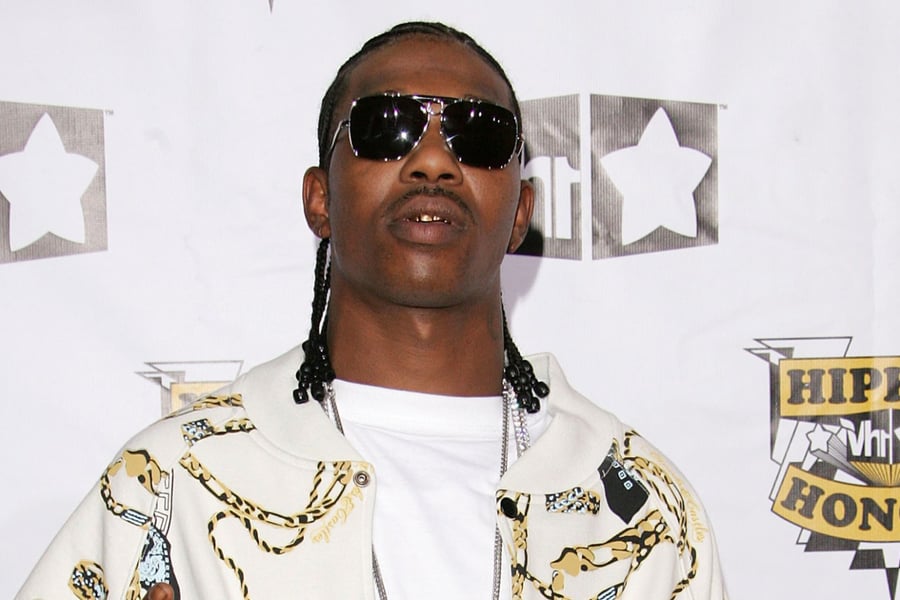

On July 2, U.S. District Judge Susie Morgan ruled that B.G. must turn in his written lyrics to the government before releasing them. The ruling is the latest setback the rapper born Christopher Dorsey has faced since he was sentenced in 2012 to 14 years in federal prison for felony gun possession and witness tampering. After earning his release last summer, B.G. — known for his inimitable New Orleans twang and songs like “Bling Bling,” “Cash Money Is an Army,” and “Don’t Talk to Me” — was arrested in March for violating parole, following a performance with the rapper Boosie, who’s also been convicted of a felony.

Prosecutors later formally proposed that B.G. submit his lyrics to be approved by Louisiana prosecutors or face tighter parole restrictions; they reportedly want B.G. to refrain “from promoting and glorifying future gun violence/murder” and expressing anti-“snitch” sentiment in his lyrics. During a June hearing, federal prosecutor Maurice Landrieu said, “at some point in time, we have to try to stop this cycle. We’ve become numb to it, and that doesn’t say much for any of us.”

New Orleans has historically had one of the highest murder rates in the nation. In 2022, the city had the highest rate in the country, though it dropped 40 percent in 2023. But these ills aren’t B.G.’s fault. The violence Landrieu references isn’t a product of rap, but poverty; censoring B.G.’s music is unlikely to put a dent in New Orleans’ violent crime rate.

The ruling represents the latest low in the justice system’s continued persecution of rap music. For years, rap has been scapegoated by opportunistic politicians and media personalities looking to virtue signal (if not dog whistle to their followers) by condemning a Black art form. But in recent years, prosecutors all over the country have taken things a step further by using rap lyrics as evidence in court cases. Soapboxing is one thing; warehousing is another. (The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Louisana declined to comment for this story.)

In 2021, Maryland rapper Lawrence Montague was sentenced to 50 years for a host of charges after a state appeals court ruled that a rhyme that was recorded over a jail phone was “so akin to the alleged crime that they serve as ‘direct proof.’” Numerous rap lyrics have been referenced in state and federal indictments, including in the high-profile YSL case. And now, with Morgan’s rulings, prosecutors are seeking to police lyrics before they’re even released. It’s a subtle implication that rap itself can be akin to a criminal act.

B.G. grew up in the 13th Ward of New Orleans, a city that reported one of the country’s highest poverty rates in 2022, at 22.9 percent. That kind of upbringing breeds the crime he depicts in his extensive catalog. It’s also a leading factor for addiction, which he’s been open about grappling with. Despite his tumultuous upbringing, B.G. carved a considerable legacy in rap through 10 albums and his work with the Hot Boys, who recently announced a reunion tour. But now, his catalog will be supervised by the whims of a prosecutor for the duration of his parole.

Nola.com reported that during the June hearing, Landrieu “argued that Dorsey’s lyrics have carried leaden weight on New Orleans streets.” He also said, “I don’t think it’s too much to ask for a limited period for him to stop saying certain things.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

During the hearing, B.G. told the judge, “I just feel like Christopher Dorsey and ‘B.G.’ are two different people,” arguing that “[the ruling is] basically like telling Robert DeNiro he can’t make any mob movies. I just did a hard 12½ years … In no way am I glorifying. I’m just being creative, from coming up in a messed-up environment. I’m just rapping about what I know.”

In August 2023, Louisiana became just the second state to enact the Restoring Artistic Protection Act, which limits a prosecutor’s ability to use rap lyrics against artists — but the state’s legal system still has a long way to go to become racially equitable. A 2023 Southern Poverty Law Center Action Fund report concluded that just four of Louisiana’s 64 sheriffs are Black, and only 12 percent of its 42 district attorneys are Black. That dovetails with the second-highest incarceration rate in America, with Black people being 3.8 more likely than white people to be sentenced.

Last year, the Heritage Foundation unveiled Project 2025, an 887-page policy road map that was co-authored by many Trump administration officials, and which Foundation describes as “the conservative movement’s unified effort to be ready for the next conservative administration to govern at 12:00 noon, January 20, 2025.” Though unrelated to the project, this bid for state-controlled rap feels like it’s in lockstep with its regressive fantasies.

In 2021, lawyer Alex Spiro told Complex that, “when prosecutors get convictions based on one kind of evidence, prosecutors tend to repeat business. If they do something that’s effective at combating crime or getting a conviction, they’re likely to repeat it, if nobody calls them out on it. And that’s why it’s important to push back on the system and to ask hard questions and to examine these matters.” The same can be true of draconian parole measures.

For B.G., merely performing with an artist who’s been convicted of a felony has re-incarcerated him. And now, releasing an unapproved song could. Is he essentially federally barred from doing radio freestyles?

In March, the rapper took to his Instagram to post that, “it’s crazy how after paying my debt to society with 12½ years of my life, I come home and still ain’t free. I been doing everything the right way, and it seems like that ain’t enough. I been going [through] it behind the scenes and got a muzzle on for the time being, but I’m confident I’ll come out on top. I always do.” Hopefully, he’ll be able to release the music he wants and be the symbol of resilience that he’s always been. But it’s not an obstacle he, or any artist, should be dealing with.

The next prosecutor in control of a rapper’s freedom can now cite Morgan’s ruling, setting the stage for the justice system to become an arbiter of what’s acceptable in rap lyrics. In the 1990s, 2 Live Crew had to fight against having their lyrics being banned by the government for being too explicit. A record-store owner was arrested for selling the music, as were two members of the group for performing it. Today, artists like Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion are pop stars with the same raunchy lyrics that the government would have liked to ban.

If we conceded the power to greenlight only the lyrics the government sees fit, rap wouldn’t be where it is today. That’s why it doesn’t deserve the power to do so now, and shouldn’t be using B.G.’s parole status in its efforts.

From Rolling Stone US