As on-the-road misbehavior went, it was pretty tame. On tour in Seattle in the spring of 1972, Jeff Forehan and three of his shaggy-haired bandmates got ahold of some weed. Squeezing into a hotel bathroom, the pop singers happily toked up, using the ceiling fan to suck up the smoke and ensure they weren’t caught.

Except they were — by some of their other bandmates, no less. The next thing they knew, Forehan and his fellow performers in the band — the Young Americans — were having what he calls “a little confrontation” with the head of the group. Alerted to their secret stash, he told them they had to go straight to their rooms after each night’s show; one singer who objected was soon kicked off the tour. “I say this with all due respect, but some of the other kids in the group were cut from a different cloth, a bit more squeaky-clean,” Forehan recalls. “What we did pissed off a lot of them.”

Rock & roll may have dominated the Sixties, but not every teenager or early twentysomething back then was taken with electric guitars, cryptic Dylan lyrics or Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Some were happy to sing pre-rock standards like “Swanee” or songs from Oklahoma! while dancing in lavishly choreographed numbers and wearing matching sweaters. This style – let’s call it choircore – offered a bizarro alternative to sex, drugs and rock & roll, replacing it with chasteness, soda pop and show tunes, along with the occasional Simon and Garfunkel, Leonard Cohen or soul cover. With choircore, adults were able to pretend that the rock & roll revolution wasn’t really happening — or, at least, to maybe ensure that some of the youth of the Sixties didn’t fall prey to it by offering up another, more virtuous option. And for a time, it worked; choircore groups toured the country, popped up regularly on variety shows, recorded for major labels, scored the occasional hit single and — way before Kid Rock and Ted Nugent — were invited to the White House for PR-stunt purposes.

The choircore brigade included the Mike Curb Congregation, led by the songwriter, producer and future Republican lieutenant governor of California. Dubbed in one article of the time as “a dozen or so of the most wholesome-looking young folks you’ve seen this side of Disneyland,” the Congregation sang cheery, lusty, hardy-voiced versions of Robbie Robertson’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” and the Beatles’ “Come Together” — like Lawrence Welk after he’d stumbled upon FM radio. Their harmonies swarmed around Sammy Davis Jr. on his Seventies hit “The Candy Man.”

Up With People, a multi-voiced choir from Tucson, would burst into buoyant folk pop numbers like “What Color Is God’s Skin” and their “Up with People” theme song (“If more people were for people/All people everywhere/There’d be a lot less people to worry about”) along with “The Star-Spangled Banner.” As one of its members said at the time, “I’m fed up with the image of American youth being created by beatniks, draft-card burners, campus rioters and protest marchers.” Johnny Mann, who sang backup on early rock & roll records by Eddie Cochran, formed the Johnny Mann Singers, who turned the Yardbirds’ “Heart Full of Soul” and other rock-era tunes into barbershop pop and starred in their own syndicated variety show, Stand Up and Cheer!

