As COVID-19 gathered casualties across Australia, Byron’s housing crisis reached a tipping point. This is the story of Byron Bay's “unseen homeless”.

Hundreds, if not thousands, of people are living in their cars because there is nowhere else. They roam the highways at night looking for a safe spot to pull over for a few hours sleep. One couple gets lucky and finds an old abandoned bus to lay up in. Others are parking and sleeping on the sides of hills from where they can see enforcement officers coming before it’s too late. Others are setting up makeshift encampments in bushland or over behind the sand dunes where they hope not to be noticed. All too often these desperate people are either stranded retirees, or young single mothers with one or two kids under their care.

Where do you think this is happening? East Sudan? Syria? The Polish-Belarusian border? While one can be certain that all of the above and much worse is happening in such well-known epicentres of tragedy, it’s not what I’m talking about here. Far, far from it.

Welcome to Byron Bay. Australia’s ultimate hype village in New South Wales where upwards of two million tourists arrive every year to experience the warm climate, the beaches as picturesque as any Brett Whiteley brush stroke, and what has become an iconically laid-back lifestyle couched in countercultural aesthetics and values. In the past, newcomers would usually go home after the high-seasons or music festivals were over. The place would then fall back into the hands of its roughly 35,000 permanent residents for a few quiet months. But nowadays… not so much.

Last year, COVID-19 triggered a mass exodus from the big cities in favour of small towns and remote work. This phenomenon has affected Byron Shire perhaps more than any other region in Australia. There’s its growing community of A-list celebrities—Damon, DiCaprio, a buffet of Hemsworths—and influencers whom we hear so much about. Then there are the other less prominent, but hardly less affluent types who have moved up in droves from Sydney and Melbourne since the beginning of the pandemic. Property prices have skyrocketed as a result of this influx. A two bedroom house in Byron will now cost you about as much as one in the eastern suburbs of Sydney.

This is the prevailing image of Byron in the early 2020s: one of laid-back luxury in the extreme. Beautiful tan bodies laying posed on glittering beaches. Others out walking the quaint streets in flowing linens, furtively swiping black Amex cards while they’re at it. What such an image fails to capture, however, is the crisis unfolding just beneath the surface and beyond the social media framelines.

Surges in popularity and demand for housing have in fact placed immense pressure on much of the pre-existing community in Byron Shire. Those who rent have faced average rental increases of approximately 34% over the last 12 months, and there is no sign these increases are about to let up. Then there are the many locals who have been displaced by landlords who decided they can make more money by permanently listing a property on a short-term rental platform such as Airbnb.

The locals who have been forced out of their homes, either by rent hikes or the short-term rental market, are often finding themselves with nowhere to go. Where the statewide housing vacancy average hovers around 3.9%, in Byron Shire only 0.3% of residential real estate stands unoccupied. There is basically no social housing to speak of in the area, nor are there any temporary accommodation or crisis accommodation options, as Ianna Murray, a caseworker from the Byron Bay Community Centre, told me. The one and only (somewhat) nearby shelter, which is an hour away in Tweed Heads, has been deemed by evaluators as “grossly inappropriate” for anyone to be housed in.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

All of these conditions have essentially coalesced to create a burgeoning homelessness crisis in Byron Bay. There are more documented homeless in Byron right now than anywhere else in the state, excluding Sydney. Even then, as the head of Byron Council’s rough sleeping initiative, Celeste Harris, says, the numbers of rough sleepers in Sydney are actually decreasing, “whereas in Byron they are going up”. “The trends are not great,” says Harris.

The most recent street count by NSW’s Department of Communities and Justice estimates there are 198 people sleeping rough in Byron Shire. That might not sound like a lot, but what street counts such as this typically fail to recognise is the number of displaced peoples living in a given area. In other words, those who might not identify as homeless but are nonetheless living without a stable address. Instead of their own residence, these people typically sleep in cars, vans, or tents, or on friends’ couches. Another way to think of them, says Shannon Burt from local council, is as the “unseen homeless”.

Of course, firm numbers of unseen homeless in Byron Bay are difficult to come by. But no one has any doubt there are a lot of them around. “There is a huge data gap,” says Burt. “We know what we know from the street counts, but then there’s this whole other group of displaced people. I do know from my officers going out that there is an increasing number of people presently congregating in various parts of our Shire just because they’re stuck with nowhere to go.”

Sama Balson, who runs a local community organisation called the Women’s Village Collective (WVC), estimates there could be upwards of 2,000 women currently living in insecure and unseen circumstances in and around Byron. “I’m seeing so much of it,” says Balson. “We’re not talking about people who have addiction issues here, and we’re not talking about people who aren’t employed. We’re talking about nurses, pre-school teachers—these are the people I’m seeing. Key workers in the lower income brackets who have been forced out of their homes by skyrocketing prices.”

