When Saturday Night Live debuted in October 1975, New York City was in such a state of severe disrepair that the cover of the New York Post one day that month read “Ford To City: Drop Dead.” “It was just after Watergate and Saigon,” says producer Lorne Michaels. “It was a low point. A good, auspicious time to start a comedy show.”

But as Michaels learned over the next quarter-century, while the country dealt with everything from the Iran Hostage Crisis to the crack epidemic and trickle down economics, Saturday Night Live was often at its best when things were at their worst. “In bad times,” Michaels says, “people turn to the show.”

That idea was put to the ultimate test on September 29th, 2001, when Saturday Night Live had to come back on the air just 18 days after the worst terrorist attack in American history. At a time when no one was expecting to ever laugh again — when Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter had declared that “irony is dead” and comedians had been lambasted and in some cases fired for attempting to wring levity out of the cataclysm — the nation’s most popular sketch show was expected, somehow, to make people smile.

To signify that New York was recovering, Michaels asked Mayor Rudy Giuliani to make a speech at the top of the show, flanked by firefighters and police officers who had spent the past three weeks digging the remains of their colleagues and innocent civilians out of the dust; he also contacted SNL favorite Paul Simon (who also happened to be Michaels’ neighbor) to perform “The Boxer,” a paean to the city’s resiliency. Alicia Keys as the musical guest and Reese Witherspoon as host rounded out the proceedings. The end result was a show that vacillated between pathos and silliness, featuring sketches about horny mermaids and farting babies. Quality-wise, it perhaps wasn’t the strongest show SNL has done, but, if nothing else, it signaled to the millions of viewers at home that New York was, to quote from the cold open, “open for business.”

On the 20th anniversary of September 11th, we spoke with many of the the cast and crew members involved with the show, as well as a first responder who was on set that day, to learn the story of how that episode came together.

Part I: 9/11 and Returning to Rockefeller Center

It was a beautiful day. That’s what people in New York City remember the most about the morning of September 11th, 2001: It was a bright, sunny, temperate Tuesday morning, with nary a cloud in the sky. On that day, the cast and crew of Saturday Night Live was gearing up for its 27th season, which was slated to premiere on September 29th; they had already shot a handful of prerecorded material, including commercial parodies. New cast members including Amy Poehler, Seth Meyers, and Dean Edwards, as well as writers Emily Spivey and Charlie Grandy, were slated to go to 30 Rockefeller Center for the first time, running high on nerves and the euphoria of getting their big break on one of the most vaunted comedy institutions in America. Then, at 8:46 a.m., the unthinkable happened: American Airlines Flight 11, en route from Boston to Los Angeles, crashed into the north tower of the World Trade Center.

Lorne Michaels, creator and producer: I was watching television in my apartment on Central Park West and I saw the tape of the plane hitting the first tower about 10 minutes after it happened. No one quite knew whether it was an accident. Needless to say, it was on all the channels. And then the second plane hit.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Marci Klein, executive producer: I lived on West Broadway, about seven blocks up from the World Trade Center. I was at home. I heard what I thought was a bomb. I called a friend of mine who is a weatherman at NBC. I looked out my window and I saw the black hole in the building. And then it was, as you can imagine, total mayhem.

Tracy Morgan, cast member: I cried the whole week. I get choked up just thinking about it now. I couldn’t believe it. We got hit on the inside. It was like Pearl Harbor. I’m a New Yorker! Born and raised here. You couldn’t help but know someone in those buildings.

Darrell Hammond, cast member: I was asleep and my wife came in and woke me up and said, “Someone just flew a plane into the World Trade Center.” I got up and as we were watching the video of the plane, another plane collided with another building. I don’t know if this is the proper analogy, but one time I was partying in the Caribbean, and I ended up getting into trouble and waking up in a Caribbean jail and it was so hot and, God, horrific — it was something from a dreamscape. It was a nightmare. You’re not really prepared for something that bad to happen to you.

Lorne Michaels: I took my daughter, who was three, and I put her in a stroller and I walked up the west side. It was such a beautiful day. The sun was shining. It was just the right kind of temperature for a beautiful September day in that going-back-to-school way. Life there was pretty much still. If you strained your eye, you could maybe see something that was happening downtown. But people were sitting on Columbus [Avenue] in outdoor cafes. Televisions were on, but there was no general sense of alarm like we were under attack.

Seth Meyers, Jeff Richards, and Dean Edwards, during their first week at ‘Saturday Night Live’ in September 2001. (Photo: Courtesy of Dean Edwards)

Darrell Hammond: My neighbors began to talk about going outside. And then they had to come back inside because they could smell burning hair. You want to talk about a horror movie, that’s a horror movie.

Charlie Grandy, writer: It was my first season and I was wondering like, do I go into work? Will they be mad at me if I don’t go into work? So until it became clear that it was a terrorist attack, I was more worried about missing work than I was about what was actually happening.

Michael Schur, writer: Steve Higgins and I used to write these sketches for Will Ferrell where he played James Lipton — you know, from Inside the Actor’s Studio. James Lipton had asked Will to play him and then interview him, James, as him, on their, like, hundredth show or something. We were supposed to shoot it that day. I was going to the Actor’s Studio with Will Ferrell to shoot this thing. And probably the first person I talked to that day was Steve Higgins, who called me and was like, “Oh, I guess we’re not doing that today.”