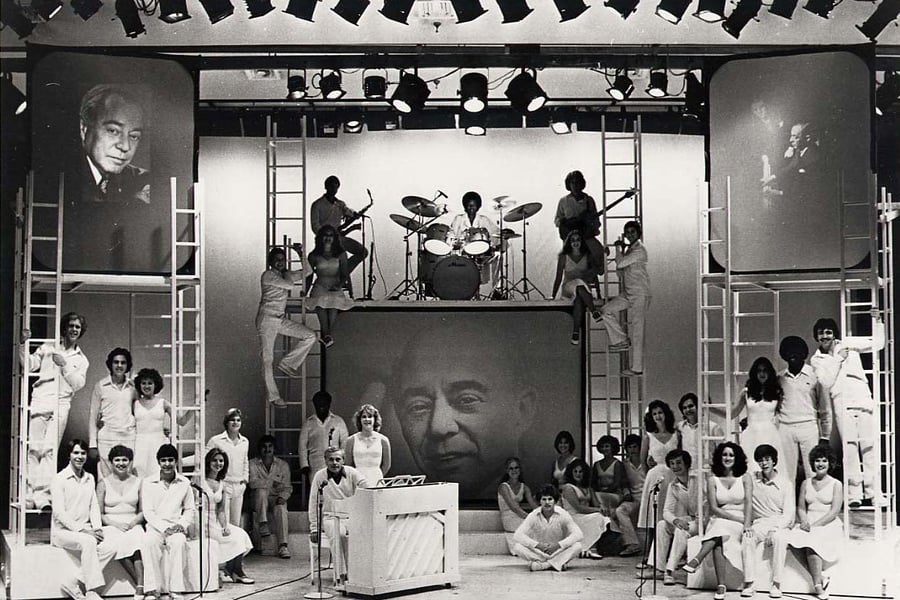

Amid this short-lived wave, the Young Americans were among the most celebrated of choircore groups. They invented the concept of a show choir, setting the stage for the song-and-dance ensembles seen in Glee and the Pitch Perfect movies, and were parodied on Saturday Night Live. A movie about them took home the Oscar for best documentary. Their alumni include everyone from singer-actress Vicki Lawrence, best known for her role on The Carol Burnett Show and Mama’s Family, to, most surprisingly, Carolyn Dennis, a respected singer and actress who went on to sing backup in Bob Dylan’s Christian band in the late Seventies (and then marry and have a child with him). As Dennis recalls, “The Young Americans were the foundation of everything I did after that.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Yet starting with the time some of the bandmates started smoking weed, the Young Americans’ story wasn’t so one-dimensional. Unlike its choircore peers, they spoke out against the Vietnam War and were sometimes politically progressive. And whether the group knew it or not, the U.S. government may have tried to use them as a propaganda tool. “It was meant to be young, intelligent kids reaching out and spreading the love through beautiful music,” says Lawrence. “But we got wrapped up in all the showbiz stuff.”

Milton Anderson had a dream — make that two. Born and raised in Illinois, Anderson, who had the look and demeanor of a hard-bitten, high-forehead elf, earned a degree in choral music in Cincinnati and, by the early 1960s, had moved to Los Angeles, where he wound up as a musical director for CBS TV shows. After then becoming a high school music teacher in the San Fernando Valley, he caught a glimpse of the future. “He saw kids standing on the choir rises dying to move, and he thought, ‘What if we put them on their feet and did simple choreography?’ ” recalls Randy Neece, who joined the Young Americans in 1966.

Enter the second dream. Anderson, who was in his early thirties, also grew frustrated that the well-behaved, fresh-faced students filing into his classrooms were not being represented in the media. “The newspapers and magazines always dwelled on the young troublemakers and hippies,” he said in a 1963 interview. “Every day I saw hundreds of lovely young people entering my classes, and I decided it was time to do something to set the public straight.” Adds Neece, “He didn’t have a problem with the counterculture. He had a problem with the other side not being represented at all.”

Auditioning students from local high schools and colleges, Anderson picked the best few dozen and dubbed them the Young Americans. Funding came easily: Thanks to his TV connections, one of his principal financial benefactors was Rod Serling, host and creator of The Twilight Zone. The rules for membership were simple: You had to be between the ages of 15 and 21 (after which you were booted out), had to maintain good grades and had to be able to sing, dance and read sheet music, with more emphasis on show tunes than anything on the radio at the time.

Anderson’s timing couldn’t have been better. In 1962, the year the Young Americans were launched, the Beatles had yet to arrive in America, and the charts were dominated by middlebrow pop as rock & roll recharged after the death of Buddy Holly and the disappearances, for various reasons, of Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard and other wild men from the previous decade. The Young Americans, with Anderson largely offstage but popping up as an occasional conductor, made their TV debut on a Bing Crosby special in November 1963, just weeks before John F. Kennedy was killed.

In the aftermath of the president’s assassination, the country was in the mood for something jolly and upbeat, and the sight of 36 cherubic young men and women performing “A Salute to the Roaring Twenties” did the trick for lots of viewers. Before long, the Young Americans were on the road with pop crooner Johnny Mathis, who hired them as an opening act and had his company, Rojon Productions, work with them. “They were everybody’s idea of good, wholesome American youth,” Mathis recalls. “They were a group of young people who were doing exactly what everybody would love to see young people do.”

In 1965, the Young Americans released their first album, The Young Americans Presented by Johnny Mathis, which included their chorale versions of the girl-group hit “One Fine Day” and “Chim Chim Cheree” from Mary Poppins. “Even though rock & roll was on the radio, we always felt we had a feather in our cap that we were giving another side of music,” says Mathis. “We were very aware of that.” At a time when half the country was freaking out over the rise of rock & roll freaks, groups like the Young Americans reassured American adults that not every kid was in fact a would-be stoner with shoulder-length hair and a closet full of Stones albums.

Few if any of the members of the Young Americans seemed to object. “I didn’t like the Beatles,” says Larry Lloyd, a California high school student in the group at the time. “I don’t remember anybody being gaga over them. I liked their songs, but I didn’t like the way they performed them. I was never a rock & roller, and I don’t know many in the group who were.”

