Supplied

Travis Were the Biggest Band in Britain. Why Does It Still Feel Like They’re Underrated?

They toured with Oasis three times and influenced Chris Martin and Coldplay. But Travis have always just been "almost fashionable."

“I loved Glasgow but that love has always been matched with an urge to leave, to see over the horizon, and that pull has made me a proud citizen of the world. Yet there’s always been a string in my heart that I’m glad pulls me back to where I’m from. To all the things that made me good and bad: Scotland.”

— Billy Connolly

December 20th, 2024. It’s a bitterly cold night in Glasgow, and karaoke is in full swing inside the much-loved Horseshoe Bar. “Why Does It Always Rain on Me?” by Travis is the next song — a likely thing to happen at a Scottish pub. What’s less expected is who steps up to sing: rocking spiky, shock-red hair which wouldn’t look out of place atop Oor Wullie’s head, Fran Healy appears on the well-worn wee stage, whereupon he eagerly belts out his own song, joined in (drunkenly out-of-step) unison by pub revellers.

When Travis first became Travis as we know them now — Fran Healy at the front, Andy Dunlop on guitar, Dougie Payne on bass, Neil Primrose on drums — they would practice above the Horseshoe Bar in Glasgow. It helped that Primrose pulled pints there, and the rest drank cheap Tennent’s between recording sessions.

But that was around 1994, and Travis’ members have spent most of their time outside of their hometown since then, jetting around the world as part of Scotland’s most consistently successful rock band.

Why, then, has it taken Travis so long to tour Australia? When they finally return in January for shows in Fremantle, Melbourne, Adelaide, Sydney, and Brisbane, it will be almost a quarter of a century since their last visit. What gives?

“It’s down to the [top] brass, management, agents, all the people who run the business,” Healy says ruefully, calling in from his Los Angeles home. “It’s generally decided, all your touring, all your logistics… all that stuff’s decided by other people.” His demeanour brightens. “But we recently got our baw back.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

This “baw,” I presume, is a reference to Travis bravely parting ways with their management company of 25 years, Wildlife Entertainment, in 2021. “It’s a new year and a new creative chapter for Travis. Off we go,” the band shared in a statement at the time; “[i]t was one of the most empowering moments we’ve had recently,” Healy would tell the BBC a few years later.

With the power back within the band, they decided to tour Australia as well as America for the first time in a long time. “There’s loads of places that we’ve yet to go or we haven’t been for a while. So we’re hitting these places now,” Healy says.

Their last Australian tour was so long ago, that his memories of the trip are murky. “I remember getting there and it being cold and rainy and going, ‘What? Really?’ I came over, I think it was maybe July or something. Yeah, it was around July time. It was the middle of winter. I was like, ‘What?!’”

If there’s one thing Glaswegians like Healy understand better than almost anyone else, it’s the rain. The incessant, fuck-your-summer-plans rain.

“They say, ‘Oh, I went up to Scotland once and it was raining.’ Of course it was fucking raining! Where do you think Scotland is – the fucking Pyrenees? Take a raincoat, you stupid fucker!” Billy Connolly, Glasgow’s greatest storyteller, once said, barely concealing his contempt for naive visitors. So it’s no wonder that if you get two Glaswegians together in a room — or on a Zoom call – the topic of the weather won’t be far away.

“I remember when I got to Melbourne and I got my first day of rain, I was like, “What’s the point? What am I doing here?’” I tell Healy. He’s clocked my accent.

“Where are you from?”

“Moodiesburn,” I reply.

“Moodiesburn! Everybody knows [there] because the name’s memorable.” It’s almost certainly the only time an Ivor Novello winner will recognise the name “Moodiesburn,” and it’s surely the first and only time a mining village on the outskirts of Glasgow will be mentioned in the pages of Rolling Stone.

“It’s right on that main road, the one that goes between Edinburgh and Glasgow, so you have to pass it… It wasn’t a nice place once you got inside it, but aye, nice name.”

