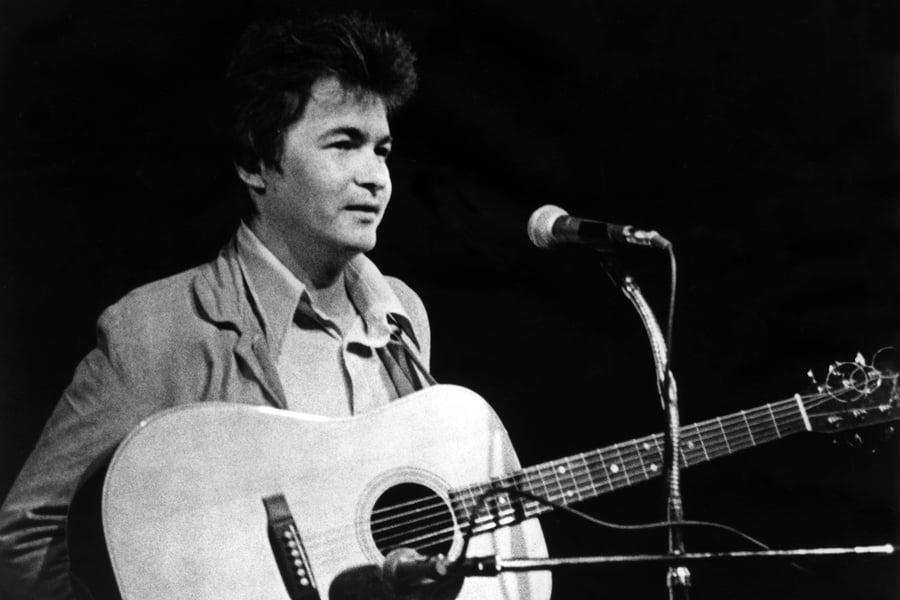

John Prine, who for five decades wrote rich, plain-spoken songs that chronicled the struggles and stories of everyday working people and changed the face of modern American roots music, died Tuesday at Nashville’s Vanderbilt University Medical Center. He was 73. The cause was complications related to COVID-19, his family confirmed to Rolling Stone.

Prine, who left behind an extraordinary body of folk-country classics, was hospitalized last month after the sudden onset of COVID-19 symptoms, and was placed in intensive care for 13 days. Prine’s wife and manager, Fiona, announced on March 17th that she had tested positive for the virus after they had returned from a European tour.

As a songwriter, Prine was admired by Bob Dylan, Kris Kristofferson, and others, known for his ability to mine seemingly ordinary experiences — he wrote many of his classics as a mailman in Maywood, Illinois — for revelatory songs that covered the full spectrum of the human experience. There’s “Hello in There,” about the devastating loneliness of an elderly couple; “Sam Stone,” a portrait of a drug-addicted Vietnam soldier suffering from PTSD; and “Paradise,” an ode to his parents’ strip-mined hometown of Paradise, Kentucky, which became an environmental anthem. Prine tackled these subjects with empathy and humor, with an eye for “the in-between spaces,” the moments people don’t talk about, he told Rolling Stone in 2017. “Prine’s stuff is pure Proustian existentialism,” Dylan said in 2009. “Midwestern mind-trips to the nth degree.”

Prine was also an author, actor, record-label owner, two-time Grammy winner, a member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame, the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, and the recipient of the 2016 PEN New England Song Lyrics of Literary Excellence Award, a honor previously given to Leonard Cohen and Chuck Berry. Prine helped shape the Americana genre that has gained popularity in recent years, with the success of Prine fans such as Jason Isbell, Amanda Shires, Brandi Carilie, to name a few. His music was covered by Bonnie Raitt (who popularized “Angel From Montgomery,” his soulful ballad about a woman stuck in a hopeless marriage), George Strait, Carly Simon, Johnny Cash, Don Williams, Maura O’Connell, the Everly Brothers, Joan Baez, Todd Snider, Carl Perkins, Bette Midler, Gail Davies, and dozens of others.

Though he was an underground singer-songwriter for most of his career, Prine had a remarkable final act. In 2018, he released The Tree of Forgiveness, his first album of original material in 13 years. The album went to Number Five on the Billboard 200, the highest debut of his career, and he played some of his biggest shows ever, including a sold-out tour kickoff at New York’s Radio City Music Hall. The album was released on Oh Boy Records, the independent label Prine started with his longtime manager, business partner, and friend Al Bunetta. In recent years, Prine, his wife, and son Jody ran the label out of a small Nashville home office.