Lorne Michaels: There were lots of people saying, “I don’t think you can go on.” We’ve faced that many times before, but you just have to find a way to do it. I knew it was very, very important that we show up.

At first, there were discussions among the higher-ups as to whether the show should return on its expected date, or whether the season premiere should be pushed back. The producers sought permission from Rudy Giuliani, the then-mayor who had won widespread acclaim for his steady handling of the attacks on New York City and would soon appear on Time magazine’s cover as Person of the Year.

Rudy Giuliani (as quoted in Live from New York: The Complete, Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live): I don’t remember if it was Lorne or Brad Grey who called me and actually wanted to know if I thought it was OK to go ahead with the show… I said not only did I think it was OK to go ahead with the show, I said sooner rather than later. People have to get back into learning how to laugh and cry on the same day, because they’re going to be doing [it] for a long time.

Marci Klein: Eventually when it was time to actually have conversations about hosts and stuff like that, I was not in a state of, “Let’s bring the show back.” I was just very traumatized from it, and still am.

Michael Schur: This was the message that came down from the top. It was like, this is how we contribute. You can’t suddenly become an EMT. So, unless you want to quit and enlist in the military, the way you can contribute is just by doing the show. That’s sort of the way we approached it.

Matt Piedmont, writer: I do remember walking up to work and everyone wasn’t there, it was not a full house. And it felt kind of eerie. It almost felt like when there were school meetings in elementary school at night, you go back in at night and it just felt weird. It felt like, “OK, where’s my teachers?”

Tina Fey, cast member and head writer: So many of the guys who were the regular security guys at SNL, many if not all of them were off-duty firemen who had been down there, and their weekend job was doing security for SNL. So it was very tender emotionally. People that we knew were coming right from Fresh Kills [the Staten Island landfill where human remains and personal effects were taken] to work the weekend on the show. They were saying they were doing searches for remains and then coming that same night to come to work.

Emily Spivey, writer: I went up the elevators, got off on the 17th floor, and Tina was standing there. We had met her before at the job interview. But she was standing there. The elevator door opens up and she looks at my face and she just burst into tears. And I’m like, “Oh, my God, Tina.” And she was like, “I’m sorry we made you come here.” We were all terrified. And then we hugged for like 10 minutes.

Tina Fey: It was [Emily’s] first week and Amy’s, and I’d known Amy a long time, but I do remember being like, “Dude, I’m so sorry you got your dream job and the world is going to end.”

Reese Witherspoon was the scheduled host for the season opener September 29th, and agreed to show up as planned. Just before her episode, the host for the following week, Ben Stiller, bowed out, sending the SNL scrambling to find a replacement (Seann William Scott) on short notice.

Reese Witherspoon delivers her ‘SNL’ monologue on September 29th, 2001. (Photo: Dana Edelson/NBC)

Doug Abeles, Weekend Update writer: He was in L.A. and didn’t want to come to New York, didn’t feel safe flying, which I think is very understandable, not wanting to get onto a plane at that point.

Lorne Michaels: Some people canceled who just didn’t think it was appropriate.

Tina Fey: I don’t think he was afraid. I think like so many comedians, he was like, we can’t do this without being disrespectful, or how do we do it? And he backed out. I don’t judge him or blame him for it.

Marci Klein: I didn’t want to go back to work and I completely respect any host that didn’t want to show up.

Lorne Michaels: Reese just had her baby, and she got on the plane, and she came in and she was fearless. She was great and was like, “Whatever you need.” I’ve always admired her enormously for that time.

Dean Edwards, cast member: I remember going out with Reese and her husband at the time, Ryan Phillippe. I don’t even think we talked about it. Everyone sort of had the same mentality of, hey, let’s see if we can get back to business as usual. Obviously not diminishing what we all just experienced, but doing our best to move on. Ryan Phillippe and I talked about boxing.

Hugh Fink, writer: We had the meeting with her like we always do on Monday nights with the guest host. There was a nervous energy since this was the first show back. People were very intrigued [about] what we were going to do. People were still scared. But Reese had a very calm, nice demeanor that made people think, “She’s here. She’s up for this.”

Michael Schur: It was a very British, stiff-upper-lip, “march through the rubble of World War II and open your shop” kind of mentality. It was like, “We’re not going to upend everything that we do and try to redesign the show.” The point of getting the show back on its feet was symbolically and practically saying, “The show’s still here. New York is still here. We’re just continuing on.”

Part II: “Irony Is Dead”

Immediately following the attacks of September 11th, many in the comedy world grappled with the question of whether it was even possible to be funny in the wake of such devastation. The titans of comedy at the time — Letterman, Lenos, etc. — took a measured approach, choosing somber reflection over edgy humor or the skewering of politicians. Those who deviated from that mold — like Bill Maher, whose Politically Incorrect was famously canceled after he stated that the terrorists responsible for the attacks were not cowards — were met with widespread opprobrium and cries of “too soon.” The cast and crew of SNL knew they had a responsibility to return to the airwaves and send a message to the rest of the country that life was resuming as usual, but many were haunted by the prospect of writing comedy after such a horrific act.

Tina Fey: We were just like, “What can we even remotely do? Can we make jokes about anything?”