Balson has been working with one young woman who has two degrees, works full time for a local company, and has a daughter in one of the local schools. “They have been homeless for the past five and a half months, sleeping in their car,” says Balson. WVC has managed to find housing for this mother and daughter in the Shire in recent weeks, but they are among the lucky few to be extended a helping hand. In one 24-hour period not long ago, Balson received calls from seven different mothers facing eviction due to untenable hikes in rent. “They had nowhere to go and three weeks to find a place,” she says.

Similarly tragic stories keep piling up in Byron at the moment.

In the week prior to our conversation, Ianna Murray from the community centre had been working with one woman facing eviction from the local campground where she has lived for the past two years. “This is a 44-year-old woman who’s currently undergoing treatment for cancer, she’s just about to go back for her second round of chemo, and she was just given a letter from the campground people saying she had to be out immediately,” says Murray. Staying in a campground for more than 28 days is technically prohibited in Byron. Until recently, though, the campground owners had looked the other way in this case (which happens a lot, so I was told) because the tenant had always paid her rent on time using money she made from her work as a cleaner. “Never missed a payment,” says Murray. But now that she has been evicted she has very few options other than to sleep in her vehicle while juggling chemo and a job.

“I did manage to book her a couple of nights at a place that will bring her up to next week,” an exhausted and frazzled-sounding Murray told me. In the meantime, Murray was intending to try to find this woman a more permanent living solution. As to the question of what would happen if she was unable to do so, Murray lamented, “Well, this is just the reality we’re faced with. We can only do so much. I’m super transparent with the people that we support about the current climate. We can only do so much, and I have to accept that so I can sleep at night.”

“In the past, homeless people were usually those who had severe and complex needs. Now it’s my friends.”

To reiterate, many of the people who are currently facing homelessness in Byron Shire have jobs. Often they are full-time employees. Or as Celeste Harris explains, “in the past, homeless people were usually those who had severe and complex needs. Now it’s my friends.” Of course, that is not to say those who do have severe and complex needs should be overlooked. It does, however, make this issue seem all that much more stark and close to the bone. As Jean Renouf, co-founder of not-for-profit Resilient Byron told me, the fact that so many of the homeless now have jobs “makes the old Australian adage of a ‘fair go’ seem like nothing but empty words”.

In addition to affecting working people, the current crisis also seems to be disproportionately affecting women in Byron. Unfurling exactly why that’s the case would require deep research beyond the scope of this article, but Balson does have some thoughts. For one, she says, “women are on average retiring with 47% less superannuation than men, and as a result a lot of elderly single women are faced with housing insecurity later in life.”

Balson has also seen several instances where single mothers have been court-ordered to stay within a 50-kilometre radius of an ex-partner who lives in the area, even if that ex-partner is paying zero in child support and offering no other help in terms of co-parenting. “So all the burden is falling on the mother in these cases, and she’s often finding herself trapped in insecure housing as a result,” says Balson. In Balson’s view, the gender-biassed nature of the crisis is just further evidence of inequalities that have long been baked into an Australian system that treats women—in particular single women and single mothers—as second-rate citizens worthy of little acknowledgement or support.

Despite best efforts to stay hidden, Byron’s to-date largely unseen homeless population has inevitably started to spill over into the public eye. “We’re receiving a lot of complaints lately from community [residents] who have just moved in, and suddenly they are seeing people across the street camped in a van, or people in the bush, and they don’t like what they see,” says Shannon Burt. “Before COVID you wouldn’t see it so much,” says Renouf. “But now it’s become such an obvious crisis that you just can’t ignore it.”

The question becomes, what can be done to stop the already spiralling situation from getting worse?

Countercultural roots run deep in Byron Bay and its surrounds. It’s not just an image; real hippies and social justice warriors do exist here in numbers and have done so for a long time. This is the community that banded together to keep out corporate giants like McDonald’s and Club Med. For months on end they came together to form the Bentley blockade, ultimately putting a stop to fracking in the region before it could begin. A series of progressive councils, working alongside highly motivated community organisers, have successfully managed to keep Byron from turning into another Surfers Paradise, with its gaudy skyline and rampant over-commercialisation. Now those same groups are banding together again to fight back against homelessness in an attempt to keep some semblance of their historically diverse, eclectic, and balanced community intact.

