Coinciding with their special 50th anniversary tour, iconic Australian rock ‘n’ roll band Radio Birdman are the subject of a detailed new biography.

Written by esteemed rock music writer Murray Engleheart (Blood, Sweat and Beers: Oz Rock from The Aztecs to Rose Tattoo), was released on Tuesday, July 2nd, and received the approval of the ARIA Hall of Famers.

“Acclaimed author Murray Engleheart has written what promises to be, far and away, the most in-depth and complete history of Radio Birdman to date. Years in the making, Retaliate First is a compelling synthesis of thousands of hours of research, first-hand accounts and unique insights. It’s a must read for anyone who wants to know what really happened,” they wrote on their socials.

Engleheart’s book is drawn from more than 150 interviews with the band members, their closest associates, devotees, and observers. With 2024 marking their half-century of existence, and a commemorative tour that may be their last, it’s the perfect time to look back over fifty years of the band that never took a backward step and made rock ‘n’ roll thrilling and dangerous once more.

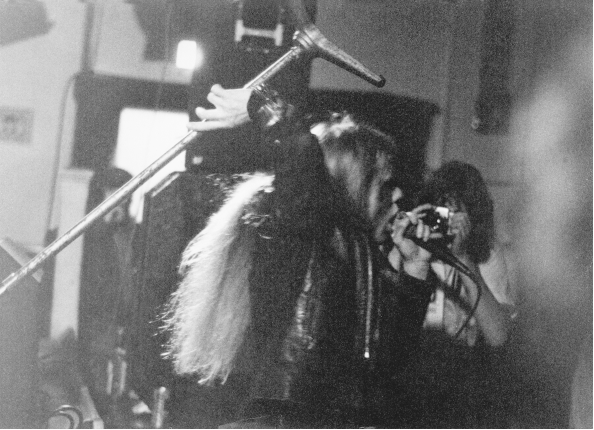

In the below excerpt from the book, we’re taken inside several seminal moments in Radio Birdman’s journey, including a chaotic Sydney show in 1977.

Radio Birdman: Retaliate First is out now via Allen & Unwin.

The wine flagon had been thrown through the closed windows of the first floor of Paddington Town Hall with almost superhuman force. It cleared the footpath in a graceful arc, trailed by a galaxy of tinkling glass, and shattered on a car parked on Oxford Street, bathing the vehicle in the last of its alcohol content. There was a near cinematic pause, as if to allow any stunned passers-by to digest what had just detonated before them; then other projectiles—anything that wasn’t bolted in place—began to rain down from on high, each incoming heralded by the sound of further smashing glass. Some fervent punters above probably even considered taking a leap of faith themselves to personally enlist in the unscripted fireworks commemorating Radio Birdman’s virtual coronation.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

The date was 12 December 1977, and without any great flourish of publicity, the ultimate in rank outsiders had pulled around two thousand rabid bodies to the cathedral-like landmark in Sydney’s eastern suburbs.

The crowd under its ten-metre ceiling was similar in number to that drawn by AC/DC to the Hordern Pavilion just a few kilometres away after returning from their successful UK and European tour exactly a year earlier.

Just three short years prior, Birdman’s personnel of five had often exceeded their audience. From there, armed with microphone stands and an equally steely self-belief, they steered toward the oncoming traffic in the local music industry, horrifying record companies, enraging bouncers, bewildering audiences, with desperate publicans reaching for the power kill switch. Their attack and defence strategy was the same: retaliate first, and second if necessary. No triggering action was ever required.

At Paddington, those hand-to-hand combative labours came to fruition, the scattering of fevered support in their earliest days having coalesced into this vast legion. But while their summit-reaching night at the town hall—which was broadcast on Radio 2JJ—was a triumph, it was a badly lacerated win, with the worship of many cloaked in dark overzealous energies, some even signing on for duty with a smearing of blood on the internal walls of the venue.

At the end of the night, almost every sheet of glass in the building was shattered. The remnants looked like macabre mouths of jagged teeth or ceremonial masks from some lost tribe. They seemed to be grinning down at the carnage as a sea of individuals poured from the building and fanned out across Oxford Street with no regard for the traffic. Any vehicular impact wouldn’t be felt for a day or two anyway. They were anaesthetised en masse, in a state of euphoria, the sound of a new world and tinnitus screeching in their ears.

Fast forward a few months and the Radios were still sparking spot fires. At first the comments by the heathens seemed lighthearted, even welcoming.

‘The Birdman is here!’ one guest declared to all at the backyard gathering in western Sydney, pointing at my band T-shirt.

Any ambiguity was soon ripped away by the more pointed directions provided by another very large attendee.