Hugh Fink: The phrase “irony is dead” came from Graydon Carter in an essay in Vanity Fair. I love Vanity Fair, but that really depressed me. It thought, “My whole life has been sarcasm and irony. If irony is dead, then my career as a commentator is going to be dead.”

Matt Piedmont: It was such a gut-punch. I think everyone really felt like, how could you be funny? And why would you want to be at that time? Everyone knew the world changed overnight. And I remember thinking, “Oh, is this the end of fun?”

Lorne Michaels: Letterman went on [12 days] before us. I watched that and thought he did a great job. But most things [on television] were obviously somber or reporting, and we had a comedy show to do.

Harper Steele, writer: The Onion had a great front page [with headlines like “American Life Turns Into Bad Jerry Bruckheimer Movie” and “Rest of Country Temporarily Feels Deep Affection for New York] that scooped us. It was very intelligent. It was very smart. But it was such a different medium and, frankly, such an easier medium to come at it with a more critical eye than we could.

Darrell Hammond: My entire act was making fun of politicians, and we were suddenly in a place where, like it or not, and whether we understand it or not, these people that I’ve been making fun of are standing between us and another horror show. They’re the ones with the buildings burning that are coming to the door and saying, “Come this way with me.” They’re in charge of that. And people didn’t want to see them made fun of.

Matt Piedmont: At that point, even people who were far left — I remember at the time going, like, “Oh, shit, Bush actually did a pretty good job of at least getting behind the desk and talking to America.” So I think there wasn’t really a take that Will [Ferrell, who played Bush] could’ve done at that particular time… I don’t think we wanted to bring down our leaders at that point.

Michael Schur: I remember thinking, “It’s not possible to continue to do this job right now as every second of your day, from morning to night, is filled with the sound of ambulances and fire trucks. And the smoke is not only visible from the southern tip of the island, but is at times, depending on the wind, wafting over you.” I was like, “We shouldn’t do this. It’s crazy.” And then we just kind of did it.

Part III: Writing the Episode

After it was established that the show would return, the writers and cast members were faced with a Herculean task: How do we acknowledge that the world has changed forever, while not bumming the audience out? They reached a consensus early on to avoid topical humor and rely instead on lighter fare, such as fan favorites like Celebrity Jeopardy (which was added on the Friday before the show), a sketch in which Reese Witherspoon played a horny mermaid, and a sketch about a baby who couldn’t stop farting.

Dean Edwards: I remember [head writers] Tina and Dennis [McNicholas] saying they were going to keep things as evergreen as possible.

Tina Fey: It was very, very raw. Not even the darkest comedian was going to go right at it on TV.

Charlie Grandy: The dress rehearsal for that first episode, in one of the jokes we just showed a picture of Osama bin Laden and it chilled the audience. I mean, it just was — you couldn’t go anywhere near it.

Darrell Hammond: The people who were off limits for a while were Bush and Giuliani and Cheney.

Michael Schur: It wasn’t like we were kowtowing to the corridors of power. It was just that first week, [making fun of Bush or Cheney] wasn’t what people were going to enjoy, and it just wasn’t going to work. It wasn’t going to work comedically, it wasn’t going to work culturally.

Hugh Fink: One thing that was so weird to me at the time was there was a decision by the creatives at SNL — I didn’t get to weigh in on this, but — we were not go use the words “terrorism” or “terrorist” on the show. I thought that was Kafka-esque. To me, it was sort of, “How can we ignore what just happened?

Lorne Michaels: I don’t recall this. But I’ve been hearing things like this my entire career. “Someone from the network…” And you go, “Who?” There is always something that is told to me, but [the network] leaves me alone…. We’re not that show.

Emily Spivey: I do remember pitching early on — who sings “Proud to be an American”? [Lee Greenwood; the song is called “God Bless the USA.”] That was a song that would come on, like, every 45 seconds, and I pitched that the singer-songwriter’s wife was praying that he would write a different song. I remember that got a little bit of a laugh. And then I tried to write it with Will Ferrell and it ate it at the table. That was the level of political humor at that point.

Left to right: Will Ferrell, Dean Edwards, Reese Witherspoon, and Darrell Hammond in “Celebrity Jeopardy” on September 29th, 2001. (Photo: Dana Edelson/NBC)

Hugh Fink: I remember having spirited arguments with fellow writers on the show. My position was: We’re the show that’s supposed be risky and to make people uncomfortable with comedy. We should not back down on this show. This is a great opportunity to remind people why SNL is so important. It’s not just funny, but it’s relevant. We’re going to do stuff here that not everyone is going to like, and it may disturb you, but in the same way that Dave Chapelle or another contemporary voice might say some things that are upsetting or challenging, that was my hope for what that show is going to be.

Harper Steele: I wrote a sketch in the first episode that was about a farting baby, which is not beloved by anyone.

Emily Spivey: I got a sketch on with Maya [Rudolph], which was her Donatella Versace impression. Which was a big deal for someone’s first show, to get a sketch on — I’m not bragging or anything, it just, like, never happens. It was between that and another sketch — I think it was with Dean Edwards and maybe Horatio [Sanz] — that took place on a stoop in New York, and it was like two guys talking about an antiterrorism plan, an antiterrorism backpack, like, “Here’s what you’re going to do.” They were both up for grabs. So Maya was in costume. Dean was in costume. And then we hear over the intercom, “Emily Spivey to the booth.” I had to run down to the booth, like while Alicia Keys was performing. I can’t remember [why the antiterrorism sketch was cut] — if they were like, “Oh we don’t want to talk about, we don’t want to go there.”