MANDY NOLAN SPEAKING AT THE ‘NUDE AIN’T RUDE’ RALLY IN 1997. Photograph by John McCormick

Help is coming from almost all directions. There is the aforementioned Sama Balson and WVC. There are the likes of Ianna Murray and Kate Love at the community centre, Shannon Burt and Celeste Harris at local council. There is the prominent local comedian, writer, and now, Greens politician, Mandy Nolan, who is trying to bring attention and political action to the issue. There are the many local NGOs, including Resilient Byron which works to “build the resilience and regenerative capacities of the residents”; and Orange Sky which provides both shower and laundry facilities to the local homeless community.

Even some local property developers have stepped up. Brandon Saul, a self-described “accidental property developer” and co-founder of some of the region’s biggest music festivals, including Splendour in the Grass, has put up money to fund local shower and breakfast programmes. He has also been one of the key backers of a newly opened “homeless hub” called Fletcher Street Cottage—which is linked to the local community centre. The goal of Fletcher Street, says Saul, is to “provide wraparound services for homeless people and those in danger of becoming homeless: everything from arranging doctor and accountant appointments, to helping people to locate housing”.

In the first month of the fundraising campaign for Fletcher Street, the project raised over $400,000. “And that was right when the lockdown started too,” says Saul. “We had everyone from a previously homeless person giving $10 per week, up to Chris Hemsworth giving $125,000 for Fletcher Street,” says Kate Love from the community centre. “It goes to show,” adds Saul, “that the underbelly of Byron’s community is good with a capital G”.

Still, the words of Ianna Murray carry weight: “We can only do so much.” It’s true. The community itself cannot be expected to fix this problem on its own. They need state and federal governments to step in and provide support. “Without government support,” Saul told me, “we are really only talking about band-aid solutions here.”

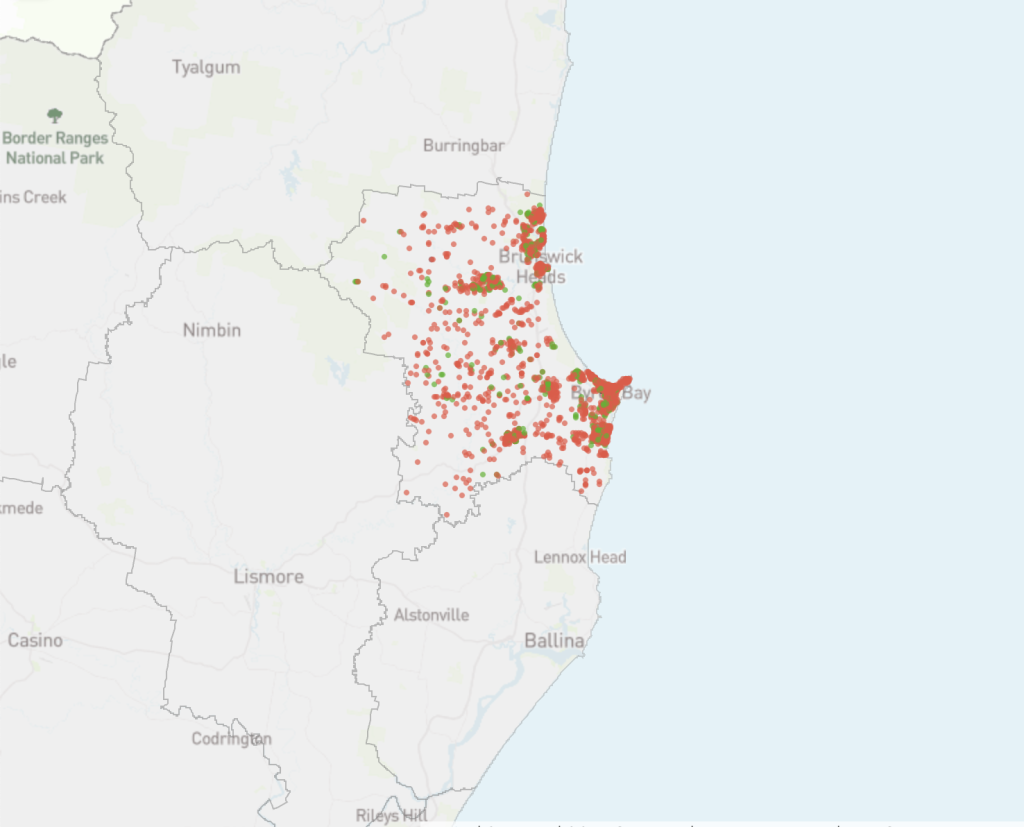

THE “INSIDE AIRBNB” MAP OF BYRON SHIRE.

Of the roughly 13,000 properties in Byron Shire, around

3,500 are listed permanently on Airbnb.

