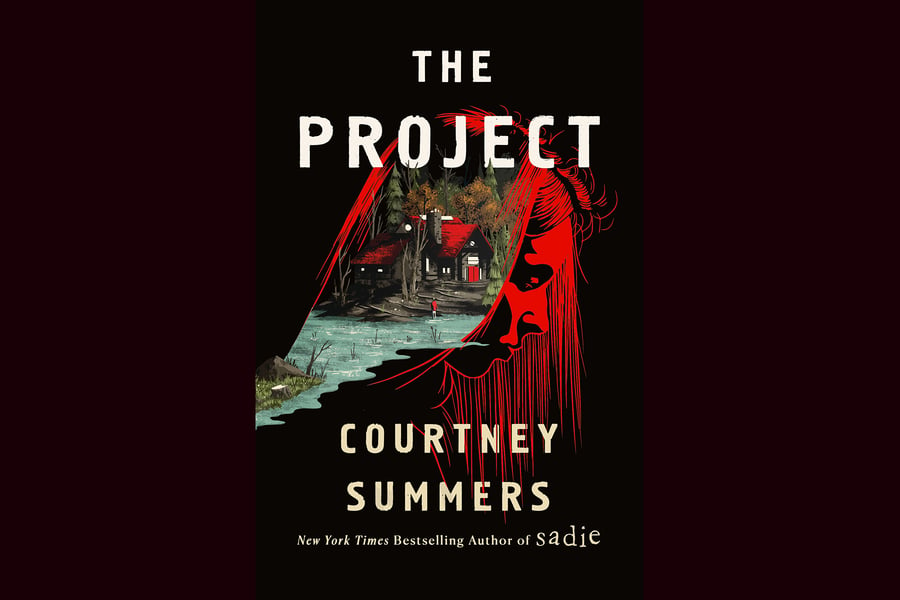

Author Courtney Summers wants to destroy you. Not literally, of course, but through the devastating young-adult books she’s spent the last decade writing. Her latest, The Project, is no different. A harrowing look at cults and the people who fall prey to them, Summers’ ninth book hits shelves on February 2nd via St. Martin’s Press.

The Project centers on sisters Lo, 19, and 20-something Bea Denham following the death of their parents and Bea’s entrance into a cult called the Unity Project. After Bea cuts off all contact with Lo, the younger woman becomes anxious about her sister’s whereabouts — it doesn’t help when a man comes to the magazine where she works as an assistant and claims that the Unity Project killed his son. Despite being pretty low on the magazine’s masthead, Lo uses its clout to investigate the Project’s charismatic leader, Lev Warren, and — in doing so — find Bea. What follows is a fascinating look at cults, who joins them, and why.

Summer’s last book — the New York Times bestselling Sadie — came out in 2018 to much acclaim; a dual point-of-view novel, it follows 19-year-old runaway Sadie as she flees the brutal murder of her sister Mattie, and podcaster West McCray, who is investigating Sadie’s disappearance. Both are currently available to read online through Amazon Kindle, or as an audiobook via Audible.

Rolling Stone spoke with Summers, 35, about cults, why she could see herself joining one, and just why she found inspiration in Jim Jones.

So why did you decide to write a book about cults?

After Sadie came out, I was trying so hard to figure out what the next book would be. And I kind of had this feeling that I wanted it to be about a cult because I was thinking about how nobody thinks that they’d join a cult. They feel that they’d be impervious to that kind of influence that they’d never be so foolish as the follow after one person and just lose themselves entirely. Then I was thinking, “Am I that kind of person?” I feel like I would join a cult.

I feel like the overall vibe for most people is that they’re resistant to that idea. And I kind of think it’s one that lacks empathy. You have to really remove a lot of context from what it is that gets people into those situations to support the thesis that you’d be above making the same kind of decisions.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

I was like, “I want to write a book that pushes at that.” But when I brought it up to my editor, I was like, “You have to talk me out of this because when you sit down to write a cult novel, there’s only one way they can go, right?” So, it’s like, “Oh, this is going to be a lot of work.” Like how to keep it suspenseful, how to keep it tight, how to make sure the emotions are at the forefront and it’s emotionally alive because cult novels kind of give themselves away every time. So, it was this is a huge undertaking. I told her, “Please talk me out of it.” And she didn’t.

Why do you think you’d join a cult, exactly?

I know the power of community and connections — those I’m a part of and those I’ve made. I’m not shy about admitting that I’m a vulnerable person. I think I have to be to tap into the part of me that wants to write about these things. I have to allow myself to be vulnerable, to be empathetic, to bring those kinds of emotions to the forefront of my process. But knowing that about myself, it’s also knowing that these are very easy exploitable traits for a person to have. I just figure, you know, if I came across the right cult leader at the right time, I might have a problem saying no. I really hope that’s not the case, but I’m going to be honest with myself.

What kind of research did you do on cults?

I started out really broadly. I was just getting a sense of, what is a cult? What makes the cult, who joined the cult? And then I stumbled upon Peoples Temple and Jim Jones. And I was like, “This is it. This is what I need to build The Project around because there’s such an interesting case study.” The Peoples Temple was deep into Civil Rights Movement. And they believed in helping people. They wanted everyone clothed, sheltered, and fed. They wanted everyone to have healthcare. They just really looked after their community. And their objective was perverted by one man, one madman. And you could really see Jim Jones trying to appeal to people’s better nature, which felt unique to me. At the start, it wasn’t an apocalyptic approach. It was, “We can make the world a better place.” And I thought that was just so tragic and heartbreaking.

Author Courtney Summers (Photo: Megan Gunter*)

Your brand on social media is basically, “This book will destroy you.” Let’s talk about that. Do you feel pressure to make each book more distressing than the last?

It’s my brand really, like, taken to the next level. And now it’s like a part of The Project’s marketing: “Courtney Summers will destroy you.” I mean, there’s going to be a certain level of pressure with every release, following Sadie. It was certainly a little intense because that was my sixth book, but it was the one that happened to break out. And everyone talks about how upset that made them, but I’ve been upsetting people for over a decade. I love to really push it. I never want to leave a reader happy. I just want them to be upset. I’m never going to totally succeed in my goal all the time. But if I’m satisfied with the end product, I know I’m going to have upset someone. I feel pressure to ruin people’s lives, but I rise to meet the occasion every time I like to think.

There’s a lot of pressure in YA fiction to inspire, to leave readers feeling motivated. Why do you want to “ruin people’s lives”?

Something that I’m consistently exploring in my work is violence against women and the way we fall short with victims and survivors. I wouldn’t say I’m inspired by that, but I’m really outraged. And my books are a response to the anger I feel about certain issues — I want them to serve as a confrontation of those issues. So, I really want readers to finish my books feeling similarly outraged and going, “OK, if this is how the world is, how do I change it?”

I actually think that my inclination toward dark stories is, as weird as this sounds, a reflection of optimism. Because as grim as they are, as hopeless as they sometimes might feel, I see them as a love letter to our ability as people to endure and emerge from our darkest moments to find something meaningful on the other side.

From Rolling Stone US