Rock ’n’ roll lovers born post-Noughties, especially those fond of wearing Nirvana T-shirts, may nostalgically look back at the Nineties and fetishise it as the era when grunge and guitar music dominated the cultural conversation. Sydney band Big Heavy Stuff were right there in the trenches to experience it all firsthand, touring relentlessly and releasing music at a time when the concept of “selling out” was less applauded attribute and more artistic suicide.

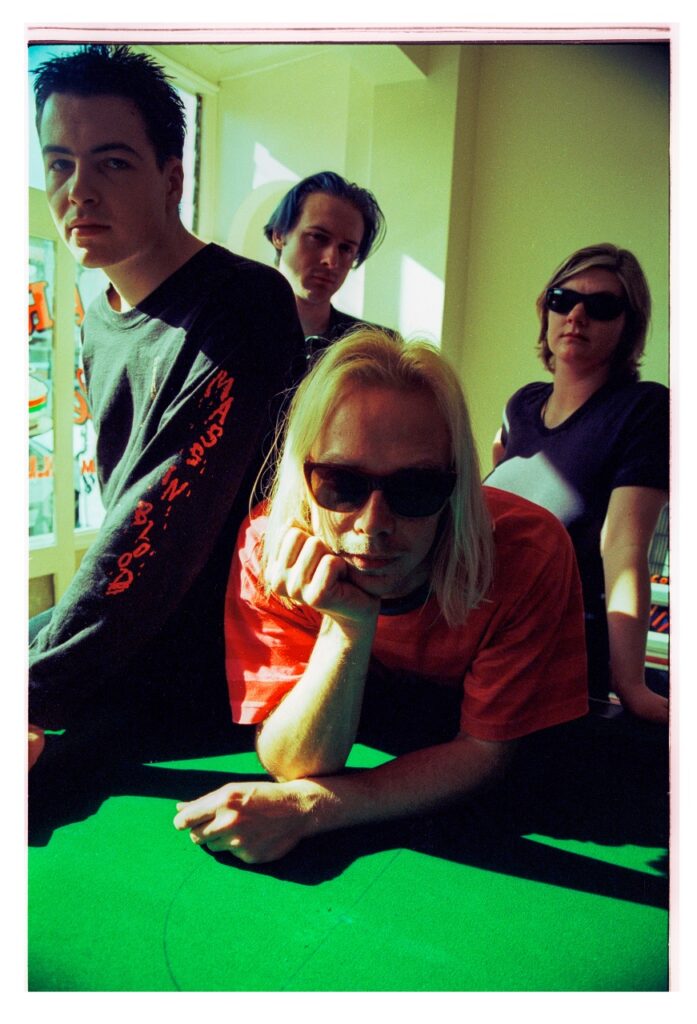

After a debut album (1993’s Truck) and a couple of EPs, a shifting lineup stabilised into the quartet of Greg Atkinson (lead vocals/rhythm guitars), Carolyn Polley (lead guitars/backing vocals), Eliot Fish (bass), and Nick Kennedy (drums) on 1995 EP Covered in Bruises. The foursome went on to tour with the likes of Radiohead and the Stones Roses, crack the triple j Hottest 100 in 2001 with “Hibernate”, and record three further LPs before dissolving in 2006.

Drummer Kennedy joins me in the artistic-leaning, inner-east suburb of Surry Hills, a short distance from the now defunct Hopetoun Hotel, a one-time mecca of live music and a regular Nineties haunt for not only Big Heavy Stuff, but pretty much every band in town.

“A bunch of us were the right age, and we were living in and around this area, and it was like [TV sitcom] Cheers – there’d always be someone there that you knew,” says Kennedy. “You were never at a social loose end, because you could always go to the Hopetoun.”

Although Kennedy is nostalgic for venues like “The Hoey” and the communal, live music-friendly atmosphere it fostered, he says he doesn’t want to suffer a similar fate to the beloved pub.

“It’s my worst nightmare to become the Nineties relic that [The Hopetoun] has become,” he says with a laugh. “That’s another reason for the [Big Heavy Stuff] reissues. The music deserves to stand alongside timeless music, and in my opinion it doesn’t have to be caught in that specific time. I think people from that specific time will enjoy it, but I’m hoping that people who weren’t there, who are just music lovers, can hear it and enjoy it too.”