First and foremost, says Mandy Nolan, “we need policy that strictly limits Airbnb and other short-term rental providers in the area”. Of the roughly 13,000 properties in Byron Shire, around 3,500 are listed permanently on Airbnb at the moment. Saul showed me a satellite map called “inside Airbnb” which indicates these short-term properties using red dots. The dots are so densely clustered in Byron that it looks like the area has some sort of malignant rash. “That’s the real epidemic right there,” says Saul. Theoretically at least, placing strict limitations on short-term rental letting would free up some, if not most, of those 3,500 Airbnb properties for permanent tenants again, in turn alleviating a good deal of the pressure in the housing market. “If we don’t have policy to manage Airbnb, we’re screwed,” says Saul.

So far, the state government has not come to the table on this issue. Local council went to state legislators in recent months and offered to retain Airbnb in certain areas (the tourist-centric area of Wategos Beach, for example) for 365 days per year. In exchange, they wanted it banned in other predominantly residential neighbourhoods in order to keep them exclusively residential. State government rejected that proposal. Council then went back and requested Airbnb be limited to 90 days per year in those neighbourhoods. That proposal has also been rejected in recent weeks. According to the council, it’s looking like a 180-day-per-year plan might be accepted. But, as Saul says: “If they’re still getting $2,000 per night for 180 days per year, landlords will remain incentivised to leave the properties on Airbnb. That could work out even worse, with properties then sitting literally empty for half the year.”

It’s not just the Airbnb issue that state legislators are refusing to engage on. State government has also refused to implement a “bed tax”, which would essentially tax short-term rental users and other visitors, in turn providing some much needed revenue to local council. Legislators have also ignored petitions for the abolition of “no cause” evictions, whereby landlords are able to evict tenants with “no cause” by simply providing 90 days written notice. There are no plans to develop any community housing or crisis accommodation options in the area. Local council has managed to cobble together its own funding for a few full-time public liaison officers, who are charged with going out into the community and interfacing with rough sleepers about their needs, but no personnel funding has been provided by state or federal governments to help manage the issue. “There is definitely a disconnect between funding provisions and need in the community,” says Celeste Harris. “The dire stats in Byron are clear, but state government is still not acting.”

“The frustration I have every day,” says Shannon Burt at the local council, “is that I come here and I advocate for certain types of changes to planning controls and other types of support on this issue, and I get crickets from state, or I get resistance because it’s not neat. I then have to go back to those people who are crying for help and say, ‘I’m sorry, just a little bit longer’.”

State and federal governments seem to be telling Byron that it’s on its own. According to Mandy Nolan, that’s exactly what’s happening. “Neither of the major parties is willing to get in the way of investment or throw business under the bus in any way, but they’ll throw people, community, the vulnerable, under it no problem,” says Nolan.

The reality is that without real systemic change and government support, the crisis only looks set to get worse. “We are trying to hold the space,” says Kate Love at the community centre. “But it’s not sustainable in the long run for us to hold this together on our own.”

It’s not just Byron facing housing shortages, widening equality gaps, and increasing homelessness. Rather, Byron is something of an overheated test case for a much deeper issue that is gradually spreading its way across the state and the country at large. Recent data from the Community Housing Industry Association NSW shows the state currently has a shortage of at least 70,000 social housing dwellings. With growing demand and drastic shortfalls in supply, it only makes sense that those already facing financial strain will continue to be squeezed toward breaking point. Numbers of homeless, either seen or unseen, seem almost destined to increase as a result.

I currently live in America. Generally speaking, the US has long been on the warpath against the public sector. Public housing and social services have been grossly underfunded for years, not to mention public health and education. The prevailing thinking has been that deregulated markets would effectively regulate themselves and provide for everyone in turn, thereby bolstering the rich and poor alike. There would therefore be no need to spend on public programmes. We all know by now that this idea hasn’t really worked out. Instead the rich are now mega rich, while the formerly working class have largely found themselves in dire straits with virtually no social safety net to fall back on. Many have consequently fallen into homelessness.

I recently visited Portland, Oregon, where it’s impossible not to notice the vast population of homeless living in tent cities that line the streets of the downtown area. Scratch the surface in any major American city and you are likely to find a similar scenario—thousands of desperate people camped out in plain sight. Every night, more than 500,000 Americans experience homelessness. I for one would hate to see the cities and towns in my own country go this same way. But based on the current trajectory of things in Byron and elsewhere—coupled with government’s continued insistence on the American approach to policy making at the expense of the public—it’s very difficult to see it going any other way.

This article features in the March 2022 issue of Rolling Stone Australia. If you’re eager to get your hands on it, then now is the time to sign up for a subscription.

Whether you’re a fan of music, you’re a supporter of the local music scene, or you enjoy the thrill of print and long form journalism, then Rolling Stone Australia is exactly what you need. Click the link below for more information regarding a magazine subscription.