Prine’s string of acclaimed solo albums began with his self-titled 1971 debut on Atlantic Records, featuring a tracklist that reads like a greatest-hits compilation: “Illegal Smile,” “Spanish Pipedream,” “Hello in There,” “Sam Stone,” “Paradise,” “Donald and Lydia,” “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You Into Heaven Anymore,” and “Angel From Montgomery” among them. Throughout his career, Prine explored a wide variety of musical styles, from hard country to rockabilly to bluegrass; he liked to say that he tried to live in a space somewhere between his heroes Johnny Cash and Dylan.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Prine was born in the Chicago suburb of Maywood, Illinois. His father was a tool and die maker and the president of the local steelworkers union, and raised John and his three brothers on the music of Jimmie Rodgers, the Carter Family, Hank Williams, and other heroes of Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry. Though he was a poor student, Prine was a natural songwriter; two songs he wrote when he was 14, “Sour Grapes” and “The Frying Pan,” ended up on his LP Diamonds in the Rough, more than 10 years later. Prine had a restless imagination — “I would go to class and just stare at something like a button on the teacher’s shirt,” he said — but he excelled at hobbies he focused on, like gymnastics, which he was inspired to take up by his older brother, Doug. “Here was something I had no natural ability in, and I could do it well,” Prine said.

After graduating high school in 1964, Prine took the advice of his oldest brother, Dave, and became a mailman. Wandering around the Chicago suburbs, Prine wrote many of his classic early songs. During his postman years, he wrote “Donald and Lydia,” about a couple who “make love from 10 miles away,” and “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You Into Heaven Anymore,” a humorous indictment of misguided patriotism, after he noticed that locals were posting American flag decals that were included in an issue of Reader’s Digest around the neighborhood.

Prine was forced to take a hiatus from his postal career when he was drafted into the Army in late 1966, just as the Vietnam War was heating up. But instead of being sent to Vietnam, Prine lucked out and was sent to Stuttgart, West Germany, where he worked as a mechanical engineer. Prine played down his military service, describing his contribution as “drinking beer and pretending to fix trucks,” as he told Rolling Stone. But the experience did bring him to write maybe his greatest song: “Sam Stone.” The ballad is about a soldier who comes home from the war mentally shattered, turning to morphine to ease the pain. “There’s a hole in daddy’s arm where all the money goes,” Prine sings in the chorus, “Jesus Christ died for nothin’, I suppose.”

“I was trying to say something about our soldiers who’d go over to Vietnam, killing people and not knowing why you were there,” Prine told Rolling Stone in 2018. “And then a lot of soldiers came home and got hooked on drugs and never could get off of it. I was just trying to think of something as hopeless as that. My mind went right to ‘Jesus Christ died for nothin’, I suppose.’ I said, ‘That’s pretty hopeless.’ ” When Johnny Cash covered the song, he rewrote the chorus, changing “Jesus Christ died for nothin’, I suppose,” to “Daddy must have hurt a lot back then, I suppose.” (“If it hadn’t have been Johnny Cash,” Prine said, “I would’ve said, ‘Are you nuts?’”)

Prine became an immediate sensation on the Chicago folk scene. On the day before his 24th birthday, he was performing at Chicago’s Fifth Peg when the now-iconic Chicago Sun-Times film critic Roger Ebert walked in. Ebert’s headline, ‘Singing Mailman Delivers a Powerful Message in a Few Words,’ led to sold-out rooms. Soon, Prine’s friend and musical partner Steve Goodman convinced Kris Kristofferson and Paul Anka to drop by to see Prine play at the Earl of Old Town in the summer of 1971.

“It was too damned late, and we had an early wake-up ahead of us, and by the time we got there, Old Town was nothing but empty streets and dark windows,” Kristofferson later wrote in the liner notes for Prine’s first album. “And the club was closing. But the owner let us come in, pulled some chairs off a couple of tables, and John unpacked his guitar and got back up to sing. … By the end of the first line we knew we were hearing something else. It must’ve been like stumbling onto Dylan when he first busted onto the Village scene.”

Kristofferson invited Prine onstage at New York’s legendary Bottom Line. The next day, Atlantic Records President Jerry Wexler offered Prine a $25,000 deal with the label. With Anka serving as his manager, Prine cut the majority of his self-titled album at American Sound in Memphis, with the studio’s house band, the Memphis Boys, famed for their work with Elvis Presley, Dusty Springfield, Bobby Womack, and others. Though Prine lamented how nervous he sounded on the recording, and it did not make a major dent on the charts, it is now considered a classic, a touchstone for everyone from Bonnie Raitt to Steve Earle to Sturgill Simpson. In January 1973, Prine was nominated for a Grammy as Best New Artist, and Bette Midler included “Hello in There” on her debut LP, The Divine Miss M. Midler recently called Prine “one of the loveliest people I was ever lucky enough to know. He is a genius and a huge soul.”

“He was incredibly endearing and witty,” Raitt told Rolling Stone in 2016. She met Prine in the early Seventies and first covered “Angel From Montgomery” in 1974. “The combination of being that tender and that wise and that astute, mixed with his homespun sense of humor — it was probably the closest thing for those of us that didn’t get the blessing of seeing Mark Twain in person.”

