that work alone – and the breakthroughs that come from it – that ultimately justifies the whole endeavour, whether it ends up reaching into Promethean territory or not.

Europe’s HBP has been pretty extensively written off as an abject failure and a waste of taxpayer money. Some of the people I spoke to, however, see it differently. Although it fell absurdly short of achieving its initial aims, according to Matthew Kiernan the HBP achieved other important outcomes. “It helped to create international networks, so that now we’re very much connected worldwide.” Neuroscientists are now collaborating across disciplines in ways they never have before, and a lot of that, Kiernan suggests, was sparked by initiatives like the HBP.

In trying to crack the brain, scientists have developed game-changing, and in some instances, life-saving technologies such as Neuralink, Stentrode, Teslasuit, and many, many more – let’s not forget the work on dog dementia, obviously. “You never know what you’re going to find out along the way,” as Matthew Kiernan put it to me.

That might be the main point here: The outcomes scientists are achieving along the road toward mind uploading seem to make the whole pursuit pretty darn worthwhile, whether we make it to the promised land or not. Or to put it in those all too road-worn and tinkered-with words of Ralph Waldo Emerson – which you’re probably most likely to see these days overlaid onto a picture of a neon sunset falling across an endless ocean – it’s not the destination that counts, it’s the journey.