Hugh Fink: I wrote a sketch about Cat Stevens, who was going by Yusuf Islam then. My sketch was a commercial for Yusuf Islam’s newest album. It was Will Ferrell as Cat Stevens. Will is a genius and a great singer. I basically took all of Cat Stevens’ classic songs and changed the lyrics to make them about 9/11. He had the song “Peace Train.” I changed it to “The F Train.” It was about people seeing someone that looks Arab on the New York subway and their reaction to it. It did really well at the table read and it got picked. We did it at dress at 8 p.m. that night. I think the crowd was somewhat uncomfortable. That’s because if you look at the show that aired, it was so soft. My sketch really [would have stuck] out like a sore thumb. It was directly commenting on what had happened. And it was cut.

Lorne Michaels: I don’t remember this exactly, but I do know that I had Cat Stevens, when he was working as Cat Stevens, on the show I was doing in Canada in the early Seventies. I spent a week with him. I didn’t think it was worth going after anyone that night.

Robert Smigel, writer: I attempted some topical-ish sketches with celebrities trying to say something meaningful and failing, like [Chris] Kattan’s Antonio Banderas talk show… It ended up pushed to the second show. I even tried one where Will crashes the monologue, wanting to help the host get laughs by doing a broad, dumb character in purple diapers and suspenders. When it bombs, he reassures everyone “Folks, it’s OK to laugh. Just let it out, you won’t believe how good it feels.” Will actually did the best, funniest take on well-meaning buffoonery in that second show, as the guy who comes to work in “Patriotic Shorts.” I think that’s probably the sketch everyone remembers and loves, because it was so silly but somehow relatable. We were all feeling devastated, helpless, and wanting to do something to make a difference, but not knowing exactly what. That’s pretty much how we approached that first show. So, even though it would’ve been nice for it to have had a piece like “Patriotic Shorts,” there’s no judging the choices made, because there’s no right answer. Everyone was entitled to react and respond to this impossible tragedy in their own way.

Witherspoon’s monologue — which the show’s writers say is always the hardest segment of SNL to write any week — was particularly dicey. She ended up telling a lengthy joke about a baby polar bear who isn’t sure if he’s actually a polar bear, because, as the punchline goes, “I’m freezing my balls off.”

Emily Spivey: I remember discussions about, “What the heck is the monologue going to be?” And that’s always a discussion, let alone after 9/11, when you don’t really know what at what level can we be funny.

Hugh Fink: Word came down that we were not going to address 9/11 in her monologue. I think not only did she not acknowledge any specifics about it, but she told an old joke. It was something that was sort of a disconnect.

Lorne Michaels: The joke about the polar bear was given to me by Randy Newman, and I laughed. I thought, “Maybe we can do that.”

Hugh Fink: If she had done that joke any other show, any other season, as a viewer you’d go, “Oh, Reese Witherspoon. She’s likable. She’s not a comedian. We give her slack since she’s a pretty, talented actress telling a joke.” But at the time, it seemed like a bit of a disconnect. Not only was she not addressing 9/11, but, we’re going in the opposite direction. We’re not saying terrorism. We’re having a host that’s telling an old joke about a polar bear.

Part IV: The Cold Open

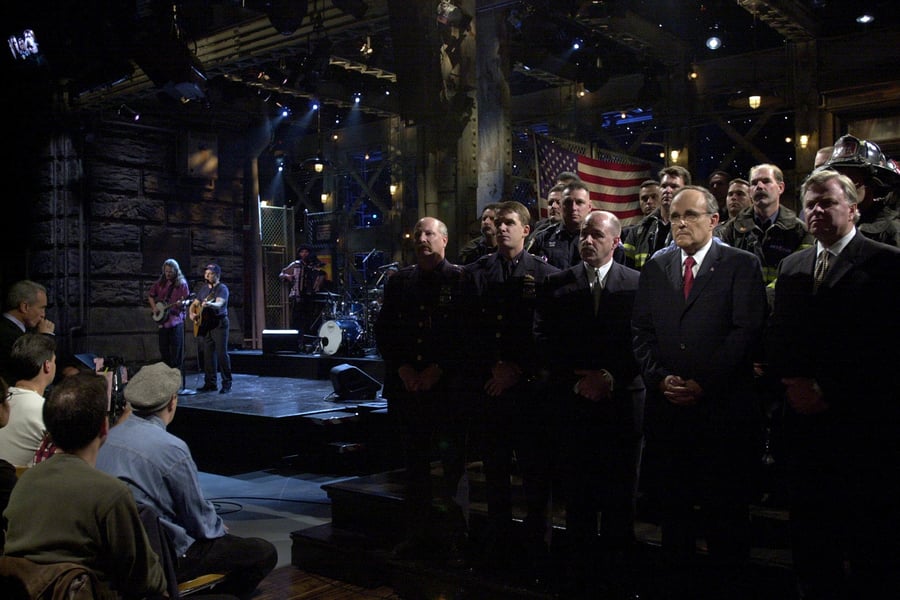

By far the most memorable segment of that night was the cold open, in which Mayor Rudy Giuliani gave a short speech flanked by then-NYPD commissioner Bernard Kerik and then-FDNY commissioner Thomas Von Essen, as well as first responders. “Good evening. Since September 11th, many people have called New York City a city of heroes. Well, these are the heroes,” Giuliani began, referring to the grim-faced firefighters and police officers behind him, many of whom were still reporting to the Twin Towers site daily to try to dig up remains. Michaels’ longtime friend Paul Simon also performed in the cold open.