While Prine may have been signed to Atlantic Records, he did not conform to pop music’s rules. His follow-up to his self-titled album, 1972’s Diamonds in the Rough, was a stripped-down acoustic album that paid homage to his Appalachian bluegrass roots, which he recorded with his brother Dave for around “$7,200 including beer.” Prine likened the major-label system to a bank “for high-finance loans. You could go to a bank and do the same thing for less money and put a loan behind your career instead of a major label throwing parties for you and charging you, and giving you the ticket and not asking what you want to eat.”

Feeling that the label could have done more to promote the hard-edged 1975 album Common Sense, he asked co-founder Ahmet Ertegun to let him out of his contract. Ertegun agreed, and Prine moved to David Geffen’s smaller Asylum label for 1978’s excellent Bruised Orange, which was produced by Goodman, with classics like “That’s the Way That the World Goes Round” (later covered by Miranda Lambert) and the heartbreaking “Sabu Visits the Twin Cities Alone,” a meditation on loneliness from the point of view of 1930s film star Sabu Dastagir. “When I wrote that one and ‘Jesus the Missing Years,’ ” Prine recently told Rolling Stone, “I was afraid to sing them for somebody else. I thought they were going to look at me and say, ‘You’ve done it. You’ve crossed the line. You need the straitjacket.’ But if I let it sit for a couple weeks and it still affects me, it’s something I would like to hear somebody say, then I figure, my instinct is as good as a normal person. I would like to hear that somebody do that, so I just go ahead and jump into it.”

Prine’s offbeat odyssey continued with Pink Cadillac, a rockabilly album he made with Sam Phillips and Phillips’ sons Jerry and Knox. By 1982, Prine decided to follow the path of his friend Goodman and start his own label, Oh Boy Records, with Bunetta. Following a Christmas single, “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus”/”Silver Bells,” Prine’s first LP release was 1984’s Aimless Love. The business model, with fans sending in checks by mail, was a success, and early proof that singer-songwriters could survive without the support of a major label. “He created the job I have,” said songwriter Todd Snider, who released his early albums on Oh Boy. “Especially when he went to his own label, and started doing it with his own family and team. Before him, there was nothing for someone like Jason Isbell to aspire to, besides maybe Springsteen.”

In 1989, Sony offered to buy Oh Boy, an offer Prine turned down. Two years later, he scored one of the biggest successes of his career with 1991’s The Missing Years. Produced by Howie Epstein of Tom Petty’s Heartbreakers, it featured guest appearances by Petty, Springsteen, and Raitt. The title track, “Jesus the Missing Years” is one of Prine’s most ambitious songs, attempting to fill in the 18-year gap (from age 12 to 29) in Jesus Christ’s life unaccounted for in the Bible. It won a Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Album.

In 1988, Prine was in Ireland when he met Fiona Whelan, a Dublin recording-studio business manager. She soon moved to Nashville and they married in April 1996. By then, she had given birth to their two sons, Jack and Tommy. “It brought me right down to earth,” Prine said. “I was a dreamer. I learned real fast I don’t know anything except songwriting.” Prine also adopted Jody Whelan, Fiona’s son from a previous relationship. Jody and Fiona would eventually become Prine’s co-managers, overseeing the most commercially successful moment in his career.

This idyllic chapter of Prine’s life was complicated in 1997 when, during the sessions for In Spite of Ourselves — a successful duets album with women, including Iris DeMent, Emmylou Harris, Lucinda Williams, Patty Loveless — Prine discovered a cancerous growth on his neck. It was stage 4 cancer. “I felt fine,” Prine said later. “It doesn’t hit you until you pull up to the hospital and you see ‘cancer’ in big letters, and you’re the patient. Then it all kind of comes home.”

In January 1998, doctors removed a small tumor, taking a portion of the singer’s neck with it, altering his physical appearance. Prine thought he might never sing again. However, after a year and a half, he returned to performing, with a small show in Bristol, Tennessee. “The crowd was with me. Boy, were they with me,” he said. “And I think I shook everybody’s hand afterward. I knew right then and there that I could do it.”

The next decade brought Prine another Grammy for 2005’s Fair & Square. That year, Prine joined Ted Kooser, 13th Poet Laureate of the United States, becoming the first artist to read and play at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Prine saw his already formidable influence reach another generation of artists, including Jason Isbell, Sturgill Simpson, Margo Price, and Kacey Musgraves.

In 2013, Prine was again sidelined briefly, diagnosed with a spot on his left lung. Six months after the cancer was removed, he was back on the road. Following Buntta’s 2015 death, Prine became sole owner and president of Oh Boy Records, which has also been home to recordings by Snider, Dan Reeder, R.B. Morris, and Heather Eatman, among others.

His last studio album, The Tree of Forgiveness, was released in April 2018, just six months after he was named the Americana Music Association’s Artist of the Year. Rolling Stone said the album had “all the qualities that have defined him as one of America’s greatest songwriters.”