The group did, however, have its counterpart to Dylan’s 1967 British tour doc Don’t Look Back: A full-length feature film, that same year’s Young Americans, followed the group on the road, albeit with markedly more clean-cut hijinks, like boat rides, a trip to a carnival, and impromptu song performances at tourist sites. The raciest the movie got was a scene in which Lawrence, who had joined the group while still a high school student in 1965, discovers that her hotel room comes with a vibrating bed. “Jesus, I don’t remember that,” she says. “Oh, my God. But I don’t remember there being a script. It was, ‘Here’s what we’re doing in this scene.’ Almost like a loosely scripted documentary.”

Anderson’s rules and regulations were as much a part of the movie as the performances. Group members were not allowed to engage in PDA, and in one scene, two of them, who would later marry, talk over that rule with Anderson. In another hotel-room scene, boys in the group put on wigs (and, in one case, a dress) and pretend to be a “wacky” rock & roll band, to the screaming delight of the others. Coming upon the commotion, an irked Anderson tells one Young American he’ll have to apologize to each and every guest in their hotel, and the kid agrees.

The Young Americans did scant box-office business, and The New York Times panned the 104-minute movie, calling it “a sort of middle-aged, wish-think movie” and stating “for anyone interested in America’s fantasy life, the movie is an absolute must.” At the Oscars in 1969, it walked away with the statue for Best Documentary, but the glee was short-lived: When the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences learned that the film had been screened at least once before the eligibility period, actor and AMPAS head Gregory Peck personally called director Robert Cohn to tell him he had to return the statue. It’s still the only time in Oscar history that such a reversal has ever occurred. To add insult to injury, the award was given to Journey Into Self, a doc about a 16-hour group therapy session.

But for a moment, the Young Americans ruled in their particular universe. “Three of us did promotion for the movie and went to the premieres, and we were treated like rock stars,” recalls Lloyd. “This lady invited us to her house for barbecue, and after, I went back to our hotel and called my parents and said, ‘We went to the house of this cool lady, Joan Crawford — ever heard of her?’ She and Betty Grable — those were the kind of people we were around. It was cool.”

For Anderson, it wasn’t enough just to present and maintain a freshly showered and shaved image for his choir. He also wanted to make the Young Americans a sort of musical Peace Corps. As he announced in a 1963 interview, he hoped to enlist either private donors or the State Department to promote a Young Americans tour of Europe. “We were led to believe,” Dennis recalls, “that we were young ambassadors of goodwill in the world.” In preparation for those trips, the choir would study foreign languages. “It was taking the position that there were solid citizens in America, and not everyone was at Kent State throwing bottles,” says Jim Morey, a Young Americans road manager who took on management duties in 1968. “Generally speaking, we wanted to show that young people in the United States were good kids.”

Whether the Young Americans ever received government backing remains foggy. The State Department could not locate any documentation on the Young Americans, and Morey says no government-sponsored tours of Europe or Asia happened under his watch. But the late Don Riber, an executive at Mathis’ Rojon company, boasted in a self-penned article in 1975 that the State Department “helped arrange and send them on a world tour,” most likely in the years between 1964 and 1967.

Asked about it now, Mathis says the group was never officially sanctioned by the U.S. government. But he doesn’t deny any connections, either. “We were all for any kind of assistance we could get, so to have the people who were involved in government or any kind of legitimacy, that’s what we were looking for — and a lot of people wanted to jump on board and a lot of people did,” he says. “Especially when we started to travel to Asia and different parts of the world. It was fine to be sanctioned by any kind of governmental assistance. They were very proud of anybody who traveled to others countries and that were known as good, wholesome American youth.” Mathis, however, says there was no financial assistance for any such trips.

Some of the Young Americans’ competition were happy to align themselves with the rising right. The Mike Curb Congregation sang the theme song for Richard Nixon’s 1972 campaign and later Ronald Reagan’s, and Curb himself dropped “pro-drug” groups like the Velvet Underground from MGM Records when he took over the label in 1969. Yet despite his group’s conservative-sounding name, Anderson never wanted the Young Americans affiliated with a particular political party or philosophy. On tour, he would rotate roommates so that white and African-American members would be able to get to know each other.

But in light of their name and image, it was perhaps inevitable that the Young Americans would be dragged into politics. With the help of the U.S. ambassador, plans were drawn up to show the Young Americans movie at the Moscow Film Festival in 1967 — until the Russian government rejected it, deeming the movie “unacceptable,” most likely as propaganda. “No commissar could accept this view of the United States or its youngsters as truth,” the Los Angeles Times agreed at the time.