Tina Fey: It was Lorne’s idea to have all that — to have Paul Simon specifically doing “The Boxer.”

Lorne Michaels: I kept thinking, “You can’t do entertainment. We can’t open upbeat. But we also can’t do a dirge.” And Paul Simon doesn’t have much choice in my life since he lives next door. In the end, I thought, “The Boxer” kind of summed up New York. The character in it doesn’t quit. “The fighter still remains.” Anyway, I thought I could use that.

Paul Simon (from a 2006 Iconoclasts interview): If my memory is correct, I think he just said, “I think you should sing ‘The Boxer.’” I said, “Is that the one you think is right?” Lorne said, “I think that somehow makes a statement about persevering and enduring.” I, of course, said, “Whatever you want of me, I’ll be happy to do.”

Michael Schur: Everyone was like, “Oh, [he’ll do] ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water.’ There you go. Boom, done. Like, maybe Art Garfunkel will come and they’ll do a duet or whatever.” Then we heard it was “The Boxer,” and I remember thinking, “That’s the wrong song. What are you thinking? Like, it’s a Bob Dylan narrative song about a guy who leaves home and becomes a boxer. What are you talking about?” Then he sang it. And I listened to it for the billionth time, but heard it for the first time, and was like, “Oh, this is exactly the right song.” It’s about perseverance and strength and about fighting. And I was like, this is exactly what this city needs right now, is the goddamn “Boxer.”

Lorne Michaels: And then I knew the mayor. We weren’t close friends, but I knew him because he had been around the show. I called him and I said that we were going to come on, and I wanted him to come. He brought the fire chief and the police chief.

Members of the FDNY, NYPD, and Port Authority Police, with (front, left to right, in ties) Police Commissioner Bernard Kerik, Mayor Rudolph Guiliani, and Fire Commissioner Thomas Von Essen during the ‘SNL’ 9/11 tribute. (Photo: Dana Edelson/NBC)

Francis McCarton, former deputy commissioner of public information at the NYC Office of Emergency Management: We were working 20-hour days at that point. I probably went home once during that entire time period.

Michael Schur: Giuliani was the story that week, 100 percent. He was this thing that we all latched onto at the time that made people feel like somehow or another we were going to figure this out and get through it, like Cuomo [with the Covid-19 pandemic]. Which, by the way, makes it so sad what happened to him — like, whatever series of of brain-eating bacteria infiltrated his skull 10 years ago and have slowly driven him into his current non-human vegetative state.

Lorne Michaels: There has never been a political figure, in my opinion, who fell from such a high level. He was inspiring. He was honest, tireless, and he did a lot of good. And then, of course, when you do that, someone says, “You should run for president.” You go, “No, no. He shouldn’t.”

Harper Steele: I do remember giant firemen in big outfits walking around. They were eight feet tall and 300 pounds.

Francis McCarton: There wasn’t a lot of laughter. There were a lot of funerals. There was a lot of, you know, notifications and bodies. And then you start talking about body parts — it’s just mind-boggling. So we didn’t have a lot of time to laugh.

Lorne Michaels: On the day of the show, a whole group of first responders who had been down at Ground Zero for that whole time came to the studio. This was the first time out. When they walked into the studio, it was that thousand-yard stare. They looked at us. We looked at them. They were still covered in the dust. That was stunning.

Emily Spivey: I remember coming down the stairs to check cue cards and seeing all the firemen coming in to go to studio 8H. I stepped out of the way to say, “After you,” and then burst into tears. Everything was just so emotional.

Tracy Morgan: I can remember patting a fireman on the back. I saw this smoke, this dust, come off his jacket from 9/11, and I broke down crying, right on stage, man. It was heavy. I get choked up now just talking about it. It was a part of my life I’ll never forget.

Marci Klein: The thing I remember the most was the smell of them when I met all of them. The same thing my apartment smelled like — the smell of September 11th [on] their uniforms.

Michael Schur: In my opinion, the best joke told the entire seven years I was there is the joke [Lorne] wrote, which is, “But can we be funny?” And Giuliani saying, “Why start now?” It’s self-referential in a way that SNL has always been, and it was so smart that he gave the punchline to Giuliani, because everyone loved Giuliani so much in that moment.

Lorne Michaels: In Canada, I was part of a team on television and I did the straight lines. I knew how to do that. […] I knew it would work. At dress, Rudy — because he’s not a professional comedian, that came later [laughs] — he did what nonprofessionals do: He started to smile, because he knew he was coming to a really funny line. I said, “Rudy, you cannot smile. You are tipping a joke. It has to be done completely straight.” We rehearsed it, and he’s good on air. But if you look closely at me, and I haven’t in 20 years, I think I’m scowling at him, like “Do not smile.” He said some words about New York, and then I had my line, and he had his. He got the laugh. And then we were at “Live from New York” and we were starting again.

