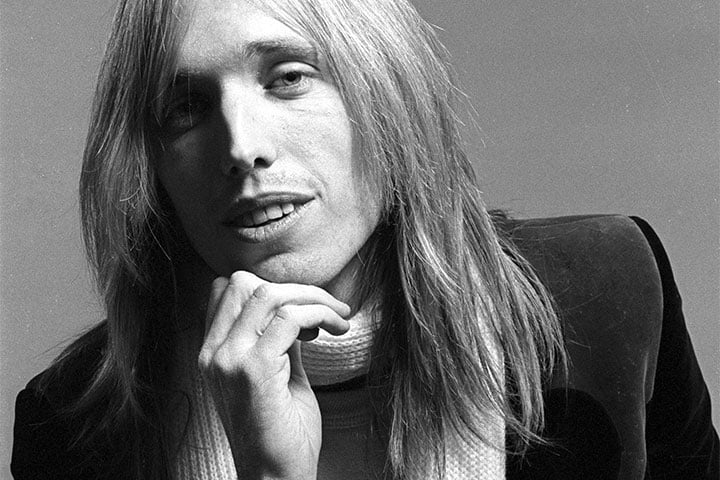

On September 25th, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers performed the final concert of a three-night run at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles. It was also the climax of their 40th Anniversary Tour, a 53-show celebration of the singer-guitarist’s unbroken lifetime with his band as one of rock & roll’s biggest, best and most committed live acts.

Thirty minutes before he walked onstage, Petty welcomed singer-songwriter Lucinda Williams into his dressing room. “He had a big smile, and he was putting a cough drop in his mouth,” says Williams, an old friend who had just finished her opening set. “I didn’t want to stay too long. It was getting close to showtime. I said, ‘Tom, the audience is rockin’. They’re good to go. I’ve warmed them up for you.’ He looked at me and goes, ‘I bet you did,’ with those twinkly eyes and that beautiful face.” They hugged; a photo was taken. It was, she says, “the last time I saw him.”

Six days later, on the evening of October 1st, Petty suffered cardiac arrest at his home in Malibu, and was rushed to UCLA Medical Center in Santa Monica. He died at 8:40 p.m. the next night, after a daylong vigil by his family, friends and bandmates. Petty was less than three weeks from his 67th birthday.

“I got the phone call and told the folks in my house,” Bruce Springsteen says, recalling the sudden, shocking impact of that news. “There were shrieks of horror. You couldn’t quite believe it. We were from the same generation of rock & rollers. We started around the same time and had a lot of the same influences. And when I lived in California, I got to know him quite well. He was just a lovely guy who loved rock & roll and came up the hard way.”

On that last night at the Bowl, in his adopted hometown, the Florida-born Petty covered every mile of his journey with determined, jubilant force: his creative odyssey as a songwriter; the commercial success that continually followed him; the record-business trials that came along with it; his eternal garage-band bond with the Heartbreakers — lead guitarist Mike Campbell, keyboard player Benmont Tench, bassist Ron Blair, multi-instrumentalist Scott Thurston and drummer Steve Ferrone. “We’re just gonna throw a bunch of records up in the air and see where they fall tonight,” Petty told the sold-out crowd in his sandy, slow-as-molasses drawl, early in a two-hour streak of legacy that was, in fact, decisively chosen and largely set in stone throughout the tour.

There was the early signature jangle of “American Girl” from the 1976 studio debut, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, and the legendary perfectionism of “Refugee” — more than 100 takes in the studio, Petty claimed — from his 1979 multiplatinum breakout, Damn the Torpedoes. Much of the show was given to generous spins through the intricate balladry and pointed reflection on Petty’s acclaimed solo outings, 1989’s Full Moon Fever and 1994’s Wildflowers, with profound glow and muscle from the Heartbreakers. And Petty highlighted strong recent work like the heavy-blues rave-up “I Should Have Known It,” from 2010’s Mojo. “He got the balance he wanted,” Campbell says of the 40th Anniversary shows, “and the story he wanted to tell.”