Born in England but raised in the heart of Glasgow, Healy has spent the most successful years of Travis living in music hubs around the world, from London to Berlin. He’s called LA home for almost a decade, working out of his studio on Skid Row.

Despite not having lived in his hometown since his early 20s, his accent is still unmistakably local, just a little softer on the ears. I tell him that I need to get home to “sharpen the accent” — it’s been eight years since I was last in Scotland, and my Glaswegian “aye” has more and more morphed into a sloping, Kiwi “yeah” recently.

“No, no, your accent is good,” he assures me. “I don’t listen to shows because they’re kind of fleeting. But someone was going to put it out somewhere and I had to listen to it… and I was fucking singing in a kind of American accent. As you know, being Scottish, [you] don’t ever lose your accent because it’s your identity, and maybe even more than that. Maybe if we had longer we could talk about it… but on that one song I was like, ‘Oh no, I’m sounding like a fanny!’”

As if to atone for this self-perceived mistake, Healy sounds more Scottish on record than ever on “The River”, a standout track from Travis’ most recent album, L.A. Times (2024).

“It [the accent] comes out. So you must be proud of that one,” I say.

“Yeah, absolutely… Again, it’s weird. I don’t identify as Scottish first, I identify as Glaswegian first.”

“Me too. I’m glad you said that.”

“Because our blend — Glasgow is a blend of Irish and Scottish. [You] get the pure Scottish, which is kind of coming in from Sweden and the Scandi[navian] sort of place[s]. They’re, you know, hairy guys, and we’re all diminutive, urchin-like people… We wouldn’t look out of place in a Lord of the Rings movie!”

Travis are a very Glaswegian band. They are, in local parlance, ‘mixed’: Healy is the only Celtic fan, outnumbered by his three Rangers-supporting bandmates. “It’s a strange balance,” he laughs. Aside from Dunlop, they all attended the cherished Glasgow School of Art, working odd jobs around the city at the same time as pursuing studies and music.

Their chances of success, however, lay far away from the Horseshoe Bar and their home city.

“[T]hey weren’t really getting any better, just treading water,” recalled Charlie Pinder, then-Managing Director of Sony Music Publishing UK, in a 2001 interview.

“Then they split with the manager they had at the time, recorded a demo with about five songs and decided to move to New York as they felt the US might be more suited to their style of music. They had been repeatedly knocked back by the British record industry and couldn’t afford to hang around for another five to six years… We moved them to London, we got them a rehearsal room, we got them a house, we recorded more songs and that took about nine months/a year. Then they were ready, the lineup was complete and they had about twenty fantastic songs.”