Tina Fey: Just to get permission to laugh from that guy — if you can remember a time when that guy was viewed very differently — just to get permission to do the rest of the show, was very smart.

Darrell Hammond: I do remember the size of that laugh, and I know that room when everyone in the room laughs at the same time. It’s quite a sound.

Hugh Fink: I was so pissed off about that cold open. Lorne never asked my opinion, not that he cared what I thought. I just thought what we did could have been on any TV show airing that night. It had nothing to do with Saturday Night Live. You’re doing this emotional, heartfelt version of “The Boxer.” You’ve got Paul Simon singing it sincerely. The lighting is deliberately not upbeat. It’s very introspective and mournful. When the camera panned to those cops and firefighters standing stoically onstage in uniform and then, of course, panning over to Guilani, I remember going, “Wow, this is not the message I was expecting Saturday Night Live to be sending. This is flag-waving. This is very patriotic. But there’s absolutely no edge, and it’s not funny. It’s just dead serious.” It’s how I feel about Super Bowl halftime shows or the preamble to the Super Bowl. It’s like, “They’re going to bring out the flag! They’re going to bring out kids from a Christian group!” They’ll just throw every possible symbol that represents knee-jerk, rah-rah America. I felt that’s what the cold open did.

Harper Steele: I think this is where people look back in time and think there’s something maybe mawkish or uncritical or not very ballsy about that opening. And so my response to that would be, there’s just no way to go back in time and give people a feeling of what the world was like at that moment. It’s almost indefensible at this point, but I defend it by saying that it was a different world.

Dean Edwards: Things just kind of froze for that one moment when Don Pardo announced, “Ladies and gentlemen,” and the credits ran. There was electricity. That’s the best way to describe it. There was electricity in the air.

Part V: Weekend Update

One of the toughest segments to write that week was Weekend Update, the long-running news parody that was then being hosted by Jimmy Fallon and Tina Fey. Because Update was inherently topical, the writing team, which was newly led by future Parks and Recreation and Good Place creator Michael Schur, struggled with how to properly imbue the dismal news cycle with levity.

Michael Schur: The poor writers that week, their first week back, have nothing but the scariest possible shit. I mean, just the worst, most awful, horrifying stuff, in the middle of the city where it happened.

Doug Abeles: I came across a story about a restaurant in North Carolina called Osama’s Place, and it was under pressure to change its name for obvious reasons. I can pull up the joke for you: “A man who owns a Middle Eastern restaurant named Osama’s Place says he won’t change the restaurant’s name because it’s named for the original owner and not Osama bin Laden. Though he had a harder time explaining why his other restaurant is named Hitler’s Chicken.” That’s I think as close as we could come to addressing 9/11 on Weekend Update.

Lorne Michaels: I can’t remember what we did on Update. I don’t remember much past my line, frankly. But we were just trying to find things that would play — that were clearly comedy, but would play with the audience. Our job was to sort of brighten the atmosphere.

Tina Fey: I remember Lorne saying to me and Jimmy, “No one wants to see your existential crisis.” He didn’t want us to get emotional.

Charlie Grandy: That morning, the real question was, what’s the first thing we say out of the gate? How do we acknowledge what’s happened? Jimmy and Tina were wondering, “Can we come and say, ‘Hey, I’m Jimmy Fallon. I’m Tina Fey.’” And then what do you say? How can you encapsulate everything — your sadness, your fear, welcoming people back? And again, it was just the simplest thing. They ended up saying “And we’re glad to be back.”

Courtesy of Dean Edwards

Michael Schur: The setup [for the first Update joke], as I remember it, was: “The CIA was looking for bin Laden in a dark place where not a lot of people were. So they were checking theaters that were showing Glitter.“

Alex Baze, writer: I figured it had to be a stupid joke, it couldn’t be a capital-I “important” joke. Because the only thing you could do is burst the bubble of tension that had to be in that room.

Michael Schur: I don’t think I’ve ever experienced a more cathartic laugh in my life than the live show when that joke was read. I can recall that feeling in my body right now: just like a wave of relief, you know, like, the feeling where something bad almost happens and then it doesn’t. You almost get into a fender bender or you almost send the wrong text to the wrong person by accident. And then you catch yourself before you do it and you’re like, “Oh God, oh God, oh, thank God I didn’t do that.” That’s the feeling that I had always had about that moment.

Alex Baze: It was one of my proudest moments, because just for me personally, as a joke writer, that was the first time I did a really good job in my own head of assessing the room.

Tina Fey: We led with a Glitter joke? Yeah, I guess that was the best we could come up with [laughs], but I don’t remember the joke.

Robert Smigel: Tina and I wrote a piece for Update where Joan Rivers [played by Ana Gasteyer] waxes about how trivial everything is in light of what’s happening. As she self-flagellates, she still somehow slips in gratuitous jokes about Barbra Streisand’s nose and hawks QVC jewelry. That one was also reworked for the second show, as an Emmys red-carpet sketch.

In the most overtly political (and dated) segment of Update, Darrell Hammond appeared to give a monologue in blackface as Jesse Jackson *69-ing with the Taliban, referring to the telephone code that would dial back the most recent number that had called you.

