When I was pregnant with my daughter, I held inside me a collection of cells that could live to the year 2150. I held in my womb my daughter Magnolia, whose tiny eggs were already formed. If one of them went on to grow inside her, and that person grew up to age 80, within me lived a 200-year life span. This information charged me with a direct line to the future. A future which, when I have the courage to peer into the gut-aching truth waiting for me — at the bottom of the pile of unfolded washing, of unanswered emails — demands action.

On current projection, by the year 2150, New York and London will be mostly underwater; the Netherlands, too. All of Bangladesh and Kolkata, all of the south of Thailand. The Tiwi Islands and a good majority of Papua New Guinea. The edges of Sydney and the heart of Melbourne, submerged.

At 3°C of warming, scientists predict the world could pass several catastrophic points of no return, from the runaway melting of ice sheets to the Amazon rainforest drying out. “Present trends are racing our planet down a dead-end 3°C temperature rise,” says U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres. “The emissions gap is more like an emissions canyon.”

The U.N. International Organisation for Migration has cited estimates of as many as one billion environmental migrants in the next 30 years, while more recent projections point to 1.2 billion by 2050, and 1.4 billion by 2060. After 2050, that figure is expected to soar as the world heats further and the global population rises to its predicted peak in the mid 2060s.

I swing between absorbing this information as if it were a Disney film — 10 years to save the world; delusional, warfaring old men wielding power; the patriarchy hanging on by a thread; young people and women rising up, but maybe not in time; who will save us — and a seriously dire eulogy for the future and the planet that I know and love.

Lapping at this global dilemma is the rising cost of rent, the financial impossibility of home ownership, $2.90 cucumbers and $7 milk, and the constant dripping away of the dream we were sold as kids. Work hard and you’ll have a house, a family, clean water and a stable world. It’s a lot to wrap your head around, but when you dig deep and start asking questions, it’s all terribly and frighteningly related.

We are living in the decisive decade. Scientists say we have until 2030 to cut global emissions by 75 per cent to stay under 1.5°C of warming, and cut them by 100 per cent by 2050 to avoid 3°C-plus of warming. But at the rate we are going, the global carbon budget will be fully spent in 2.5 years from now. Meeting this target would need a five-fold increase in global pledges. The latest IPCC report says that “exceeding 1.5°C is virtually inevitable”.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Meeting these targets requires unprecedented global efforts and transformative changes across various sectors: energy, transportation, agriculture and industry. The most direct way to do the impossible? Policy. What does policy rely on? Politicians and governments. Politicians and governments who care about maintaining a secure existence for humans. Politicians who actually consider the planet that feeds, clothes and hosts them.

2022 Lismore floods

The state of play

Here in Australia, we spin in the hamster wheel of a three-year electoral cycle. As quickly as things come together, they can fall apart. As quickly as leaders are elected, they are planning for election once again. This isn’t all doom and gloom; it means that politicians are alert to the temperature of the times — if only they could feel it.

For young people, the 2024/25 election will be fought on the battlegrounds of the cost of living; for older generations, on wealth protection. And frankly, for many over-65s, this means hanging onto fossil fuels by the commas in their dividends.

So when does the end of the world become a matter for federal policy, what role might it play in the election, and what’s stopping us from enacting the change that is so clearly needed?

Australia is one of the world’s largest producers of fossil fuels. Our climate action ranks in the bottom 10 countries assessed in the Climate Change Performance Index. While national emissions have seen a dip of 24.7 per cent from 2005 levels, per capita emissions still soar above the OECD average. With a mere six years to chop off another 19 per cent to meet Labor’s 43 per cent reduction target, the nation teeters on the edge of climate catastrophe. The trajectory of our current policies has us on a path to 3°C.

Labor’s heralded Climate Change Bill 2022 sets out a target of 43 per cent reduction from 2005 levels by 2030 and net zero by 2050. Labor’s newly introduced Safeguard Mechanism requires Australia’s highest greenhouse gas emitting facilities to adhere to the above targets, or pay for carbon credits. But put into practice, these bills are weak. Paradoxically, the Labor Government supports growth in fossil fuel production and export, with 116 new coal and gas projects expected to begin production before 2030, despite clear statements from the United Nations and the International Energy Agency (IEA) that new fossil fuel projects are incompatible with global temperature goals. Labor are also yet to make good on their promise to overhaul the country’s environment laws (the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act), and there are plans to transfer approval of offshore gas projects to the Resources Minister, taking deep sea projects off the desk of Tanya Plibersek for good.

While the cogs of Canberra grind slowly, it’s clear that Australians want change. Three million houses have solar panels on their rooftops — more than 40 per cent of the electricity in our main national grid is already being met by clean sources of power. The 2022 election proved that Australians want rapid political change in the climate sphere, even if the government they voted in on that basis seems to forget this.