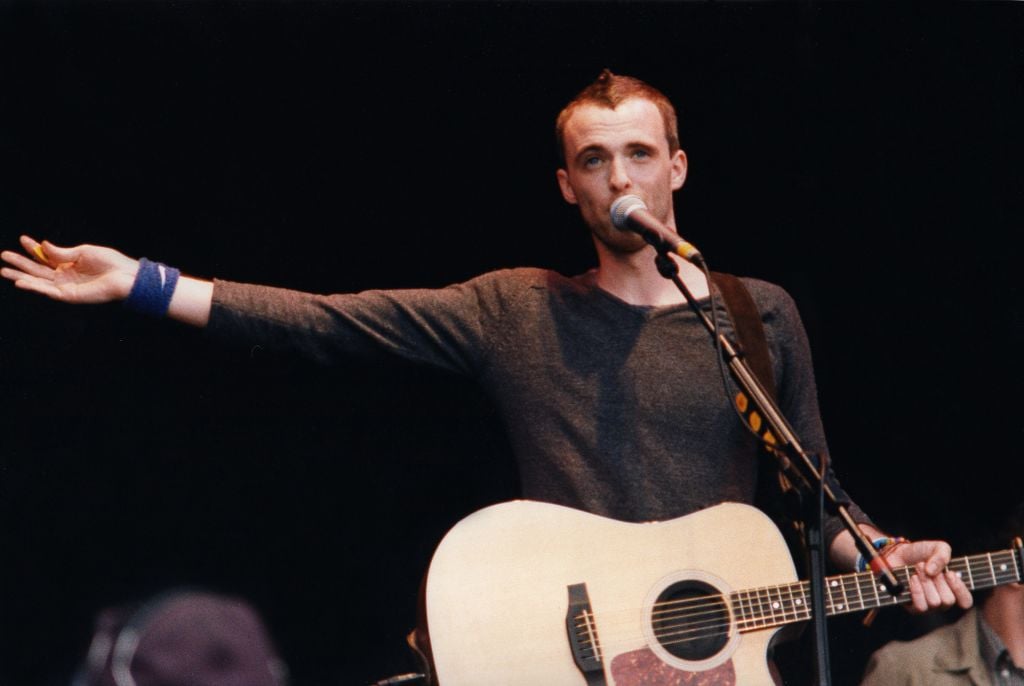

June 26th, 1999. Travis are a few songs into their set on Glastonbury’s Other Stage, when Fran Healy notices some ominous clouds gathering over the festival — call it Glaswegian intuition. After being sunny for much of the day, a deluge of rain suddenly falls from the sky, just as they play their new single “Why Does It Always Rain on Me?”. It’s a moment a screenwriter would discard for being too saccharine, but it proves to be the highlight of Glastonbury, leading to BBC presenters Jo Whiley and John Peel calling them “the band of the weekend.” Travis’ career will never be the same again.

Travis’ initial rise is inextricable from its historical context.

Their first album, Good Feeling (1997), was a solid if unspectacular debut which did little to separate Travis in the minds of critics from the multitude of Britpop bands storming the mainstream. Good Feeling initially sold a respectable 40,000 copies, peaking at No. 9 on the UK Albums Chart, but, if someone listened close enough, there were plenty of signs that Travis were no middling Britpop outfit.

“We’re tired of the ‘90s / We’re tired of the ‘90s / But we’re tied to the ‘90s / Tied to the ‘90s,” Healy sang in the lightly satirical “Tied to the ‘90s”, sagely pre-empting the fate that befell so many of their contemporaries (and could have befallen Travis too); “U16 Girls” offered a tongue-in-cheek warning about the perils of getting into a relationship with a girl whose mature looks bely her age.

In the year Travis’ debut dropped, Britpop was coming to a shattering end. It’s still uncertain as to the exact moment “Cool Britannia” ceased to be cool. Maybe it was when it was politicised by New Labour, Tony Blair calculatedly aligning himself with figures like Noel Gallagher; maybe it was the mixed reaction Be Here Now, Oasis’ highly anticipated third album, received; or maybe it was tied to when Princess Diana died, or, the year prior, England went out of Euro 1996 on (what else?) penalties.

The end of Britpop also seemed to be tied to something more deep-rooted than those surface events, a sort of spiritual malaise setting in after years of hubris and braggadocio and — gulp — lad culture. As a new millennium approached, accompanied by the anxiety attached to a dawning of that magnitude, British people, it seemed, wished to slow down and get reflective.

“We were a bit dejected… nothing seemed to stick,” Healy said of the band’s initial post-Good Feeling era in a 2019 Clash interview.

They first decamped to France to record with Mike Hedges (The Cure, Manic Street Preachers), but their second album really began to take shape when they returned to London to work with the imposing Nigel Godrich, who had just produced Radiohead’s seminal third album OK Computer, a major record in the transition away from the Britpop era.

“Nigel kind of turns [sic] up and we went in the studio with him and that’s when it was like, ‘My God, this sounds great,’” Healy reflects. “[I]t sort of pulled us left of centre. [H]e was kind of at the absolute top of his game and it was luck [sic] to get him.

Healy has high praise for his friend and former collaborator. “[T]o this day, there’s not been anyone I’ve been in the studio with who you sit in front of the speakers and you’re like, ‘Wow, he’s kind of a magic engineer.’ [I] don’t know how he does it, but he’s got a much different approach than anyone else I’ve ever worked with.”

The album which Godrich helped birth, The Man Who (1999), started out with a trick.

