Holly Rankin has always felt close to nature. She feels “strange” if she doesn’t swim in the ocean every day, she says. Standing on her driveway in Forster, New South Wales, you can hear the waves lapping against the shore, no more than 100 metres beyond the end of her street.

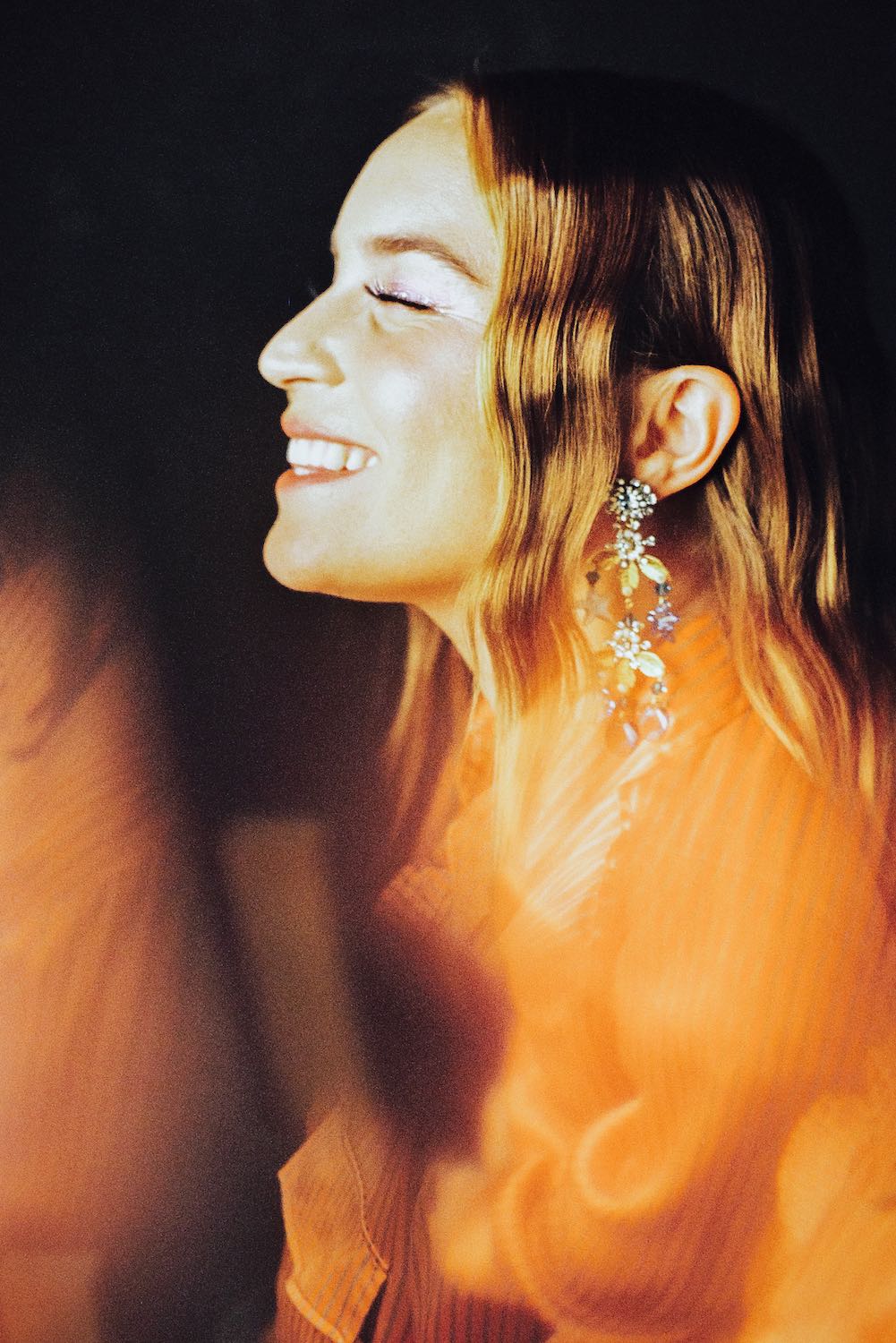

Better known by her stage name, Jack River, Holly admits she’s been swimming a little less these days. But she’s been busy.