With billionaires like Gina Rhinehart donating millions to the Liberal party each year, and fossil fuel companies donating at least $2 million of disclosed donations to both major parties, is it actually possible to think we could phase out fossil fuel projects?

To understand how to overcome this zero sum game, I sat down with some of the people working in the belly of the beast, agitating for action.

Senator David Pocock

Changing the game

Senator David Pocock told me, in characteristically plain speak, “We need legislated emission targets that are actually in line with the science.”

And he’s right. If we’ve learnt anything from the past few years, it would be to follow the science.

To make laws according to science, Australia needs to legislate 75 per cent emissions reduction by 2030, and 100 per cent emissions reduction by 2050. This means Net Zero by 2050, and that’s coming late to the party.

Australian climate scientist Lesley Hughes says that we actually need Net Zero by 2040 to keep warming below 2°C. She said, “The single most important policy that Labor could take to the next election would be to cease approving new and extended fossil fuel developments. Every one of these adds to the damage being inflicted on our children’s future.”

For such rapid and radical change to occur, we need both major parties to commit to these reductions. In the words of Matt Kean, ex-NSW Minister for Climate and Energy, “What we need, more than ever, is political leaders who have conviction in Australia’s renewable energy opportunity, who have the courage to do what’s right, and the humility to reach across the aisle and build a broad consensus. This is in our national interest.”

There is a strong history of bipartisanship resulting in positive policy, like the Racial Discrimination Act and the National Agenda for a Multicultural Australia. Seems like a while ago? Consider the Stage Three tax cuts, brought in during 2022 and due to take effect in July of this year. Although the policy was substantially amended by Labor, this is a piece of work handed between two parties across terms.

“Everyone was saying, ‘It’s going to be politically unfeasible to walk back any of those changes’,” says Pocock. For him, the key is focusing on — and believing in — the end goal.

“The tendency to think about what is achievable as the starting point is actually giving power to the fossil fuel industry. Instead, we’ve got to say, ‘What do we need for the country?’ and push for it, not simply ask, ‘What will be achievable?’. Because what will be achievable will stretch if you’ve pushed for more in the first place,” he says. “Big things change in short periods of time.”

If it seems naive to liken Stage Three tax cuts to far-ranging climate policy — which requires upending both the production and infrastructure of our energy consumption — you need only look at Germany. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Germany’s supply of fossil fuels was majorly disrupted, driving up wholesale energy prices and, in turn, threatening industry and the economic wellbeing of its citizens.

Rather than maintaining the status quo — and descending into crippling recession — Germany (Europe’s largest energy consumer) supercharged its renewable transition. In 2023, the country generated more than half of its electricity through renewables. While, admittedly, the country had a short-term increase in fossil fuels to aid with the sudden hit on their power supply, Germany aims to be 80 per cent renewables by 2030 and be mostly decarbonised by 2035.

How have they done it? Through decreasing energy consumption and increasing renewable production. The government tasked individuals, businesses and state entities with reducing usage of gas, resulting in an 18 per cent drop, while increasing generation of wind, solar and hydropower.

To shield the economic impact of the increase in wholesale energy, the government rolled out a series of relief packages, subsidising gas and electricity — without incentivising fossil fuel use.

Any debate about climate policy comes down to cost; investment in production and infrastructure, transitioning to all-electric homes and businesses, and the hit to investment incomes. And all of this is surmountable.

With returns from renewables beating fossil fuels three times over since 2010, divesting from fossil fuels isn’t just altruistic, it’s fiscally prudent. When it comes to financing large-scale electrification, SwitchedOn proposes the Electrify Everything Loan Scheme (EELS), which Pocock has included in his 2024/25 pre-budget submission. This HECS-style scheme, which covers the cost of homeowners implementing solar, batteries and electric appliances, results in households saving on energy bills while costing the government just six per cent of the funds loaned. If 80 per cent of Australian homes took the government up on its offer, the hit to the budget would be $10.4 billion — the same amount spent yearly on the fuel tax credit, which cuts the cost of diesel for mining trucks.

All-electric homes would see a significant drop in energy bills, even potential credits, which would be a welcome reprieve for struggling households who have experienced increases in energy prices of 40 per cent over the past two years.

In the longer term, the financial upside could also be realised in home insurance premiums, which have increased in part due to large losses from recent severe weather events.

Meanwhile, the sleeping giant in Australia’s energy policy picture is our laughably low taxes on the gas industry. Australia is the largest exporter of gas in the world, yet we barely skim the surface when it comes to taxing the companies taking our gas offshore and selling it for trillions. Since 1996, Norway has been taxing the profits of its oil and gas sector at 78 per cent, while we subsidise our gas industry. Proper taxation of the gas industry could fund electrification projects nation-wide, future-proofing our country for the economic weather to come.