“Writing to Reach You”, the opening track, was pure Britpop, Healy lifting the chords directly from Oasis’ incredible or interminable, depending on whom you ask, “Wonderwall”. In being so trenchantly in conversation with one of its defining anthems, Travis’ second album seemed to announce from the outset that Britpop’s overwhelming presence was near-impossible to escape.

And then came the rest of The Man Who.

The proceeding nine tracks were mostly mellow and always contemplative, the chill come-down to Britpop’s come-up anthems. The album was filled with gentle acoustics and mid-tempo cuts. Godrich’s production skills brought out spacious, graceful textures, and there was even a touch of his Radiohead collaborator Thom Yorke in Healy’s oft-wailing vocals.

Travis’ album was by no means groundbreaking, but it was tender and understated, primed for “Sunday sessions.” The post-Britpop era had its first defining record.

Over 25 years later, the astronomical success of The Man Who is still scarcely believable: over 3.5 million copies sold worldwide; three Brit Award nominations in 2000, with two wins (British Group and British Album of the Year; an Ivor Novello for Best Contemporary Song (“Why Does It Always Rain on Me?”).

“It’s a mystery to me,” Healy told Clash, reflecting on that special time. “It definitely connected and maybe it connected because of the Britpop thing, that candle was just flickering and we had just lit ours.” When Travis returned to Glastonbury the following year, it was for a triumphant Pyramid Stage slot.

May 11th, 2002. A young Scottish boy knows what he’s getting for his seventh birthday. Amazed at discovering his father’s CD rack, featuring foreign names like the Beatles, Madonna, Simon and Garfunkel, and David Gray, he asked if he could get some of these CDs for himself, thanks. On this birthday morning, three CDs, tightly gift-wrapped, are waiting on the living room table. They turn out to be: The Man Who by Travis, something by Westlife, and Sing When You’re Winning by Robbie Williams. He’s only excited about the Robbie Williams one, to tell you the truth.

It was uncool to like Travis when I was a child. Like, really fucking uncool. The British music press at the time certainly thought so, almost unanimously ganging up on The Man Who. They really didn’t like the swerve into melancholic territory, away from the rockier Good Feeling. They deigned that their second album was soporific nonsense, just a bunch of nice guys from north of the border making bland music. Nice but dim, seemed to be the accusation. Nice but boring. Harmful because of their harmlessness. Travis became a byword for everything mainstream and dull, and it definitely didn’t help that they were inescapable for a long time. Is that them on the radio? You bet. Over the supermarket tannoy? Aye, probably. In a CD in your dad’s car? More than likely.

“[W]e brought out The Man Who and they [critics] were like, ‘Kill them!’ Weirdly, all the reviews were terrible,” Healy recalls in bemusement. “Luckily, it just goes to show you don’t really know how things turn out. You can’t predict it.”

“I think that’s why lots of critical reviews are better 10 or 15 years after,” I say. “They can take the time and actually appraise the record.”

“Do you do critic[s] stuff?”

“I do.”

“Well, talking over the years to everyone, you realise that, when you get a bunch of records to review, you don’t get any time to live with them. And why a lot of journalists and critics stuck their noses up at us was because certain ones, almost like the sixth-year prefects, you know, they were like, ‘Nah, fuck them, they’re shite.’ And everyone’s like, ‘Yeah, they’re shite.’”

“Like a herd mentality.”

As if to encapsulate this point, US reviewers, far away from an island whose journalists were still desperately clinging to the last vestiges of Britpop, were much fairer to The Man Who, writing in good faith, unburdened by egos, or spite, or a desire to fit in.

“Travis fulfills the musical equivalent of this basic human need for the occasionally mundane. While by no means groundbreaking, The Man Who massages with sincerity and crisp precision,” Pitchfork wrote in a positive 7.8 review, calling the “raw humility” of the band “refreshing.”