She welcomed a daughter, Magnolia Blue (Maggie), into the world last year and recently released her sophomore album, Endless Summer. A dreamy, jangly ode to a world rapidly losing its mind (the title itself is a riff on our current climate predicament), the record feels like the best bits of the Mamas and the Papas and the Beach boys re-imagined for the Tik Tok generation (with more synth, attitude and energy to boot).

When she’s not recording or performing as Jack River, Holly has, for the last several years, been deeply involved in the climate movement. Among other projects, she worked closely with Climate200 on the Teal campaign, established a number of high-profile climate and community panels (New Energy) and festivals (Grow Your Own), publicly called out Scott Morrison and collaborated on solar projects with Cloud Control’s Heidi Leifner.

Most recently, though, Holly has been working as a Creative Director with Uluru Dialogues, where she’s been pouring her creative talents into encouraging people to vote ‘Yes’ in the Voice to Parliament referendum. With a date for the referendum now set for October 14 by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, months of hard work now approaching the pointy end.

“I just feel so alien and uncomfortable in our system, in our communities, that haven’t placed a First Nations voice at the centre of how we do things,” Holly says. “Over 80% of First Nations people want this to happen, it would make so much more sense to have something embedded….”

As part of Rolling Stone Australia’s Climate Corner series, Oliver Pelling caught up with Holly to discuss how she’s navigating the rapidly-evolving experience of life in the Anthropocene while juggling her many passions and responsibilities.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Oliver Pelling: Jack River. Holly Rankin. I want to talk to you about Endless Summer. But first, with regards to the climate, the environment, and what’s happening in Australia and around the world, how’s it all sitting with you at the moment?

Holly Rankin: We had what was meant to be a climate election in 2022 but our government is still approving coal, oil and gas projects. There’s been a hellfire summer in Europe. I’m very lucky our TV’s not working right now because otherwise I would be dying of anxiety. Personally I have moved past the point of ‘this is all going to be OK’. I’m now in the headspace of acknowledging that we’re going to a three-degree [celcius] increase world.

I’m taking five to step back from my own activism and advocacy to figure out, like, ‘what is the big thing I can do?’ How do I need to radically change what I’m doing to be of most use to the climate? Because I don’t want to play in the shallows. The [climate] situation is drastically changing, so I need to drastically change.

Climate change gets all the press, but it’s obviously downstream from behaviour – the things we’re doing and consuming. What are your thoughts on that? How can we fix the climate without fundamentally fixing how we live and consume?

We’re at this stage where, as a society or species, we need to decide whether we’re OK with letting go of ‘more is more’. With the climate and consumerism, if we just keep going, more more more more, we’re driving toward our literal demise. So can we confront less is more? Can we hold back our human egos?

I think it’s all one big magical melting pot of hopefully the demise of the patriarchy, and with that a review of consumerism, and what we’re doing here. That’s all big stuff. But I think women naturally think a little more laterally about success and what’s important. Not just because they have to, but we have a monthly cycle, we have to come back to our bodies, we go through cycles and seasons. And we need to do that now as a species.

Jack River. Credit: @xingerxanger

I know you’ve been very involved in the climate movement, but can you talk a little about your work on the Voice campaign, and why that’s been important to you?

I did a First People’s lore subject a few years ago. I learned about the Uluru Statement from the Heart and how this is the era in which we can enact something. I began having conversations with Elders where I was living like Uncle Noel Butler, he’s a Budawang Elder, and just an incredible thinker and storyteller.

I’ve been on walks with him and he’d give so many examples about if the local council had listened to him, or if the state bodies had listened to him, we wouldn’t have run into these environmental issues. He really drummed into me the power of his knowledge of the environment, and how much that could drastically impact how governments are interacting with the environment.

For me, that’s where it really clicked, and he was so passionate about the Voice to Parliament. I just realised in my advocacy and whatever I want to speak about in the future, there needs to be a First Nations voice in the room. Structurally, if this isn’t in place, it’s just going to create more dumb policy on any given topic. But especially when it comes to climate and the environment.

I just feel so alien and uncomfortable in our system, in our communities, that haven’t placed a First Nations voice at the centre of how we do things. Over 80% of people want this to happen, it would make so much more sense to have something embedded.

