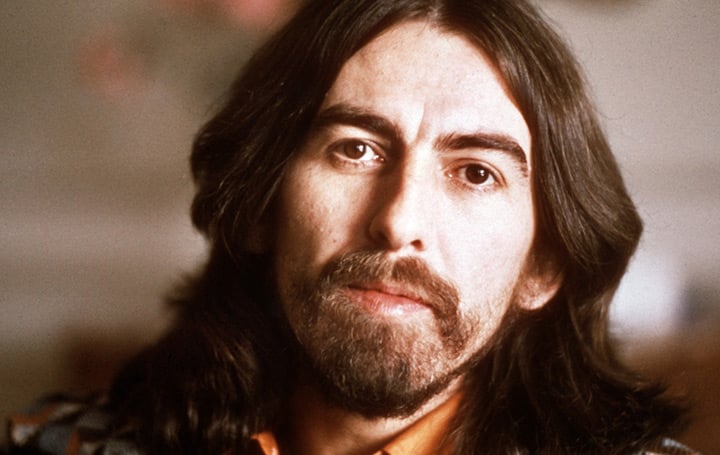

Like his father, the late Beatles guitarist George Harrison, Dhani Harrison is a musician. He made his professional debut on his dad’s last studio album, Brainwashed, issued after George’s death in 2001. Now 36, Dhani composes film scores and is half of a band, the newno2 – named after a recurring character in the late-Sixties British television show, The Prisoner – with another musical son, Paul Hicks. (His father, Tony, is the founding guitarist of the Hollies.)

Unlike his father, Dhani is – with his mother, Olivia – a caretaker. Since George’s passing, Dhani has been active in the archiving and release of his father’s solo legacy, including a 2004 box, The Dark Horse Years 1976-1992; a 2012 rarities CD, Early Takes: Volume 1; and the first comprehensive reissue of George’s early life away from the Beatles, The Apple Years 1968-1975. The centerpiece of that set – seven CDs with bonus tracks plus a DVD, issued in September – is, of course, the 1970 masterpiece, All Things Must Pass.

But The Apple Years begins with George’s initial, eccentric excursions – the 1968 Indo-rock film score, Wonderwall; the ’69 Moog holiday, Electronic Sound – and runs through the focused spirituality of 1973’s Living in the Material World and the understated-R&B writing and meditation on 1974’s Dark Horse and ’75’s Extra Texture (Read All About It). “I’ve been dying to get to this for about ten years,” Dhani claims. “There were some things record companies had done over the years. My dad had already remastered All Things [for a 2001 reissue]. But no one was doing Electronic Sound.”

When Dhani and I spoke for a recent news story about the new box in Rolling Stone US, we covered more ground than space allowed. What follows is a longer, deeper walk through the opening chapters of George Harrison’s career apart from and beyond the biggest band in pop history. Dhani says Wonderwall is his favorite album in the set and admits he is still surprised by his father’s music – even records as familiar as the sonically opulent All Things Must Pass. “I was trying to work out some chords for one of those songs,” Dhani says. “And I realized that you can’t hear the chords in there – because there are 50 horns going on over the top.”

A Full-On Freakout

Why is “Wonderwall” your favorite record in this box? Aside from”Electronic Sound,” it is the least heard and understood of your father’s Apple albums.

I remember getting a CD of it in the early Nineties and thinking, “What is this?” You’re sitting there, almost meditating to the music, literally drooling in your lap. Then a shenai [an Indian oboe] will come in and practically take the top of your head off. It’s such a deep, psychedelic record. It had Eric Clapton in it, all this backwards guitar, horns – it’s a full-on freakout record. And it was instrumental. Any singing on it was deep Hindu chants.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

It was functional music, a movie soundtrack, but also a record made for tripping – the spiritual kind.

It was a cross of spaghetti-western music, the Chants of India things my Dad with Ravi [Shankar] and the Beatles’ best freakouts. For people who haven’t heard that record, that’s the first thing you should listen to in the box. Wonderwall, for my generation, is a title associated with Oasis. It’s not. It’s one of the first things my dad did on his own, away from the Beatles.

Where did you find the instrumental outtake of the Beatles’ 1968 B-side “The Inner Light”?