‘Fly the fuck away, little Birdman!’ the behemoth growled down with slow deliberate menace, crop-dusting my face from point-blank range.

It escalated from there and retreat soon seemed the best option. My friends and I made a swift exit from the premises, with a booming hail of beer cans beating out a broken rhythm on the body of our departing car.

To be fair, the aggressors recognised something was out of sync, that we were different. And they were right. It was as if the Radio Birdman name alone projected a challenge, a perplexing, unnerving uncertainty, even from my pale, somewhat concave chest.

………………………………………………………..

A slightly exotic-looking kid, his dark hair largely obscured by a striped beanie, was among a crowd of 14,000 basking in the glowering presence of the Rolling Stones at Detroit’s Olympia Stadium in late November 1969.

It was two in the morning when the Stones finally appeared before Deniz Tek who had classes the next day at Ann Arbor’s Huron High School, 70 kilometres west of Detroit. But for Deniz, balancing cars, girls, getting high, rock and roll and his final-year studies, although not an effortless endeavour, was certainly proving to be achievable.

Tonight, however, his tutors were the Stones, who now stood, towering well above their actual height, just metres away. Deniz had idolised founding member Brian Jones, who’d died in mysterious circumstances four months earlier, but now the young guitar player gazed up at a new messiah who had been in plain view the whole time; Keith Richards.

Three days later, the Stones tore through several performances at New York’s Madison Square Garden, which would be captured on the Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! record. Their stop in Detroit, however, had momentarily placed the English overlords in a salt-of-the-earth music scene in the state of Michigan whose broader influence, though in most cases negligible at the time, would in years to come echo around the world. In what would be later generally referred to as the ‘Detroit scene’ there was the soon-to-be ridiculously successful Grand Funk Railroad, along with Brownsville Station, the Rationals (with Scott Morgan), the Up, SRC (led by singer Scott Richardson), the Frost (with guitarist Dick Wagner at the helm), the Amboy Dukes (featuring Ted Nugent), Mitch Ryder and Detroit (including axeman Steve Hunter), and the Bob Seger System. High in that pack were the Stooges—with the wildly interactive and endlessly physically flexible singer, then known as Iggy Stooge—and the MC5.

The collective sound of these acts was the extension of Detroit’s blue-collar reputation as a major car manufacturer. Here, Ford, General Motors, Chrysler and Dodge had forged a dynasty early in the twentieth century and created the ‘Motor City’.

…………………………………………

The Hill Auditorium at the University of Michigan wasn’t even close to filling its 3500-seat capacity and many of those who did attend stayed only briefly for the pair of performances by Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable with the Velvet Underground. The excessive volume, along with the abrasion of Lou Reed’s ‘Ostrich’ guitar and the scraping electric viola of the warlock-like John Cale, usually had that effect.

Deniz Tek didn’t have the opportunity to witness the Velvets nor Jimi Hendrix and the Who when they too appeared in Ann Arbor in 1967. He was on the other side of the planet by then, courtesy of his father, a professor at the University of Michigan, who secured an exchange professorship at the University of New South Wales.

While the Masters Apprentices, the Loved Ones and the Easybeats sounded marvellous pouring from the radio in Sydney, the Doors’ ‘Light My Fire’ was a cascade to somewhere darker and very different. The self-titled LP from which it was lifted was a mix of slithering menace and ethereal poetry, jazz flourishes and baroque stylings. There was the snarling urgency of ‘Break On Through’, a near-obscene animalised reading of the Howlin’ Wolf–popularised ‘Back Door Man’ (the grunting and growling of singer Jim Morrison could not have been lost on one Jim Osterberg back in Ann Arbor) and the record’s closer, more than eleven minutes of unsettling mystic hell titled ‘The End’. Like the Velvet Underground, the Doors were a dagger to the temple, with Morrison seeming to want to caress and then put out an eye.

The Tek family returned to Ann Arbor in early January 1968. Deniz quickly snapped up the Doors’ first two LPs, along with Pink Floyd’s The Piper at the Gates of Dawn and Dylan’s John Wesley Harding, its spare sound reaffirming his faith.

The FM radio revolution was now hitting its stride in America, with home-stereo quality sound aided by acts placing greater importance on albums. The local airwave gateway was WABX FM, which famously beamed from ‘high atop the David Stott Building’. Among bands Tek discovered via the station was the Velvet Underground, who, later that year, would unleash the ear-and-teeth-grinding fury of their second effort, White Light/White Heat, with its centrepiece, the seventeen-minute distortion-fest of ‘Sister Ray’. The skull tattoo on a near-black background on the front spoke volumes about how radically different the recording was to the flowery peace-and-love times.

Meanwhile, the Stones retook their rightful place in the Tek pecking order with the Beggars Banquet album and sealed the fate of Lennon and McCartney.