Michael Schur: The greatest thing that can happen is if someone not directly related to what’s going on decides to insert him- or herself into the narrative, just like, “I’m not a part of it, but I’m going to jump in front of a camera and I’m going to become a part of this.” And Jesse Jackson had, I believe, made some kind of statement about being available for wartime negotiations or hostage negotiations. And it was like, “Thank God, because now we don’t have to go after Bush.”

Darrell Hammond: I remember most of the words: “I did not contact the Taliban. They, in fact, contacted me. What happened was this: I had a hang-up on my machine, so I did star-6-9.”

Michael Schur: Leaving aside the bad optics of a white actor playing an African American person — which 20 years ago was a lot more kosher, I would say, than it is now. Even though at the time we were also like, “Is this OK? I dunno. Oh well.” And then we just did it.

Dean Edwards: [The blackface] is a whole other conversation. I understand why people are offended, were offended. I think, for me, if I had done an impression of Jesse Jackson at the time, I would have been pissed because, like, I’m Black, so why not let me do it? But I did not do an impression of Jesse Jackson at the time.

Darrell Hammond: I specifically remember that we were going through different shades. And we were ready to pull the plug at any time. I mean, I don’t ever want these guys to hate what I’m doing. [But] I heard through one of the band members who is close with the family that [Jackson] absolutely enjoyed it.

Tina Fey: We had some information at the end of Update of like, here’s where you can donate, and Lorne basically was saying, “Don’t cry when you do this. Nobody wants to see that.” He was wisely wary of anything feeling performative emotionally.

Dean Edwards: If you watch the end credits, everyone was just cheering that we’d survived it…. It was like the end of Return of the Jedi where the Ewoks and all of the characters from Star Wars are clapping and, you know, Luke is with Obi-Wan Kenobi and Anakin Skywalker is with Yoda, chilling. I was hearing that music. That’s how it felt.

Part VII: After the Show

The afterparty, a weekly cast tradition, was the first chance that first responders and Giuliani had to blow off steam since the Twin Towers had fallen 18 days earlier.

Emily Spivey: At the afterparty, we were all talking to the firemen and the policemen. This is a famous story, but Rachel Dratch was really hitting it off with this one fireman. We were all like, “Oh, my God, she’s going to hook up with a fireman. This is so fantastic.” And then he turned out to be gay, the fireman. And so that was a joke for years, with Rachel Dratch going, like, “Leave it to me to to pick the gay fireman.” And so then that later became a sketch called “The Girl with No Gaydar.”

Lorne Michaels: We went to a party afterwards and the mayor was there, the fire chief, and everyone just drank. I think it was the first time that Rudy had any time. I think he left the party at 4 or 5 a.m. He had to go to a memorial service at a church for a fireman who had been killed. His assistant Manny [Papir] told me the next day that he was just sitting there in the pew, white as a ghost, and probably still a little drunk. The priest came out and said, “Mr. Mayor, follow me.” And he took him into a little room with a bed and said, “Lie down.” I think everyone was running on adrenaline at such a level that he wouldn’t have known.

Emily Spivey: I remember walking home with with Dratch and Maya. And just out of the blue, and this is the kind of thing that would happen in the city right after that time, there are these four guys dressed in Revolutionary War garb coming down the street playing instruments. One was playing a fife. Just sort of somberly walking down the street. And as they walked down the street, everyone stopped and just sort of listened and watched them as they went by, holding an American flag. It was just so surreal and so beautiful in a weird way.

For the remainder of the season, the writers slowly tried to regain their footing, going back to toppling totems of power and criticizing foreign policy, particularly after the U.S. invaded Afghanistan. It was a struggle, at least at first.

Darrell Hammond: They say that tragedy plus time equals comedy. 9/11 won’t ever be funny, but it became, over time, possible to make fun of politicians again.

Hugh Fink: It felt different, at least for several shows after 9/11. These topics kept coming up. Jokes for Weekend Update. Jokes about Islam and jokes about Arab Americans. How far can we push it? Is this offensive? I do think it had a big impact on that whole season.

Tina Fey: I remember arguing about certain cold opens early on. Somebody wrote a cold open about liberals overcompensating and blaming themselves, and I was just like, this is not the take. Like, “9/11 happened last week and we’re going to use it to beat up Upper West Side liberals? This is not the take.” I remember being sort of real pissed about it.

Darrell Hammond: You’ll notice, for months, we went light on the politicians, light.

Harper Steele: I wrote a sketch that was very critical of the Afghan War [“War Party,” in which smug partygoers break out into song over invading Kandahar]. I just watched it for the first time in 30 years or something, and I didn’t think it was that great, but it immediately came up on Twitter with people trolling SNL for being in the pocket of the industrial military complex, just crazy stuff. And then smarter people started to defend it for its satire. And, you know, the Internet doesn’t understand satire.

Emily Spivey: There’s that famous sketch where Will Ferrell came in — I think Matt Piedmont wrote it, actually — where Will is wearing the britches that were the American flag [during the October 6th Seann William Scott show]. That was the level of [political] humor we were at. And I think that was a pretty safe, decent, fun level to be [at].