Even as recently as 2016, the British press were showing open hostility towards Travis. Writing in bad faith on their eighth album, Everything at Once, The Guardian’s Tim Jonze said: “In many ways, this Travis record is no better or worse than previous Travis records. You still get your plangent guitars, your harmless jangle and Fran Healy’s way with an inoffensive semi-melody… Have they always done that sort of thing? Maybe. Let’s be honest, I’ve not exactly been keeping track. The question here is: should we be showering praise on Travis simply because they’re performing at optimum Travis levels? Doesn’t that amount to moving the goalposts a little? We don’t say the brutal crushing of the miners was just Thatcher doing what Thatcher does best and award it four stars, do we? And neither shall we with this.”

“I don’t know why,” Healy reflects on the British press’s hostility. “I think maybe because where we’re from — we’re nice. Nice is misunderstood as weak. As you know, coming from Glasgow — or Moodiesburn, but it’s Glasgow — you’ll know that people are nice, but we’re not weak. We’re the opposite, actually.”

“We’re gentle, we’re gentler. Travis are much more gentle [than other rock bands], but we’ve got a sort of gnarly edge to us as well.” (Comedian Kevin Bridges has a great bit. It goes something like this: “The city of Glasgow was recently announced as Europe’s murder capital, but also voted the UK’s friendliest city in the same week. We got our act together pronto. You might get the shite kicked out of you but you’ll get directions to the hospital.”)

If a hostile British press didn’t get to you as a young Glaswegian band, your own city just might. Riddy Culture — a particularly pervasive and caustic cousin to the Antipodean Tall Poppy Syndrome — is rampant in Glasgow, or certainly was during the ‘90s and early ‘00s. This is the essence of Riddy Culture: in a city which prides itself on being authentic and humble and unpretentious, a person should never get ideas above their station; you can be a success, aye, but don’t ever forget where you came from.

In the immediate post-Britpop years, the British press seemed eager to make Travis vs. Coldplay the new Oasis vs. Blur — Coldplay frontman Chris Martin even publicly acknowledged that Travis were “the band that invented my band and lots of others” — but Travis’ humility never let it become a thing.

Because there was a crucial difference between Travis and Coldplay: one wanted to be famous, the other did not. In an Independent interview celebrating The Man Who turning 20, Payne summed up the distinction between the bands nicely: “They [Coldplay] were a bit more strategic. And a bit cleverer! Put it this way: they’re university, we’re art school. That’s the fundamental difference. We’re a bit more chaotic and, as they say round here, haun’ [hand] knitted. But you can’t begrudge them anything because they just worked their balls off, and are completely driven and single-minded. We’re a bit more vague.”

Noel Gallagher was another early admirer of the band, despite Healy so blatantly ripping off “Wonderwall” on “Writing to Reach You”.

“[…] I thought I could put something in there in case he ever in a million years gets to hear this… We played it on stage for the first time when we were supporting them. Noel was watching it and I was like, ‘No, I didn’t expect this to happen,'” Healy remembers.

“Did he like it?”

“As I was walking past, as we walked off stage, he sort of leaned in nonchalantly and said, ‘Nice fucking chords.’”

Travis ended up supporting Oasis on tour three times, and Healy remains close friends with the band. Oasis begin their own Australian tour, part of their worldwide reunion run, this week, and he couldn’t be happier for them.

“I met Noel in New York and I met the rest of them in New York as well. I didn’t see Bonehead until they played in LA a few days later,” he says, adding that they feel “no pressure.”

“Like, of course not. I mean, there is no better position to be in than a band who has, like, 18 massive songs or 20 massive songs. And they could literally do it with their hands tied behind their back… It’s like being on the best holiday ever. And they’ve got their families on the road, and they’re just having a ball.

“Liam’s singing better than he has ever sung. I think that’s the big difference… Liam’s almost like being an athlete about it. He’s not smoking, he’s not drinking. He comes in just before the show and leaves right after it. And doesn’t get hammered or whatever. Noel’s having a blast. They’re playing great.”