Very few people beyond the Heartbreakers’ immediate circle knew that Petty was suffering, at each gig, from a hairline fracture in his left hip, which he planned to deal with after the tour. “I don’t know how it happened,” says his longtime manager Tony Dimitriades. “I don’t think he even knew when it happened.” At one point, Dimitriades told Petty, “You can’t tour like that.” The singer responded, “Why not? I’ll do it in a chair if I have to.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Petty postponed two shows in late August due to laryngitis. He was otherwise in vintage road-warrior form, according to J. Geils Band singer Peter Wolf, who saw the real deal when Petty and the Heartbreakers opened shows for the Geils Band in 1977. This summer, Wolf and his solo group did the honors for Petty. “He was going through some great pain” from his hip, yet “put on long, stellar shows,” Wolf says. “I’d watch him coming down from the stage. There was an inner force driving him.”

“He was just kicking ass,” Tench says of Petty, “and we had found another level of playing as a band. There was a depth of soul coming through.” The two men spoke briefly after the September 25th show at the Bowl, raving about it. “I figured I’d get a call in a month or two: ‘Tom wants to get together and jam some shit out.’ ”

“It was magical, it was spiritual,” Campbell affirms. “Everybody was so happy, especially Tom — full of glory and hope.” The guitarist was particularly pleased when Petty threw “Breakdown” — a nugget from the first album, only played twice before on the tour — into the closing-night set with striking high harmonies by backing vocalists Charley and Hattie Webb.

“I’m just so sad,” Campbell says now, “to think that I’m not going to play those songs again.”

“I haven’t seen this outpouring since my dad passed,” says Dhani Harrison, a few days after Petty’s death. Dhani — the son of Petty’s close friend, the late Beatle George Harrison — notes that when his father died in 2001, “someone said, ‘I’ve never seen so many grown men cry.’ The same thing can be applied to this.”

“I was never afraid to pick up the phone and explain a situation to him,” says Stevie Nicks. “He would just talk me down.”

Tributes swiftly followed the news of Petty’s passing. On October 3rd, Springsteen dedicated the first preview performance of his solo Broadway residency to Petty. Wilco, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Coldplay, Fleet Foxes and the War on Drugs were among the bands that covered Petty’s songs onstage. U2 played bits of “Free Fall-in’ ” and “Learning to Fly” during “Beautiful Day.”

“I thought the world of Tom,” said Bob Dylan, who hired Petty and the Heartbreakers as his road band in 1986, then became Petty’s bandmate — with Harrison, early rock & roll legend Roy Orbison, and Jeff Lynne of Electric Light Orchestra — in a supergroup, the Traveling Wilburys. “He was a great performer, full of the light, a friend,” Dylan said of Petty, “and I’ll never forget him.”

In a dramatic acknowledgment of the grieving across America that week for Petty and the victims of the October 1st massacre at a music festival in Las Vegas, country singer Jason Aldean — who was onstage there when the shooting began — opened the October 7th episode of Saturday Night Live with “I Won’t Back Down,” Petty’s anthem of iron will and moral certainty.

“That put me off when I wrote it,” Petty said of the song in a 2009 Rolling Stone interview, one of many conversations I had with him over the past decade for the magazine and his SiriusXM channel, Tom Petty Radio. “It’s so bare, without any ambiguity. There was nothing there but truth.” But, he admitted, “that was my mindset: I will survive. I will move on.”

“Tom never settled for anything but the best, on any level,” says Campbell, Petty’s musical partner since 1970, when he joined the singer’s early Florida band, Mudcrutch. “That was one of the great things about him. He didn’t settle for just being OK.”

The Heartbreakers, 1977: Blair, Campbell, Petty, Tench and Lynch (from left).