Deniz Tek: ‘It was pretty much over for the Beatles. The Stones were just getting started.’

As were an outfit called Alice Cooper, fronted by Detroit-born Vince Furnier. The Coopers made the Stones look positively regal, all donning a mix of offbeat op-shop clothing, with perhaps the longest hair on the scene. The outfit had been struggling in their adopted home of LA, where their sound and stage act emptied several venues, including, most famously, a club in Venice, California, called the Cheetah Room.

‘When I saw 2000 people walk out on them, I knew I had to manage them,’ Shep Gordon told Newsweek. ‘They exhibited the strongest negative force I’d ever seen.’

……………………………………………….

The American accent on Illawarra regional radio, south of Sydney, in the second week of November 1976, was striking in both tone and urgency. ‘We interrupt this program to bring you the following important message from Steve McGarrett high in the David Stott Building. Hit it!’ Deniz Tek’s voice then continued over a roaring preview of the Radios’ recorded version of the Stooges’ ‘T.V. Eye’: ‘Radio Birdman will launch a blitzkrieg attack on Steel City (Wollongong) this Friday night. Killer rock and roll jams starting at 8 pm at the Corrimal Community Hall. Tickets two dollars at the door. Lord have mercy!’

The announcement gave the impression the outfit’s position—while growing in popularity—was far loftier than it was.

With rare exceptions, Birdman had studiously torched everything behind them at virtually every turn. Even Chequers in inner Sydney, which hosted every conceivable act in the country, didn’t want the Radios—or their crowd—coming down their marble staircase, thank you very much. And there was no fucking way they were going to hang out at the Manzil Room at Kings Cross until 4 am, surrounded by industry people and every band they despised. But something had to be done.

Warwick Gilbert (Birdman bassist): ‘We had an impromptu brainstorming session with (Birdman manager) George Kringas and (fan club founder) Paul Gearside after a particularly exciting Radio Birdman gig at the Oxford (Hotel in Darlinghurst). We were just thinking of how to push it forward and came up with the idea of the “Blitzkrieg”, a series of half-a-dozen gigs with the military kind of metaphor of bombing the city, because the music was really powerful.’

The tour poster Gilbert created featured a diving German World War II Stuka bomber—an idea from the cover art for Jefferson Airplane’s After Bathing at Baxter’s record and their Fillmore West gig poster Warwick bought in his late teens—with a banner of ‘Radio Birdman Blitzkrieg’ and the now-revamped logo, which had replaced the Blue Oyster Cult symbol on the Birdvan door.

And the colours involved were critical: red and black, which were already reflected in the band’s flags and banners. The poster projected and heightened the general sense of foreignness around Radio Birdman, an intangible unknown, while the Blitzkrieg expression precisely reflected what the tour dates would be: a strategic, unforgiving lightning war on the eardrum and body in five ‘offensives’.

In an era when gig posters carried only the base textual information in one colour, the mass display of German Stukas around inner-city Sydney declaring Radio Birdman’s Blitzkrieg campaign was like an Andy Warhol art installation in wartime.

……………………………………

War wasn’t just an aesthetic for Radio Birdman—it was art imitating life, in a grouping that was a fateful collision of very different individuals. It was a highly combustible alliance but one that generated a rapturous response from fans.

Animosity would often seep into plain sight, and theatrical physical altercations on stage were anything but a mirror of the play-acting of Alice Cooper. The conflict between singer, Rob Younger and drummer, Ron Keeley was only one of the ongoing skirmishes that were completely indivisible from the music.

Penny Ward (Birdman devotee): ‘They created that music because of the conflict. It’s hell for the band but it was good for the music.’

Brad Franks (Birdman devotee): ‘You never knew whether they’d end up beating each other up on stage. There was many a night that ended in them fighting. They were so intense about the music.’

Warwick Gilbert: ‘There is a price you pay to create something like that. I think the volatility of it was its essence. I mean, without even playing a note there were sparks amongst people [within Birdman] who rubbed each other up the wrong way. Everyone did—for whatever reason—in our own unique way! The different strong personalities created a certain electricity.’

Ron Keeley: ‘It was us against the world, most definitely—but also it was us against each other from time to time. The personalities . . . could really screw it up.’

John Needham (future Birdman manager): ‘Birdman had the unique ability to take all the inner hostility and conflict they had towards each other, and just get on a stage and broadcast it; sort of deflect it out into the audience. It had a transforming effect if you were in the crowd.’

All the while, Radio Birdman hovered above the growing punk scenes of London and New York like an out-of-body experience. Not only had they been there first, drawing on the now-hip Stooges and New York Dolls, but they were a precision power machine rather than barely three chords and a snotty DIY attitude.