For the Fourth of July in 1970, the Young Americans participated in an “Honor America Day,” with Johnny Cash and Republican-leaning acts like Bob Hope and the Rev. Billy Graham. Even stranger was a ceremony at the White House in July 1971, after Congress passed the 26th Amendment, lowering the voting age from 21 to 18. To make clear the impact the new law would have, Nixon invited three 18-year-olds to stand beside him during the signing, introducing them as members of the “Young Americans in Concert” singing group. In prepared remarks, Nixon acknowledged their upcoming overseas tour: “I have been thinking about what kind of message you would be taking to Europe, what you would be saying. You are going to be saying it, of course, in song, but you will also be saying it by your presence, by how you represent America.”

There was only one problem: the “Young Americans in Concert” were not the actual Young Americans but a knockoff group. It wasn’t the first time it happened, either. The group’s original choreographer left the organization and launched the Doodletown Pipers, who mimicked the Young Americans’ hale-and-hearty look and repertoire. Another time, according to Lloyd, some Young Americans left to form a spinoff when they learned that some band members had been canned. (Another enticement was financial: Disneyland, where the offshoot often performed, paid, but Anderson didn’t; the company was non-profit, although the kids did receive on-the-road per diems.) The departures and spinoff groups still hurt, though. “They took the same look and style and choreography,” says Neece. “That really hurt the Young Americans.”

The arrival of weed into the Young Americans’ world was just one of many moments when the real world intruded on the group’s carefully groomed ecosphere. “Here we were in this cocoon, and everyone was happy as if the world was a perfect place,” says Dennis, “but then the real world would hit you in the face.”

Dennis, a 15-year-old high school student in Watts in 1969, had first heard about the Young Americans thanks to her high school music teacher. “I was told all this weird stuff: ‘You have to go live with these people and you can’t go out alone and they always make you sure you travel in pairs,’ ” she recalls. “It made me a little frightened.” Her mother, an experienced singer and songwriter herself, assured her daughter that the Young Americans had “a great reputation” and encouraged her to audition. Dennis was soon a member. Having grown up with R&B, gospel and musicals, she was only marginally familiar with rockers like the Beatles herself: “Wasn’t there a movie called Yellow Submarine? I remember thinking, ‘OK, but where’s Doris Day?’ ”

Although its members were largely white, some, like Dennis, were African-American, and in the early days of the band (before Dennis), the occasional protest broke out when the group pulled into a Southern town. A hotel in Mobile, Alabama, refused rooms to the African-American Young Americans, leading the entire group to walk out; to protest segregation, one member drank out of a “blacks only” water fountain and was almost arrested. Some concertgoers were unnerved by the sight of black and white group members dancing together during a tribute to the Charleston, the Twenties dance craze. “That was a shock to us all,” says Neece. “We had never experienced anything like that. It wasn’t all bubblegum and sweetness. There were some dicey moments.”

One recurring aspect of their concerts, especially at high schools, were postshow “rap sessions” — talking, not rhyming — with students. Group members weren’t prohibited from expressing their opinions but were told to do so respectfully. As Forehan recalls, “I remember them saying to all of us, ‘On these interviews, be careful not to use any foul language. You can say your views but be pleasant, be nice, and have manners.’ ” At one such session after a show in Illinois in 1972, Forehan and two other Young Americans openly expressed their disdain for the then-raging Vietnam War, and school officials abruptly terminated the interview. As fellow Young American Rick Conyers (who has since died) told the local newspaper after the incident, “Some people don’t think of us as individuals. They think we’re all Republican and all from the same block.”

As the Sixties gave way to the Seventies, the Young Americans also had to cope with an increasingly rock-oriented landscape. Their 1969 album, Time for Livin’, included not only the extremely chipper title song but also two Simon and Garfunkel covers (“For Emily, Wherever I May Find Her” and “Scarborough Fair”). Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne” and Otis Redding’s “Hard to Handle” entered their repertoire, and they persuaded Anderson to let them sing songs from Jesus Christ Superstar. But getting the rest of the world to go along with their modernization was trickier. Time for Livin’ would be the only Young Americans album to make the charts — peaking at a lowly number 178.

