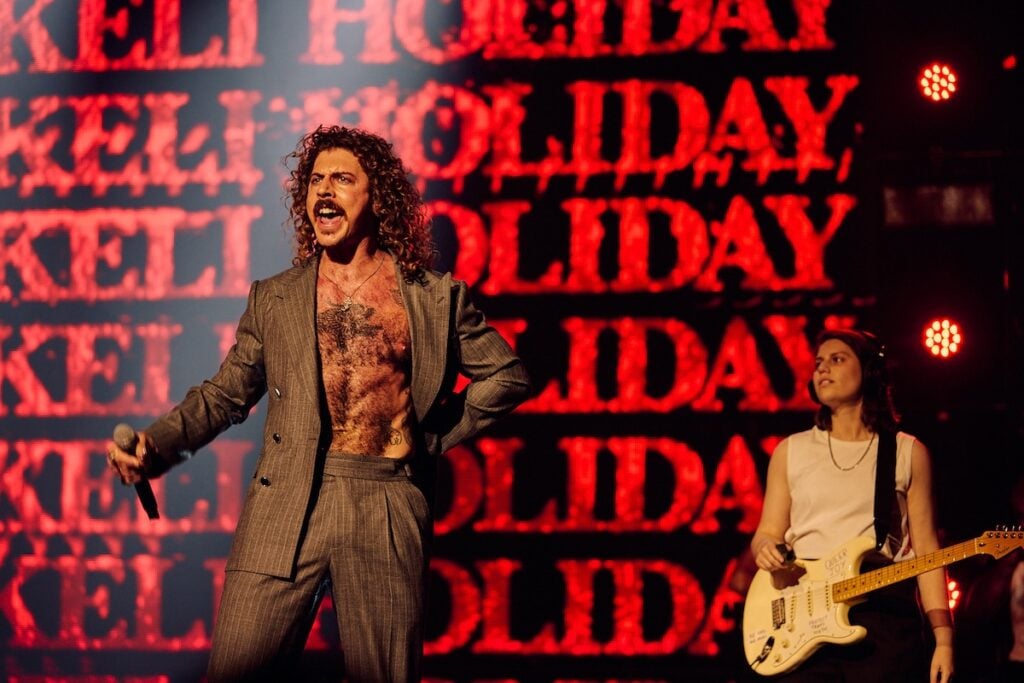

Inside the neon-lit, sweat-slicked world of Adam Hyde there exists a second skin: Keli Holiday.

For most people, Hyde is still best known as one-half of the electronic powerhouse Peking Duk. But for those who’ve followed the Holiday project since its inception in 2021, it began as a character defined by a specific kind of tragic bravado. In those early days, Hyde often described the persona as a “very confused, heartbroken man who still thinks he’s the shit.”

Now, with the impending release of his new album, Capital Fiction, the man in the mirror has changed — even if the DNA remains.

The evolution of Keli Holiday is not just a musical shift from high-gloss EDM to gritty, analogue-leaning rock; it’s an emotional sobering. While his debut was born from a depressive fog of late nights, introspection, and Joy Division records, Capital Fiction is a record of “radical optimism”. It’s a celebration of joy found amidst tragedy, a project that has moved past “whinging about a toxic relationship” to find something lighter, more hopeful. “I think there’s joy in nosediving,” Hyde says. “I think there’s joy in falling on your face and the hurt of it all.”

That optimism didn’t stay confined to the studio, either. Hyde’s single “Dancing 2” — a four-and-a-half-minute track with no definitive chorus and a sprawling sax solo — defied all conventional pop logic to claim the No. 2 spot on triple j’s Hottest 100, making it the top song by an Australian artist. It was a moment that validated Hyde’s decision to step away from the EDM machine and its rigid checklists of what a “hit” song should be.

Hyde is the first to admit that his early forays into the Keli Holiday world were more accidental than intentional. He views the project’s first songs as something he simply “slapped together” with no intention of creating a cohesive collection. “I don’t even call that really an album,” he says, reflecting on the haphazard nature of the project’s beginnings.