Healy and his bandmates never wanted fame — but The Man Who forced it upon them. Little wonder its follow-up, 2001’s The Invisible Band, came with such a pointed title. “We weren’t celebrity or tabloid types,” Payne said in that same Independent interview. “We weren’t good at being celebrities.”

The Invisible Band unsurprisingly topped the UK Albums Chart, staying at the summit for four weeks, outselling its predecessor in that time. Behind the scenes, Healy and his bandmates were, to use a Scottish word, scunnered, struggling after recording battles with the returning Godrich, who was just as tired as them following his own production troubles on Radiohead’s Kid A, and years of touring in the UK and beyond. When Primrose broke his neck in a swimming pool accident in France the following year, it was another crystallising moment for the band, and a serious wake-up call.

September 2023 (Date Unremembered). It’s closing time at an Irish bar in Auckland CBD, one that’s seen better days. A 28-year old alcoholic (semi-alcoholic, he keeps telling his friends and partner) is swinging a half-full glass of whiskey — his sixth of the night — precariously in his right hand. Here’s how alcohol affects the 28-year-old semi-to-full-alcoholic man: others get sick, he gets homesick. Very homesick. The tired bartender says it’s last call, but a familiar song plays out over the speakers. The half-full glass of whiskey is slammed down on the table, and the man turns to face his captivated (captive?) audience. “Here, by the way, this song is fuckin’ class. Fuckin’ turn it up. I loved this band when a wis’ young. Here we go.” He begins to sing wildly out of tune: ‘I can’t sleep tonight / Everybody’s saying everything is alright…’”

In 2018, Travis decided to turn the other cheek as only they could.

They invited the English rock journalist Wyndham Wallace, one of those critics who loathed, or, at least, strongly disliked the band, to accompany them on their global tour.

The experience turned into Almost Fashionable: A Film About Travis, which debuted at Cannes in 2018, later receiving its British premiere at the Edinburgh International Film Festival.

“I thought it would be interesting to bring a journalist who didn’t like us on the road with us,” Healy says. “Not challenge them but just have them around us because everybody that meets us is suddenly like, ‘I thought you were like that, but you’re like this.’ So anyway, it’s a good documentary,” he adds.

A positive aspect of Riddy Culture, if there is one? Learning to resist the world of glamour and celebrity. A Glasgow boy can enter this world, even occupy it, but he won’t get carried away with himself.

“We didn’t wear the clothes and we didn’t play the type of music that was in fashion. We’ve always been on the outside of it,” as Healy told Clash.

He has a story to illuminate this point.

“My claim to fame is that I was at some party here [LA], maybe a couple of years ago, I was invited by the woman in the Bangles, Susanna Hoffs [she provided vocals on Travis’ 10 Songs album]… She’s like, ‘I’m having a party, come on over,’ and I’m like, ‘Okay.’

“And I don’t really do those types of things, but she’s kind of low-key anyway, I thought, but [there] was like a lot of quite famous people at it, and Neil [Finn] from Crowded House was there, he got us up to sing backing vocals to [Crowded House song] ‘Weather with You’. And it was mad, it’s one of those moments that I was sitting beside him going, ‘I can’t believe this is happening, this is fucking cool.’”

“That feels like a very LA thing,” I crack.

“Yeah, and he was lovely and his songwriting is tremendous. I thought, ‘God, I don’t know that song.’ As soon as he started singing it, I knew all the BVs [backing vocals] and everything. And it was great.”

And Healy likes to name-drop. A lot. “That album’s got Paul McCartney playing bass on one of [the] songs,’ he says casually about his 2010 solo record, Wreckorder.

Two very famous names, Chris Martin, and The Killers’ Brandon Flowers, provided vocals to “Raze the Bar”, a track about a famed New York City bar frequented by Healy which featured on L.A. Times.

“Chris is an old friend – we’d go round his and Gwyneth’s place when our kids were babies, and then we lost touch a bit when I moved to Berlin,” Healy told the BBC. “A while back I was dropping [Healy’s son] Clay off at a gig and I didn’t realise it was Chris’s son’s gig. I’m driving out the car park and I saw Chris walking across it with Dakota [Johnson]. So I wound the window down, put on the broadest Glasgow accent I could manage and went ‘hoi – you!’ He jumped a mile.”