Petty entered the last year of his life with confidence and pride. In December 2016, during a radio interview to announce the 40th Anniversary Tour, he described a recent rehearsal with the Heartbreakers, their first in two years. “We had the amps up loud,” Petty told me with a delighted chuckle. They also broke out the blues and covers: “Smokestack Lightning,” “Kansas City,” Fleetwood Mac’s “Black Magic Woman.” “The band sounds amazing,” Petty exulted. “It just locked right up.”

Then, on February 10th, 2017, Petty was honored by MusiCares, the musicians health-care charity, as their Person of the Year at a dinner and tribute show. By the time Petty and the Heartbreakers closed with their own set, a broad corps of stars and disciples including Williams, Foo Fighters, Don Henley, Regina Spektor, the Bangles and the modern-rock band Cage the Elephant performed Petty songs from across his entire canon.

Randy Newman opened the evening, playing “Refugee” alone at a piano. “His hooks, his titles — when he gets to them, it’s solid as a rock,” Newman says, likening Petty “in a remote, odd way” to the legendary pop songwriter Burt Bacharach, “who winds all over the place. But when he gets to the hook, slam, it’s there. Petty didn’t wander. But those hooks and titles are so memorable.”

Stevie Nicks reprised her duet with Petty, “Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around,” a Top Five hit in 1981. The Fleetwood Mac singer attributes his uncanny ability to write for and about women — the scrappy fighters in that song and 1978’s “Listen to Her Heart”; the restless dreamer in “American Girl”; the romantic ideal in “Wildflowers” — to “the really strong women” around Petty: his first wife, Jane; their two daughters, Adria and AnnaKim; and his second wife, Dana, whom he married in 2001.

“Tom was a completely masculine personality,” Nicks says, “but it softened him and made him much more understanding.” Nicks, who first met Petty in 1978, “was never afraid to pick up the phone and explain a situation to him. And he would just talk me down.”

At MusiCares, Cage the Elephant delivered a potent unplugged twist on Petty’s 1993 hit “Mary Jane’s Last Dance,” a deceptively jaunty folk-blues about holding on to a fleeting passion. Cage singer Matt Shultz contends that like David Bowie, Petty “conquered the popular belief that creativity dies with age,” especially in rock & roll. “The more experience he had, the more it enhanced his ability. He became stronger.”

“No one could understand the pace I’m running at,” Petty said in our radio interview. “My family’s complaining that I don’t take any time off.” Earlier this year, Petty produced an album, Bidin’ My Time, for an idol: Chris Hillman, the singer-bassist in the Byrds and a founding member of the Flying Burrito Brothers. And Petty was keen to work on the next album by his protégés the Shelters. “It was a short walk, 20 steps, from his front door to his studio,” Dimitriades says. “He’d be there every day.”

During a meeting with his label, Petty cleaned his nails with a switchblade. “I wouldn’t have hurt anybody,” he said.

One of the projects that had been put on hold when Petty died was an expanded reissue of Wildflowers — all of the tracks for the intended double album plus additional, unreleased songs — followed by a tour showcasing Petty’s breakthrough writing on that record. “That would have been smaller-scale, away from the hits,” Campbell says. But “plans for that somehow evolved into ‘It’s the 40th year. Let’s do this tour first.’ ”

In a 2014 conversation with Rolling Stone, Petty recalled the unique genesis of Wildflowers, pointing to a day when his co-producer, Rick Rubin, played him the Beatles’ demos for their 1968 double LP, The Beatles. “It hit me how strong the songs were,” Petty said, “with just a couple of acoustic guitars. I would try to write in the same fashion. I started to hear a whole new kind of thing coming out.”

Petty was flattered when Hillman asked if he could record his own version of Wildflowers‘ title track for Bidin’ My Time. “It is a song of pure love — agape,” Hillman says, using the ancient Greek word. “Then you look at it now. It’s almost prophecy: ‘You belong in that home by and by.’ Most of Tom’s stuff — you could describe it as minimalist. But less is more.”