My father recorded that track of his own accord in Bombay. It was part of the same reels as Wonderwall, which is why I put this version on the reissue. It sounds so different without the singing and the Beatles’ production on it.

The studio chatter at the front is fascinating – you hear George’s interaction with the players, translating his ideas into that setting.

The Indian musicians’ way of doing it is spoken – all oral. That’s the way it’s passed down. There’s a great count-in, where the Indian engineer is going “Abracadabra,” instead of “1, 2, 3, 4.” It’s a cool bit of history. For someone who hasn’t heard Wonderwall before but who knows “The Inner Light,” this gives them a better idea of where that album fits into my father’s history. That album is a missing link to the end of the Beatles.

Electronic Sounds, Extra Textures

Did you think twice about including “Electronic Sound” in the box? And I ask as someone who bought it when it came out, with the original, reversed track listing.

That took a few months to correct. The thing went to the mastering plant in England with the right titles. The plant in America reversed the labels. The Americans think that was the correct way. But it was mastered in England first. We decided to go back to the original English order.

My dad was trying to understand synthesizers. If you look at how predominant those sounds are now . . . Every synth and dance record ever made is in there. I went back and listened to it in one go. I was just laughing. If you listen to it driving at night, it’s really intense [laughs]. It’s a fun record. My dad never took himself too seriously.

Is there a narrative arc to the box – a new way through your father’s story for people who only know “All Things Must Pass”? The early Seventies were a successful time for George, but a lot of his music was overlooked. “Dark Horse” and “Extra Texture” are not spoken of with the same affection.

Those two records are bookends to All Things Must Pass and Material World, with Wonderwall and Electronic Sound on the other end. It’s like separate sets of music. I’m a big fan of Dark Horse. There are a lot of references on it for me personally, where I grew up. Extra Texture was the album I knew the least. I got to rediscover that one.

But there is a segue, from psychedelia and Wonderwall, to what he’s going to do much later in his career, like [1974’s] Shankar Family and Friends, all of the stuff he did with Ravi. Wonderwall is the first album of that, as opposed to the odd track on a Beatles record.

I think people will be surprisingly pleased with how strange some of it is, how overlooked half of these albums are. The deep tracks are among the best he ever wrote. It’s a great forest to explore.

Living in the Rare Material World

Where did the unreleased acoustic take of “Dark Horse” come from?

I’m not entirely sure. We’ve been through so many things on tapes. Getting everything together and sounding great was the most important thing. We really tried hard on this. You see stuff on the Internet: “Oh, they’re just releasing another box set.” No, no. This will be the most comprehensive release we do.

We had to do The Dark Horse Years first because of politics and legal things. It was like doing Star Wars 4, 5 and 6 first. But we had worked hard on the documentary Living in the Material World [released in 2011 and directed by Martin Scorcese]. That was a lot of archiving over seven years. We started finding all of this stuff releated to the early years. It was actually fortunate that we hadn’t done The Apple Years first.

What is in the George Harrison archives? What are the dimensions of material you’re confronted with?

It’s everything. It’s my dad’s masters – from his albums and all of the artists that recorded for his label [Dark Horse]. All of the Shankar Family projects, umpteen albums by Ravi. The Wilburys. It’s overwhelming.

How much worthy, unreleased material is in there? The CD of unreleased tracks issued with the documentary [“Early Takes, Volume 1”] was short but great.

I imagine there will be one of those at some point. But my dad was very conscious of people scraping the barrels. He hated that. I’m not obliged to anyone to put out stuff that is not up to what he would consider his standards. The scrutiny we get from fans and collectors is incredible. We release this stuff with love, and the first thing you read is, “Why haven’t you got this on there?” Well, you don’t know what it’s like to do this. It’s a thankless job. If you get it right, people go, “Wow, that’s great.” If you don’t get it beyond what people expect, they go, “You’ve buggered up George Harrison.”

I’m taking a couple of years off now. I’m going back to thenewno2, doing film scores and touring. I’m going back to the other side of my brain. If there is anything else by my dad, it won’t just be a load of scraping. It will be interesting and totally different from this set.

This is the catalog. I feel like I got it to a very good place and my dad would be very happy with it. He was always very organized. He liked to get his ducks in a row.