Struggling to gain the necessary distance from Travis’ latest album, Healy took Martin for a drive up California’s Pacific Coast Highway to play him the new record in the car. Soon after, the pair were finishing off a new song around the piano back in Martin’s LA home.

“A few days later I asked him if he wanted to sing on the chorus and he was up for it right away,” Healy told The Herald. “He was talking about Donna Summer getting a bunch of uncredited mates in [sic] to sing on a song and said I should do the same. Brandon was really my only other big celebrity band mate. So I texted him and he was like: ‘Sure, man!’” (Flowers, too, is indebted to Healy’s band, having played Travis songs at open mic sessions before the Killers’ rise to fame.)

The level of fame Travis have reached, I suspect, is the maximum level of fame that can be tolerated by a normal person — a.k.a. me or you, or your neighbour or co-worker. Anything above this level of fame — oh boy. Healy and his bandmates don’t have every tabloid newspaper covering their tour, desperately looking for any sign that all is not well off-stage; they don’t have to work with superstar boybands, constantly under pressure to maintain relevance and release a megahit. They can craft one of their very best albums (L.A. Times) two decades into their career, try new techniques (Healy utilises an almost Sprechgesang style on album track “The River”), and not be disappointed that it just misses out on the top spot of the charts at No. 2. Those British journo posers of the late ‘90s would likely accuse this level as being safe and unadventurous — they’d be wrong.

But Healy has always been ambitious — even bullishly driven. It was Healy who expedited the removal of two founding members of Travis, brothers Chris and Geoff Martyn, replacing them with his friend and amateur bassist Payne.

“The band had been going for a few years. The four of us had been pals, but the band had been going as a five-piece called Glass Onion for a few years. Fran [Healy] was like, ‘Something needs to change,’ and then he was like, ‘I want you to join the band,’” Payne recalled to Far Out Magazine.

Yes, “Writing to Reach You” was played off as a joke, but it was also gallus (a Scottish word for cheeky) in its execution. That famous Glastonbury performance? Healy thought it was weak. Before that festival made “Why Does It Always Rain on Me?” a defining song of its time, Healy shrewdly thought of aligning it with Wimbledon. “It’s gonna be sunny and then it’s gonna rain like it does every year, and maybe the BBC will pick it up,” he told The Ringer. “It was sad and desperate.”

Just read a selection of lyrics from “Driftwood”, one of the key tracks on The Man Who: “Everything is open / Nothing is set in stone / Rivers turn to ocean / Oceans tide you home / Home is where your heart is / But your heart had to roam,” Healy sings at the start, before the song closes with “[b]ut you’ve been drifting for a long long time / You’ve been drifting for a long long time.” These are the existential words of a songwriter keenly aware of the life-changing opportunity he’s been presented with.

So here we are. Travis have shown remarkable consistency for a band who first rose to prominence in the mid-90s, and much more sustained success than most of the bands who came up with them at the same time.

“You’ve released an album every like three years roughly over your career,” I note. “There’s not many of your peers from the ‘90s that can say that…”

“We’ve never had a grand plan,” Healy says. “I think that’s a good thing… Our mantra is always, like, we want to be the best band, not necessarily the biggest band, because when you’re the biggest band, that comes with a whole load of things that are expected of you. To do a certain thing or to follow a certain thing. That’s why we’re ‘almost fashionable’. We’re just a little bit out to the side of it.”

Being raised in a proudly working-class city surely has something to do with this longevity, too. In a 2024 Guardian interview, Healy answered some quick-fire questions. One in particular stood out: “What did you want to be when you were growing up?” Healy’s response was short: “”Not poor.”

“I think that is a Glaswegian mindset,” I tell him now.

“Mm-hmm. Yeah. Like if you don’t know that feeling, it’s like a superpower. It never leaves you. I’m not tight or anything. I’ve got this mad — I worry that I would [sic] ever be poor again. ‘Cause it’s the most limiting thing anyone can do. And when you’re poor, nothing’s on the menu.