Capital Fiction, however, was approached with more precision. Hyde entered the studio with deliberate parameters — “a target on the wall,” as he puts it — shaping the first Keli Holiday record he feels truly proud to stand behind. “I went up to Queensland with a mission and had a target on the wall with certain parameters surrounding it, both sonically and ideologically, that I stuck to,” he explains. “So in that sense, I see this as the first Keli Holiday record that I’m happy to stand 10 toes behind and represent until the day I’m off this earth.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Despite the growth, he describes his current state with a characteristic touch of wit, noting that while Keli Holiday the artist has matured, his “scumbag” core remains. “I think I’m still the same old scumbag, just got some new shoes,” he laughs. This shift toward joy wasn’t about ignoring pain, but rather learning how to hold it up to the light — and sometimes laugh at it. Hyde views the “flamboyant and braggadocious” nature of the persona as a coping mechanism that he wears “like a shiny little badge.”d

The writing process for this album became more primal, governed by a simple rule of intuition. Hyde describes this gut-led approach in blunt terms. “Oh, does that feel good? Fucking run it. Does that feel bad? Throw it in the bin,” he says. “It was very primal in that sense. What doesn’t serve shall be chopped and what does serve shall be celebrated. And that was a fun way to do it.”

It’s a philosophy he took seriously, even when it meant leaving the room entirely. “If the answer’s no, get the fuck out of the room and go for a walk,” he says. “If the answer’s yes, stay in that room and fucking keep digging, boy.”

The Keli Holiday project has always been, at its core, a satire of toxic masculinity — a flamboyant subversion of the “tough guy” trope. Hyde finds a particular irony in the way men struggle to admit they aren’t okay, choosing instead to hide behind a mask of bravado. “I think it’s the never-ending game, especially for a lot of men is to say it’s all okay when they’re not and to not wear [their] heart on the sleeve even though it’s right there,” he says. “And I think there’s a lot of comedy in that. I don’t think it is this dire depressing thing. I think to look at it through a comedic lens is quite funny.”

The irony, of course, is that the project attracts hate from strangers, and trolls who epitomise the very traits Hyde is lampooning. Hyde’s response to the noise of the internet is one of amused and quiet defiance. “I think there should be controversy here and there in the game of any kind of entertainment,” he notes. “Otherwise, it’s fucking boring. Keep it spicy.”

Whether it’s the “Peking Cuck” remarks, the plagiarism claims, or the Wiggles controversy sparked by his “Ecstasy” video, Hyde remains largely unfazed, viewing the conflict as proof he’s at least making people feel something. “That ‘Dancing 2’ plagiarism claim is utter bullshit,” he says, dismissing the noise with the same shrugging self-assurance he brings to most things.

For Hyde, internet trolls are background static compared to the far more brutal internal voice that plagues most artists. When I remind him of a previous conversation about the inescapable voice in one’s head being the one that truly matters, he doesn’t hesitate. “I think that’s omnipresent with everyone,” he says. “It’s imposter syndrome [that] should just be called human syndrome. But through that, moments of joy is where it all matters.”

At the end of the day, he doesn’t believe anyone is exempt from that internal war. “We’re all on this freight train to hell or heaven. And if you’re on the train and there’s no music or there’s no books… you’re going to do something.”

Hyde views the facade he once hid behind as a personal choice he has finally outgrown. “The shield that I may have had prior was a shield that I built and a shield that I hid behind, and it was all my choice,” he admits. “It wasn’t forced upon me. Nobody had a gun to my head. So I was kind of a prisoner in my own little cage. And I think I enjoyed that in a weird way, but now I’m like, life’s short. We’re all going to die. Let’s fucking enjoy it.”

