One day in 2009, George Baer Wallace was at the New York City apartment of J.D. Martignon, the onetime owner of Midnight Records. The Chelsea storefront, known for its stellar bootlegs section, had closed several years earlier, but Martignon still sold records out of his apartment. Wallace began rifling through his friend’s “employee stack,” a pile of records next to the stereo that the former staff used to play at the store. He came across Lotti Golden’s 1969 debut, Motor-Cycle, an album neither were familiar with, and gave it a spin.

Motor-Cycle showed a teenage powerhouse basking in R&B-inflected harmonies and the gritty sensibility of her native New York. Released on Atlantic Records, it was Golden’s only album before falling into obscurity. Hearing it, Wallace and Martignon were stunned. “We just sat there and listened to the first side of the record almost in silence,” Wallace tells Rolling Stone. “We were like, ‘What’s that?’ It was totally strange and mind-blowing and magical. Slowly we realized, ‘OK, there are people that have been waiting for the world to catch up to them. We need to put this record out.’”

They formed High Moon Records to do just that in 2010, specializing in reissuing rarities and cult favorites. They started by releasing Love’s lost 1973 album Black Beauty, followed by the L.A. psychedelic band’s final album, 1974’s Reel to Real, and former Byrds singer Gene Clark’s 1977 solo LP Two Sides to Every Story.

Wallace, who discovered many of these artists in his twenties, made it his mission to bring these “off-the-beaten-path musicians” back into public consciousness. “I started discovering that there is this whole other world of musicians that in the pre-internet, early Nineties, were not known to most people,” he says. “Gram Parsons, Alex Chilton and Big Star, Gene Clark, Love. These were secret treasures. Each time I would discover a new one, it felt like this revelation. ‘Wait, why haven’t I heard this before? Why aren’t these people as big as the Beatles and the Stones?’”

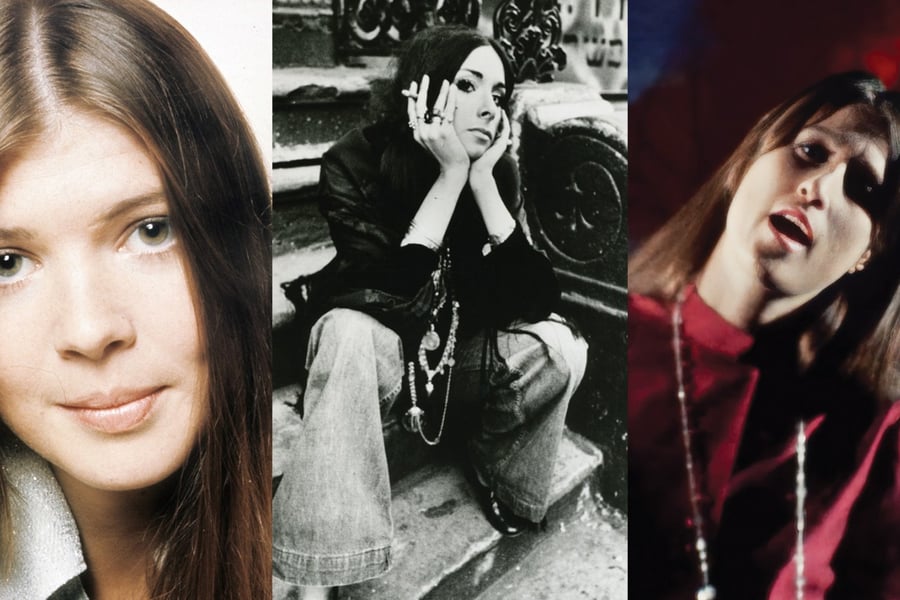

In late March, 14 years after Wallace and Martignon discovered it, High Moon finally released Golden’s Motor-Cycle. It was a lengthy process, continuing after Martignon’s death in 2016, but its timing was perfect. The reissue this year follows two other High Moon gems by forgotten female artists: Sixties San Francisco singer Jeannie Piersol and singer-songwriter-era act Laurie Styvers. Helming these two releases is Alec Palao, a producer, archivist, musician, and, according to Wallace, “the sharer of all essential music. The stuff that he finds and brings to labels like mine, it’s unbelievable.”

The British-born Palao, who now resides in San Francisco’s Bay Area, describes himself as a “quasi Alan Lomax type,” who’s been in the reissue business for roughly 30 years (he assisted Rhino with their Nuggets reissues in the late Nineties). Palao immerses himself in every project, finding the tapes, digitizing them, writing the liner notes, selecting photos, and so on. “I like to get right down and dirty with the actual nuts and bolts of how these records were made,” he says. “It’s always a thrill to be able to present it, feeling that you’ve done the most you can.”

A lover of Sixties garage rock, Palao first worked with High Moon on a Sons of Adam collection (2022’s Saturday’s Sons: The Complete Recordings 1964-1966), and on the recent Sly and the Family Stone live album The First Family: Live at Winchester Cathedral 1967. But the Styvers project was personal to him: he was close with her producer, Shel Talmy, known for his work with the Kinks and the Who.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Talmy had given all of his tapes to Palao before he died last year, and Palao passed time in the pandemic by going through his entire collection. He was vaguely familiar with Styvers, but hadn’t spent much time with her two albums, 1972’s Spilt Milk and 1973’s The Colorado Kid. He was floored by her voice — a laid-back alto that sounds like a blueprint for today’s indie songwriter Weyes Blood — and the intricate arrangements. “I love finding something that hasn’t had a light shone on it for so long,” he says. “A lot of people would say, ‘Well, I can find her records for five bucks on Discogs, so she can’t be important.’ It was that sort of attitude.”