The band’s unofficial archivist (“I’ve been the one that always made sure we had a copy of anything we did,” he says), Kennedy has been instrumental in getting the aforementioned vinyl, CD, and cassette reissues (2001’s Size of the Ocean, 2004’s Dear Friends and Enemies and Live at triple j 2004) released on boutique label Love As Fiction.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Next up is Bruises, a double LP that collects the band’s 1995 EP Covered in Bruises along with a dozen non-album gems, many unheard, capturing a band at its creative peak.

“When I started going back, I just couldn’t believe how much stuff there was,” says Kennedy. “We were always a pretty prolific band, and Greg always wrote stuff, always had stuff in his back pocket, but I’d forgotten how much of it we’d recorded. We must have rehearsed a couple of times, recorded [a song], and then didn’t think about it again for 30 years.”

Before the remixing and remastering process could begin, Kennedy says the original tapes needed to be “baked” to ensure they would be usable.

“These tapes sit in storage in various stages of dampness or whatever, and sometimes they’re not even in cases,” he explains. “Big Heavy Stuff never really considered our master tapes to be assets – nobody really did until recently. It was like, ‘Yeah, we’re finished with that. Off to the garage, or the tip.’ In some cases, you taped over stuff.

“If you put the tape on the machine in order to get the information off it that’s 30 years old, and you do it without baking the tape first, the oxide from the tape can come off while you’re spinning it. So you bake the tapes for at least one round, and then you can see what condition they’re in. It’s a process, and finding somebody who could actually do it was hard.”

The task of remixing and remastering the freshly baked, unearthed tracks fell to multiple ARIA Award-winning producer Wayne Connolly (Engineer of the Year three times, and Producer of the Year in 2007), Kennedy’s bandmate in Knievel and the former vocalist/lead guitarist in Nineties band The Welcome Mat.

“It was a dream for any of this stuff to get a vinyl reissue, because I just didn’t think it would,” says Kennedy. “I got some funding, and Wayne, who I’ve had a working relationship with for 30 years and is one of the country’s best producers, agreed to do it.

“It was really great being able to refresh the old stuff that’s been out before, but also this ‘new’ old stuff that stands up and also reveals a band that, despite the fact that we weren’t as successful as some, were working really hard at the craft.

“Wayne’s rough mixes of songs are often as good as many people’s full productions, because he’s got great instincts, he’s so experienced and he knows where to place everything pretty quickly, and doesn’t really see the benefit in over-fussing.

“I wanted to know what an experienced outsider’s take on it would be, and wanted it to sound like a good band in the room. There was a real trend in physical media where classic bands would get their records remixed to update their sound, but now people want warm, analogue sounds. So we didn’t want to mess with it too much.”

Nineties Nostalgia

In terms of the Nineties now being looked back upon with the same kind of rose-coloured nostalgia as other bygone decades, Kennedy has mixed feelings.

“You never think that you’re gonna be in that position, and then you get older and you are in that position. Whatever you do, there’s people coming up behind you. I can’t really speak to what that even means. When I see it, it makes me feel uneasy, and I’m not entirely sure why.

“Maybe Nineties nostalgia is here to stay, but I’m completely divorced from it because it’s completely different to being there. [Big Heavy Stuff] weren’t Nirvana, we weren’t even You Am I, but we did what we could and we did some great stuff. Our experience of the Nineties was turning up to practice every week and working on those songs, and then touring.”

Big Heavy Stuff scored several support slots other bands would’ve killed for at the time, including jaunts with the Stone Roses, Powderfinger, and Radiohead (Kennedy remembers watching the band in Sydney, realising part-way through that he was standing next to Anthony Kiedis from Red Hot Chili Peppers). It presented the band with a front-row seat to bands facing the double-edged sword of becoming huge in a relatively short period of time, and at a relatively young age.

“Radiohead and Powderfinger were both exploding, and seeing what that was like firsthand, and seeing how they handled that, was really interesting, because there were parallels in those two bands in terms of how they coped. And it looked hard to cope with,” says Kennedy. “That was really conflicting for us, because part of us wanted that as well, and part of us also couldn’t understand why we couldn’t get there.

“Now with the perspective that we have now, we feel in a way that we dodged a bullet. I think we liked the idea of being rock stars, but the reality that we saw touring – with those bands in particular – was different to what we thought. My whole career I’ve been a bit of an onlooker with that stuff, and going, ‘I don’t know if that’s for me.’ It really fucks with your head at that age because it’s like, ‘Hang on, I’ve been aiming for this for years, and now there’s potential, and I’m kind of hesitant. Why am I pulling back from this all of a sudden?’”