With its choral versions of the Beatles’ “Here, There & Everywhere” and the Blood, Sweat & Tears-associated “You Made Me So Very Happy,” the group’s 1971 album, Love, took the upgrade a step further. But the album — complete with a cover that showed guys in green V-neck sweaters and white pants and women in one-piece yellow dresses, still a very straight image for the time — didn’t chart at all, dooming the group’s recorded career. “It’s the age-old thing: If you want to get played on the radio, you have to perform what the radio’s going to play and keep somewhat contemporary,” says Morey. “It was hard to sound contemporary on Top 40 radio with a 36-voice choir.”

By the late Seventies and into the Eighties, the Young Americans were struggling to fit in with the times. On a 1977 episode of Saturday Night Live with guest host Ray Charles, cast members Gilda Radner, Bill Murray, John Belushi, Jane Curtin, Laraine Newman and Dan Aykroyd donned sweaters and became Charles’ white-bread backup group, “The Young Caucasians.” Variety shows were in decline, affecting the group’s profile. “There was no Ed Sullivan, Dean Martin or Andy Williams anymore,” says Bill Brawley, a former member who is now the group’s artistic director. “So what do you do?”

The Young Americans scoured the world for other arenas, like American military bases in Asia. Into the Eighties, on tour in the Far East, they tried to be relevant, with sets that included covers of songs by Donna Summer and Barbra Streisand (“Enough Is Enough”) and Linda Ronstadt (her faux-new wave hit “How Do I Make You”). When Las Vegas began its short-lived reboot as a family-fun destination, Anderson, who’d long been wary of bringing his troupe there, relented.

It would prove to be a mixed blessing. The Young Americans were perfectly at home in Vegas, where they would often open for Liberace. The lavish, in-the-closet entertainer became very taken with group singer Cary James, and the two eventually became partners. “I wasn’t aware of [the Liberace affair] — not that I could have done anything about it,” says Morey. “We became aware that there were kids in the group who had their own sexual orientation.”

For Anderson, who was open-minded but strove to maintain the group’s controversy-free image, it was “a very difficult time,” says Neece. The affair returned to haunt them in the HBO film Behind the Candelabra. Based on the book by Liberace’s lover Scott Thorson (played by Matt Damon to Michael Douglas’ Liberace), the movie re-enacts the Liberace-James relationship. But in retrospect, few are shocked that the affair happened at all. “It wasn’t a big surprise,” says Lloyd. “But what are you going to do? You’re in the entertainment industry, for God’s sake.”

More than five decades after the choircore scene arrived, some of its proponents have survived. Up With People still exists as a Glee-style touring company, and the Mike Curb Congregation released a gospel tribute to Billy Graham in 2011; others, like the Doodletown Pipers, are only recalled by the most ardent choircore historians. In 2002, Anderson reconceived the Young Americans as a musical education and outreach program as well as a touring act. The organization has since opened its own school: The Young Americans College of the Performing Arts, in Corona, California, just east of Anaheim, offers performance degrees in voice, dance and “general understanding of cultural regions of the world.” In 2017, it was officially accredited, around the same time that Anderson, at 90, died of complications from a stroke. In what was an almost perfectly poetic finale, he died near his Michigan home on July 4, 2017, after watching a parade featuring local kids who’d been trained by the current Young Americans.

The list of former Young Americans includes Fame and Walker, Texas Ranger singer-actress Nia Peeples, country singer Skip Ewing, Broadway director Jerry Mitchell (Kinky Boots) and Lawrence (currently on the Fox sitcom The Cool Kids). Forehan went on to work in the stage crews of Prince (during the Lovesexy tour) and Bananarama, and Dennis starred in the Broadway production of The Color Purple and sang backup not only for Dylan but also for Bruce Springsteen as part of his 1992-1993 interim, non-E Street ensemble.

The current Young Americans roster includes 350 active members; at any given time, five casts are on the road, from the States to Japan and Germany. Taking a break from rehearsals in South Dakota, Young Americans creative director Brawley runs through the current group’s repertoire. The American show opens with Macklemore and Ryan Lewis’ “Can’t Hold Us” and includes a tribute to jukebox musicals featuring songs by Carole King and ABBA. “We’re listening to whatever is happening,” he says. “The Greatest Showman — the kids all know those songs.”

For former members, the legacy of the group lives on in other ways. Few involved can forget the fast-paced shows, the pressure to make sure the right outfit was placed by the side of the stage for the next, super-quick costume change. “When I tell people about it now, they can’t believe it — ‘Oh my God, you were a Young American?’ ” says Forehan, who currently teaches rock history, recording techniques, and commercial music production in California. “But losing my costume or forgetting my lines — I still have dreams about that, man.”

[Editor’s Note: A version of this story was originally published in April 2019]

From Rolling Stone US