Styvers was born in Texas in 1951, but spent her teenage years in Swinging London, joining the psychedelic folk band Justine. She moved back to the States, attending the University of Colorado, before heading back to the U.K. There, she cut her solo albums under Hush Productions, owned by Talmy and producer Hugh Murphy, whom Styvers briefly dated. “A lot of her songs are about him,” Palao says. “She really wore her heart on her sleeve.”

But little is known about her later life, which she spent in Texas with her father rescuing animals, before she died of hepatitis in 1998. “Her obit didn’t even mention anything about her music career,” Palao notes. These gaps in the timeline proved to be a challenge for Palao, especially when he was writing the liner notes and had difficulty contacting her family, only hearing from her nephew. “It’s like her family didn’t want to know,” he says. “Every request I made fell on deaf ears. I was desperate to get more information. But at the same time, her music is not complicated.”

He’s right: Split Milk is one of the lost jewels of the singer-songwriter era, a piano-driven album that radiates in the warmth of its songs. “The juxtaposition of that American songwriting sensibility with the British production and arrangements really pushes my button,” Palao says. The opener, “Beat the Reaper,” tells the story of a weekend getaway in the woods, “smokin’ or drinkin’ or playin′ guitars.” It’s a favorite of Pavement’s Stephen Malkmus, but at the time, others weren’t so taken with the album.

“Normally, I ignore records as rightfully obscure as this one,” critic Robert Christgau wrote in a scathing review at the time of its original release; it was one of the few albums he gave a grade of “E,” reserved for records that “are frequently cited as proof that there is no God.” Though Styvers was based in London, he described her as an “L.A. airhead,” who was “so trite and pretty-poo in her fashionably troubled adolescence that you hope she chokes on her own money … Oh shut up, Laurie.”

One wonders what might have happened had the reviews been more positive, and Styvers continued making music beyond her next album, The Colorado Kid. But Palao’s stunning, comprehensive reissues through High Moon — 2023’s Gemini Girl: The Complete Hush Recordings and 2024’s Let Me Comfort You: The Hush Rarities — give Styvers the moment she deserves.

JEANNIE PIERSOL IS NOW 85, living in Sonoma County. When she received a call from Palao, inquiring about music she made well over 50 years ago, she was puzzled. “I said, ‘Who are you, and why are you calling?’” she tells Rolling Stone. But Palao came to visit Piersol and her husband, Bill, and they hit it off. “He’s British, and he doesn’t drink,” she says. “He just drinks tea. We had a great time.”

Though Piersol was only briefly in the music scene, it was during one of its most legendary eras: the very trippy mid-Sixties in San Francisco. “She’s right of that generation, your Airplanes and your Deads,” Palao says. Piersol was close with Grace Slick growing up, briefly joining Slick’s group the Great Society (alongside Slick’s husband Jerry, her brother-in-law Darby, and others). Piersol went off on her own, fronting bands the Yellow Brick Road and Hair, and playing storied San Francisco venues like the Fillmore, the Avalon Ballroom, and the Matrix.

Piersol got a solo deal with Cadet Concept, a subsidiary of the famed Chess Records, and flew to Chicago to record several sessions with Earth, Wind & Fire’s Maurice White, guitarist Phil Upchurch, and producer Charles Stepney. “The absolute dream team,” Palao says. “This is Chess at its absolute peak, as far as that studio sound was concerned.”

A pre-fame Minnie Riperton, then a secretary at Chess, even supplied backing vocals. “She and I became friends,” Piersol says. “I made her some clothes. She liked my mini skirt. I made her a mini skirt. They didn’t invite her to dinner, and I was really pissed at that. I said, ‘Minnie, you’ll succeed and they’ll all be sorry.’ And that’s exactly what happened.”

On songs like “The Nest” and “Gladys,” Piersol’s voice was hypnotic, using a musical palette that dabbled in psychedelia, R&B, and Indian influences. “It’s this wonderful juxtaposition of a San Francisco hippie chick who loves R&B,” Palao says. “It sounds like a more soulful Grace.” But her music went nowhere, and she eventually got pregnant and left the industry. Asked about her later life, Piersol is utterly charming and sarcastic. “Three kids and that should say it all, really,” she says. “You have these kids, they ruin your life. I never thought about the music.”

High Moon’s Piersol anthology, 2025’s The Nest, chronicles her brief career, containing outtakes, demos, and live performances. Palao says it was a trickier process compared to the Styvers project — Piersol’s Chess tapes are believed to have burned in the 2008 Universal Studios fire — but he was able to cull from tapes that belonged to the late Ray Anderson, a longtime figure in the San Francisco scene. Piersol was grateful for Palao’s extensive work on the project. “I just wish I could [still] wear mini skirts,” she jokes.

When music fans discover cult favorites from previous decades — particularly female artists — they’re often compared to others. Golden is usually compared to Laura Nyro, while Styvers is put side-by-side with Carole King and the lost California songwriter Judee Sill. “These singer-songwriters are so unique, amazing, and singular, and it’s a little frustrating,” Wallace says. “You want to run up to the rooftops and shout out to the world, ‘Hey everybody, listen to Jeannie Piersol and Lotti Golden and Laurie Styvers!’ But when an artist is of no-name recognition, it’s so hard to get them up to the level of being known.”

In an era where physical media is increasingly fading, it’s incredible that these collections exist at all. “High Moon is like a miracle,” Palao says. “The fact that they’re still around to do these deluxe packages or allow me to curate something — all power and loyalty to them. They really care. And I can absolutely tell you it’s not about making a profit.” As Wallace says, “We put every fiber of our being into these. You can’t hold, touch, or feel a stream of music.”

From Rolling Stone US