This sense of liberation is also reflected in his detachment from his past work. He views his songs as “offspring” that he must eventually let go of to avoid setting himself up for torment. “I’m grateful in the sense that I’m blessed with this sense of amnesia about these little babies that I’ve made,” he says. “But I’ll always love parts of each creation, the severity of which will vary. But I think if I’m not excited about what’s upon the other side of the mountain, then I shouldn’t be doing it.”

The DNA of Capital Fiction is deeply rooted in Hyde’s upbringing in Canberra: growing up in a town associated with order, politics, and restraint fuelled a powerful urge to escape into chaos. “Growing up in Canberra… you’re literally in a basin. It’s a crater. So I was born in the bottom of a basin,” he says. “And I think to look yonder and dream is an essential part of the human experience.” Hyde finds humour in the “dark shit happening underneath the surface” of such a well-ordered town, viewing Keli Holiday as the “curly-headed, broken-hearted vagabond” that emerges from the dark.

To find the authentic sound of this record, Hyde had to unlearn years of “polished high-gloss electronic music.” Working with producer Konstantin Kersting was pivotal in this journey. Kersting encouraged Hyde to lean into the “grit” and what Hyde self-deprecatingly calls his “shit singing.” He had to fight the habitual instinct to perfect every EQ and hit every note perfectly.

“I like if it sounds shitty and I like if I’m not hitting the right note in that vocal. It does something to me and I think it’s kind of weird,” he admits. “And with Kon, he was like, ‘Yeah, you’re a fucking weirdo, so be a weirdo, be where you are.’ And I think that’s the best anyone can bring out of anyone in any partnership.”

Hyde’s songwriting influences have shifted toward storytellers who prioritise delivery over technical perfection, citing Lou Reed and Shane MacGowan as inspirations. He finds romance in the “punk” simplicity of their work, recalling a story of Nick Cave finding “pure gold” lyrics in Shane McGowan’s rubbish bin. As Hyde explains his own vocal philosophy: “All my favourite singers can’t sing for shit. Lou Reed, he doesn’t sing. He just talks with style. And I think that’s my lane.”

This analogue world has allowed Hyde to connect with people on a deeply human level that feels distinct from the EDM circuit. While Peking Duk is “the best party gig in town,” Keli Holiday offers more nuance. The result is a diverse audience that ranges from 18-year-olds to fans in their 70s. “I think sweat-covered smiles is like that’s what you want to see at the end of a show,” he says. “And some tears is pretty crazy, too.”

Operating as an independent artist has provided Hyde with the freedom to be “messy” and impulsive. To him, independence means everything from putting music videos on PornHub to executing a social media strategy without being swayed by charts or trends. It also means chasing the uncomfortable rooms, not just the easy ones. Hyde finds something perversely motivating about the idea of a hostile crowd. “Playing pubs in rural Australia to 10 people that hate me? I love that,” he says. “Playing to thousands of people that adore you, that shit’s easy. Playing to thousands of people that hate you, that’s where the fucking real work comes in.”

“To do it all independent too is fucking awesome. I mean, I’m here for the new style. It’s a lot more work, but it’s hungry work and I’m a hungry man, so I’m game for it,” he adds. “I used to be so focused on producing beats and things like that, whereas now I do love making a beat and I love shaping beats, but what really turns me on is trying to get to a place of writing something that really feeds me, feeds me, feeds my heart. That’s the best I could do with my time on this earth… so I’m going to keep doing it.”

Ultimately, Hyde’s goal for Keli Holiday is simple: connection and honesty. “I just want everyone to lean into what they feel. I think trust your instincts, listen to your emotions, love loudly, be yourself for yourself and show up. Just keep showing up. We’re all in it together, and love shall prevail,” he says.

When asked what legacy statement he would give Capital Fiction years from now, he doesn’t reach for anything grandiose. “Turn it up,” he says. “Yeah. I mean, that’s all I can think of. I’m just thinking about all the synths and shit. Just turn it up.”

Keli Holiday’s Capital Fiction is out now. Check out his upcoming tour dates here.