Although Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke has been transparent over the decades about how the onrush of extreme fame negatively impacted his mental health, Kennedy got to witness Yorke’s fragile state up close while on tour with the Oxford band.

“On the last night of the Radiohead tour, me and Eliot made it a point to go into [Radiohead’s] dressing room and say thank you, which we did. But Thom was kind of in the fetal position on the couch, and he was smoking a joint, and he was completely out of his mind. They were filming footage on the tour for a documentary [1998’s Meeting People Is Easy] where they were painted as musicians struggling with the place that they were at at the time. It’s hard to navigate all that when you’re in your twenties.”

The biggest casualty of the “too famous too soon” curse during the Nineties was, famously, Nirvana, a band who many like to point to when referencing icons that shaped and defined that particular decade. I ask Kennedy if the pervading myth of Nirvana’s seismic impact on music is accurate from the vantage point of an Australian musician in the Nineties.

“That’s a really interesting question, because it never gets asked. It’s only told as the myth that that’s what it was like,” says Kennedy. “Most of us in Newtown had a copy of [Nirvana debut] Bleach, and we also had a copy of Superfuzz Bigmuff by Mudhoney, and it didn’t feel like anything was bubbling necessarily.

“There was a bit of a change with American college rock – Throwing Muses and Pixies, who were obviously an influence on Nirvana. When Nevermind came out, it was just a great record, but there were a lot of great records that came out at that time.

“The impact it had was in sales. Initially it had a good impact in how it exposed people to independent music, and Cobain kind of made it his mission to make sure that people heard that. But it also led to watered down versions as it always does, like Creed – the same way that Jeff Buckley led to Coldplay, Joy Division led to Interpol, or whatever.

“So, a lot’s been made of [Nirvana causing] a seismic shift and all that sort of stuff, and it was huge, but I don’t know. One of the reasons we got to play [1995 single] ‘Birthday’ on Denton on Channel 7 could have been attributed to that [seismic shift]. But it’s all of a piece really, isn’t it? If you’re a Martian and you come down to Earth, is Nirvana really any different from Boston when they released “More Than a Feeling”? Nirvana used to say that too. It’s all just marketing.”

Although Kennedy seems loath to romanticise the past, the picture he paints is an appealing one, speaking of a time when it was cheap to live in the city, boredom drove creativity, and making music with your mates was what you lived for.

“The Nineties, of course it’s gone, it’s not to be repeated. And so many eras get reimagined. And I guess that’s just for someone else who wasn’t there to do, because we all had our own experiences of it,” he says. “The story of it, for me, is our tribe was together creating stuff, and it was a good time for us. We could afford to live on not much.

“That’s something I wish younger people got to experience, and I know they can’t now, and that does actually make me sad because it’s not even considered to be a thing.

“We were bored for long stretches back then, and that’s what drove us to create. I can’t imagine being young and trying to create now when so many things are going straight into your head all the time. I get nostalgic for feeling bored. I make sure that there are moments in a day or a week where I am bored, to just stay with it, because I think it’s important. Boredom is valuable because it allows you to tap into other parts of yourself that are usually shattered down by just living your life.”

The Beat Goes On

Although there’s been just as much time looking forward as back – Kennedy and Fish’s band with Josh Morris, The Electorate, have just released their second album, By Design – there’s still some more unearthing to do, with a deluxe reissue of 1997 second album Maximum Sincere, packed with more unheard tracks, due out before year’s end.

“Despite what it might have looked like, because we might have been slicker than the average band, I think that era was defined for Big Heavy Stuff in that we weren’t totally interested in becoming a mainstream band,” says Kennedy.

“We were interested in doing songs to the best of our ability, and the Nineties was where we could indulge ourselves in doing that. That might have had something to do with Nirvana generating the kind of interest within the mainstream and therefore giving us opportunity from various industrial sectors, but that’s what we wanted.

“We had no ability to navigate the industry, and we weren’t interested in impressing people who could give us a leg up. We got management because that was less shit that people in the band had to do, so we could do more music. And that was the most important thing to us, so now we’re presenting these reissues as a window into what we were doing, because it was only a limited view that you got before this. I feel good about that.”

Big Heavy Stuff’s Bruises is out now on double vinyl, CD and cassette.