So I got in touch with the Uluru Dialogues, which is led by Professor Megan Davis, just to find out more about it. I got involved by trying to educate other people in music, arts and politics about it, and ended up helping with briefings before the last federal election for MPs and candidates from all political backgrounds. It was just amazing to be a part of that process.

Is there any one single message around the Voice that you really want to get across?

I know it can be hard and confusing to know how to lean in as an ally in Australia, as a non-Indigenous person. But the Uluru Statement was an invitation to Australia, and to allies, for non-Indigenous people to lean in, to support it, and to ask for it. So there’s an inherent permission in that offering to be a public supporter of it. Whether that means having a conversation with your grandmother or your next door neighbour… I really hope that allies feel more confident leaning into this, because the invitation’s there.

I read somewhere that you used to be uncomfortable with labelling yourself an activist. Can you talk about that a little? I think there are a lot of people who might currently think of themselves as ‘advocates’, but are also feeling like maybe that’s not enough anymore.

I just kind of do the work and I don’t really know how to communicate what I do. Gotta work on that. I think the term ‘advocate’ implies that you’re speaking and advocating but you’re maybe not working with your hands on the tools. And then ‘activist’ implies that you’re against the system… and I just don’t think that’s how we can think about it anymore. It’s our system, and we are entitled to be decision makers and to mold it in the way we want to.

There are just so many examples now of people changing systems and achieving progressive results without being ‘lefties’ or ‘activists’ – the Teal movement in Australia is a really great example. We are the system, and we can’t think of it as being more powerful than us anymore.

With the album, Endless Summer, I’m interested in your approach to getting the things that are important to you out there, because it’s not always literal. How do you approach making this art while you’re holding all of this other stuff?

I had to let go of trying to write literal protest songs. I wrote one, ‘We Are the Youth’, but you can’t just force your songs to be what you want them to be. So [now] I try to let the songs be themselves and use them as the emotional exhaust pipes that they are.

When it comes to the production and the story around the music, which reflects what I’m personally going through and how I’m thinking about the world, that’s where I tried to bring a bit of a take on where I’m at. So it might be a more subliminal reference to the heat-infused days. For me it kind of harks back to like, Hunter S. Thompson in the desert and the Beach Boys and these artists from the 1960s and ‘70s. They were living in a very tumultuous time politically and socially but creating escapist music.

Is there a moment on the record that you think best encapsulates that?

I really love ‘Strangers Dream’. It just paints a picture of my life, and this feeling of – both personally and as a culture – being in this stranger’s dream, including all the things we’ve talked about: patriarchy, consumerism, all this stuff. And there’s this opportunity right now to go into a different world and step out of it. It’s a story about feeling like you’re in someone else’s life, and the end of the song steps into this trippy hotel lobby where you can take the elevator down the pool and leave the dream. And there’s fun little lines in there that probably no one cares about, like ‘Shaking every hand like Scott’s in the room’ is a Scott Morrison reference.

Do you ever get anxious about sharing your work? Is that ever a barrier for you?

I don’t get anxious at all about sharing anything really – Jack River has been an incredible training ground for that. The more interesting or personal something is, the more I get excited to externalise or explore it. Through this music career, it just feels like everyone is family – that the world is your friend and you can just speak to it.

We’d be remiss not to mention Maggie. Has her arrival in your life accelerated any of your concerns or altered your priorities?

It’s like two polar ends of the spectrum. For me, like having her and thinking about her life and her world has supercharged my sense of purpose and urgency about the climate. Thinking about the future, it used to be a little bit dreamy, and now it’s very clear and concrete. Like, ‘Yep, okay, Maggie will be 50 in that year. So what will her life look like? And what can I do now to try with all my might, as a person and a mother, to change that world?’

So it’s caring about her world on one end of the spectrum, and then on the other end caring about her everyday life and trying to be a present mother for her. It’s a pretty cool journey, some kind of hero’s journey – the role of a mother in the climate crisis.

The Voice referendum will be taking place in October 2023. All Australians are required to vote in the referendum. Endless Summer, Jack River’s sophomore album, is out now on Mushroom Records. Oliver Pelling would like to acknowledge the Bunurong People as the Traditional Owners of the land on which this conversation took place. Always was, always will be.