In a sea of statistics, scientific nomenclature and euphemisms, climate lawyer Isabelle Reinecke puts it clearly to me. “Until we actually can say, loudly and strongly as a country, ‘We need to drive down emissions by this much, by this state, and we are going to hold ourselves accountable to doing that’, there’s no way in the world that we can drive down emissions fast enough. The public needs to understand what we need, and then how we do it is simple. You shut down fossil fuels, you stop subsidising the fossil fuel industry. You stop the concept of offsets being a way to save the planet. You electrify everything.”

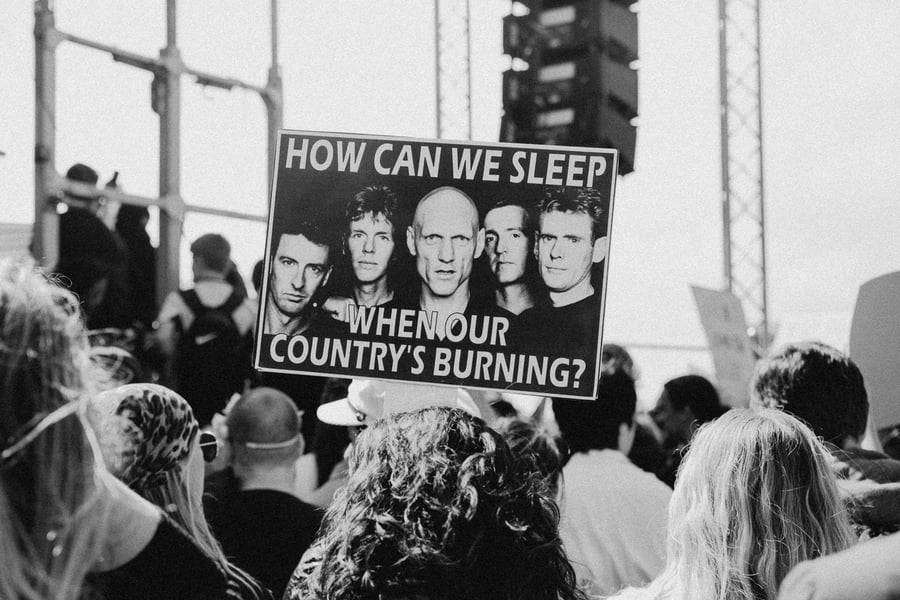

2022 climate strikes

How can we make change happen?

Visionaries aside, political action is driven by the fear of not being re-elected. Voters must make it known that they want the climate and energy policy that is going to save their lives in the long term and make life financially easier in the short term.

The major parties can feel this pressure two ways. They either hear noise directly from the public, or they lose their seat to an Independent, the Greens or another minor party.

This is what happened at the 2022 election — voters sent a clear message to the Coalition by voting six independents into Liberal Party blue-ribbon seats. In the ACT, David Pocock made history by being the first ever Independent to take one of the two tightly-held Senate seats. This sea of Teal in the middle of the major parties has seen more climate legislation tabled than ever before, and allowed forward-thinking climate policy and renewable energy to claim political buying power. With another election, many hope that power will increase.

Earlier this year, Pocock introduced his Duty of Care Bill, which posits that any new fossil fuel projects should be assessed against the climate impact on future generations. Although it might not pass a Private Senator’s Bill (the major parties selfishly only pass their own legislation), it has tabled the issue nationally once again.

Independent Senator Jacqui Lambie has pushed constantly for the creation of a fourth branch of Defence to respond to natural disasters, examining the real world impacts of climate change through a practical lens after countless disasters have impacted the country. In 2024, this concept may gain ground.

Looking ahead to the next election, what message will the public send the federal Labor government? Will it be a clarion call to climate action? Pocock hopes so.

“They may be better than Scott Morrison’s government, but what about our kids? What about our future? Can they actually deliver in line with what Australians want? And if they don’t, I would hope that people vote for politicians who are going to stand up for their community. We’ve seen that time and time again in [Parliament], with the cross bench at every opportunity pushing for climate ambition.”

As my now one-year-old daughter grasps for the keyboard as I try to finish writing this piece, I can’t help but hope that everything I choose to do with my hands and mind in this life will edge closer to making something better for her, for us, for future generations who weren’t in power or able to vote in the decisive decade.

We are now at the point where we, as a species, need to think bigger than we have ever thought before. We must be incredibly decisive, irrevocably collaborative and, above all, we must believe that we have some kind of chance of changing our behaviour. We have to put old divides behind us if we are to survive together. We must radically change policies and the rate at which they are implemented. We need vision, ambition and action from our politicians, and it’s up to us to remind them who they serve, what we want, and to hold them to account.

Jack River performing live

This article features in the June-August 2024 issue of Rolling Stone AU/NZ. If you’re eager to get your hands on it, then now is the time to sign up for a subscription.

Whether you’re a fan of music, you’re a supporter of the local music scene, or you enjoy the thrill of print and long form journalism, then Rolling Stone AU/NZ is exactly what you need. Click the link below for more information regarding a magazine subscription.