Matt Piedmont: Literally the Sunday after [the Reese show], I remember my wife and I were walking downtown on Broadway. Fourteenth Street was closed off, so downtown there’s no traffic. I don’t know if you remember, but you’re getting sold ridiculous flags. It was Super-Patriotism-Ville. It’s like 20 bucks for “Love America,” “USA.” We’re walking and I’m going, goddamn, there’s so many fucking flags. And I literally go, “Oh, that’s so funny. You can’t call someone a jerk if they’re being a patriot, because now they’ve got carte blanche, or diplomatic immunity.” So I wrote that sketch in my head right away. Amy Poehler said afterwards, that was the first sketch where she felt like she could laugh again. That was the first time I think it seemed like it might go back to normal.

An anthrax scare at 30 Rockefeller Plaza in early October reignited the atmosphere of panic and fear at SNL.

The Rockefeller Plaza news ticker flashes a headline about a case of anthrax poisoning at NBC on October 11th, 2001. (Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Lorne Michaels: The anthrax happened the week that Drew Barrymore hosted.

Tina Fey: I remember sitting in my dressing room on the ninth floor going through the Update joke packet, and I was watching the news, and I saw Lester Holt come on [with] breaking news, saying there was anthrax in 30 Rockefeller Plaza on 15, and we’re on 30. Probably anybody who wasn’t an adult at that time, it might be hard to remember how deeply paranoid and afraid everybody was. Every day would be like: “Yup, is it today? Is it anthrax? Is it today?” And it was like, yup, it’s your day. I just had a panic attack, basically, and picked up my things and left, and passed the host’s dressing room, where Drew Barrymore was. And I thought, “Should I tell Drew?” And I’m like, “No, man, I’m out.”

Lorne Michaels: For me, because I’ve just been doing it way too long, I went, “The anthrax is on the third floor. We’re on the eighth floor. When you go into the elevator, don’t press three.” It was sealed off. I didn’t think we were in danger, but it was scary. It was a very serious thing. I know the facts. It was very serious. We didn’t know that then. Everything that was happening was on the news, and we were in the building with the news.

Tina Fey: Lorne eventually called me later that night and was like, “We’re all here. Do you want to come back? We could get dinner.” So I think I was the only person that freaked out and left.

Marci Klein: It was not easy to go back in the building for me. I was scared of terrorists. I was scared to be back in the building. To this day I can’t be on high floors -— I like the idea that I can get out fast of a building.

Dean Edwards: Tensions were running high, to say the least. It was a very, very tense time to be there.

Part VIII: SNL‘s Post-9/11 Legacy

The years that followed 9/11 were a tumultuous time marked by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Bush’s re-election campaign, Hurricane Katrina, and the financial collapse of 2008. The SNL creative team did their best to keep the show current while maintaining its comedic edge.

Tina Fey: I remember shows like The Daily Show being such a big deal with Jon Stewart that it put more pressure on [our] show to have more politics and have a clear point of view in politics.

Charlie Grandy: I think [the 9/11 episode] showed what SNL could do, but also the limitations. And I do feel at that time, like post-9/11 and then with the Bush administration, people wanted a harder take.

Emily Spivey: The Daily Show and all those kinds of shows sort of usurped SNL in a way. Suddenly, SNL wasn’t seen as the place to go to for political comedy necessarily.

Alex Baze: Certainly everyone’s political and social awareness spiked after 9/11. I don’t want to be gross, but as a society, we’re probably looking inward more than we would have. There’s the spike in activism that came out of the wars, the resulting wars, that has changed comedy in a lot of ways.

Matt Piedmont: Things are so fragmented now. There’s not one platform that people tune into that everyone’s collectively watching. So I think that [SNL] took that responsibility seriously, of being one of the last places where a lot of people of a lot of ages tune in and wanted to have some comfort.

Emily Spivey: It mirrors what’s going on now a little bit — just the wet bedspread of fear that’s covering all of us every minute, every second of the day now. It’s really destabilizing. You want to look at your favorite things, your favorite shows, you listen to your favorite music to find that comfort. And I think SNL being such a New York show, it was really helpful for everyone to see that show up and running. Because then it was like, “OK, we’re going to be OK. We’re taking baby steps to start to feel normal again.” Even during Covid, when you saw SNL coming back and doing “SNL at home,” because they did those Zoom shows. There’s like a stabilizing effect to it. Like, “We can still do the show live. And things are going to be OK.”

Tracy Morgan: Everyone has their Vietnam. When 9/11 came, I knew what my father went through in Vietnam. The trauma stays with you for life. It doesn’t go anywhere. You have to learn how to manage it. And after 9/11, we had to learn how to laugh again. We had to build a bigger tower. This is America, motherfucker! We had to build a bigger one!

Francis McCarton: You’re dealing with, every single day, pulling bodies out of a pit. The loss of life of first responders at the time was one you couldn’t fathom. So to be able to laugh again, and have a good laugh with the people you’d been with every day — you know, laughter is healing.

Michael Schur: People remember that show in the way that you remember like the first time your friend made you laugh after your father passed away or something like that. The whole world got disrupted in a violent and horrifying way. And I think that for some percentage of them, the thing that brought a step back towards normalcy was SNL.

In honor of the 20th anniversary of 9/11, Rolling Stone is looking back at how the terrorist attacks changed America at the time — and for the next two decades.

From Rolling Stone US