“I remember going to a nicer school when we moved across to the southside and you’d see people talking about going to uni and I’m like, ‘What’s that? What’s this thing called uni?’”

July 12th, 2024. A vintage double decker bus — a beautiful green and gold special, cruelly replaced in the new millennium by the staid all-white fleet — trundles through Glasgow. Travis are on board, busking throughout the city centre. Fran Healy hangs out the back, filling the conductor’s position, wearing a bright orange jumper that blends in with the bottom half of the bus. People passing by on the street seem confused, or elated, or both. Singing songs and trading jokes, Healy has never looked happier, an onlooker could surmise.

Healy is in the midst of a seismic period of change. His 19-year-old son, Clay, just left for college, to be replaced in their family home by Healy’s mother, whom he’s picking up in the UK the day after our call and bringing to LA for three weeks. Lounging on a brown leather couch, surrounded by pillows, he’s a man finally enjoying some space for himself, if only for a while.

“I mean, I was messy but I’ve gotten tidier as I got older, but he’s [Clay] at that stage where literally it’s, like, atomised,” he says. “He’s got so much shit. I thought, ‘This will take like half an hour…’ Fucking four hours later!”

Soon, he’ll be back to endless airport lounges and long-haul flights, first to Japan for two shows in early January before Travis land Down Under. Maybe a tour on the other side of the world is what he needs. Healy has passed through some turbulent years, during which his marriage ended and he lost one of his close friends to cancer (music video director Ringan Ledwidge, who passed away at the age of 50 in 2021). Add in the ousting of Travis’ long-term manager, as well as his son heading to art school in New York, and it’s a catalogue of events that would leave anyone feeling existential.

Not everyday you see @franhealy from @TravisBand hanging oot the back of a routemaster in Glasgow belting out tunes! Glorious marketing; still sounding ace! Streaming #Travis all day since, sooo many bangers👏🏾❤️ See you guys at the Hydro in, I’m locking that in!🫶🏾 #LATimesBus pic.twitter.com/OTaMuSPifx

— ⫩ Suz ⫩🎵 (@Scottish_Suzi) July 13, 2024

Returning to life on the road returns him to the one constant in his life since the mid-90s: Dunlop, Payne, and Primrose — Travis.

“You’re not quite friends, you’re more than that but you’re not quite brothers,” Healy told the BBC. “Instead you’re in-between that. When we come offstage we’re very close, like a football team that’s been together for 30 years. It’s very sweet and very rare. If you’re in a band it’s like you’re in formaldehyde because it keeps your spirits in the same place.”

Healy has one other memory from his last Australia trip: “I remember it feeling very familiar. I don’t know about you, but it feels kind of a bit homey to me. Maybe it’s the humour, maybe it’s the sort of not taking things too bloody seriously.”

You’ll find that in the crowds,” I say. “Scottish crowds are amazing, but the Aussie crowds go for it as well.”

That’s why it won’t be two decades until Travis are back in Australia, he insists. “It’s such a long time! This [upcoming tour] is the first of a new chapter.” New Zealand tour dates, too, could come sooner rather than later. “[W]e usually do [come to New Zealand], and I don’t know why that wasn’t connected [to Australian tour dates]… I have to have a word… We did talk to the agent about it, but again, I don’t know.”

As sure as the rain falls in summer in the city, our conversation swings back to Glasgow.

“[O]ur humour is something else,” Healy says. “Like we were doing last year, we went round Glasgow on an old corporation bus, just blaring the album [L.A. Times] out and sort of verbally assaulting passersby. And I had the mic and I was just being rude to people. And it was funny, but we stopped at the [Glasgow music venue] Barrowlands and did a little on-the-street performance.

“We were figuring out what song we were going to play and I was like, ‘Right, ready? Right, one, two, three, four.’ And then somebody went ‘five.’ To me, that’s our weird fucking humour, you know?”

Ticket information for Travis’ Australian tour is available here.