Petty returned to the Wildflowers project before his 40th Anniversary marathon was over. “He asked me to call some people,” Dimitriades says, “and see if they would come on the road and perform it with him. One — and she said yes immediately — was Norah Jones.”

“It’s so hard to believe it’s even happened,” Dhani Harrison says of Petty’s death. He remembers, as a child, a Christmas in L.A. with the Petty and Harrison families — Dhani and Adria playing Nintendo with their rock-god dads. And there was the day that an advance copy of Full Moon Fever arrived at Friar Park, the Harrisons’ English estate. George put it on his jukebox, Dhani says, “and just had it on repeat.”

Earlier this year, Dhani stopped by Petty’s house to play him some new music: Dhani’s first solo album, IN///PARALLEL. “He put the record on in his studio, put his head in his hands and listened to the whole thing from start to finish,” Dhani recalls. At the end, “he looked at me, gave me this big, beaming smile, and said, ‘Guess you found your target demographic.’

“He was so proud, like a dad,” Dhani says. “I’m sure thinking about that in the future will make me lose it. What could be cooler in the entire world than for your target demographic to be Tom Petty?”

With Dana, his second wife, in 2007.

Petty characterised his roots and ambition this way, in the title song of his 1985 album, Southern Accents: “I got my own way of talkin’/But everything gets done, with a Southern accent.” He was born Thomas Earl Petty on October 20th, 1950, in Gainesville, Florida; a brother, Bruce, arrived in 1958. Their mother, Kitty, “was a very kind, good person,” Tom said in 2009. Their father, Earl, was “Jerry Lee Lewis if he didn’t play the piano. He was scary and violent. He beat the living hell out of me.”

In 1961, an uncle working on the local set of an Elvis Presley movie, Follow That Dream, arranged for Petty and some family members to watch the filming and meet the star. “He’d met my aunt before,” Petty recalled. “She said, ‘Elvis, this is my nephew and my niece.’ He said, ‘Hi, how are you?’ Then he went to his trailer.” In that moment, Petty claimed, Presley “made my life.” Aside from a few odd jobs in his youth — in a Gainesville musical-instrument store, as a groundskeeper at the University of Florida, short stints in a barbecue restaurant and a funeral home — Petty only played, wrote and recorded music for a living, until his death.

Another epiphany came in 1965 when Petty — then a member of a local combo called the Sundowners — went to Jacksonville for his first concert, headlined by the Beach Boys and featuring two British Invasion bands, the Zombies and the Searchers, who became crucial influences on Petty’s lashing-jangle charge and pocket-grenade songwriting with the Heartbreakers. Petty later discovered that Campbell, who grew up in Jacksonville, also went to that show.

The two finally met in Gainesville, where Campbell was supposed to go to college but instead ended up playing with Petty in Mudcrutch. “We connected instantly, like we’d known each other already,” the guitarist says. There was also “this thing that set us apart from the other musicians in town — this drive to write our own songs.”

By 1974, the future core of the Heartbreakers — Petty, Campbell and Tench, another Gainesville native — had played on Mudcrutch’s debut single, “Depot Street.” Released the next year, it was a commercial bust on Shelter Records that eventually broke up that group. Petty later got a solo deal with Shelter but turned to Campbell and Tench again to form a band — with Petty’s name up front, playing his songs. “Mike and Benmont are good, smart people,” Petty said in 2014. “They were cool with it right away.” Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers — with Blair and original drummer Stan Lynch, both from Gainesville — released their self-titled debut album in November 1976, then hit the road in earnest.

“The influences were obvious — the Byrds, a lot of the Merseybeat stuff,” Wolf says of Petty and the Heartbreakers’ 1977 sets opening for the J. Geils Band. “But Tom would close the show by doing ‘Shout.’ It’s a challenging song to do, once you’ve heard the Isley Brothers’ version. I was always amazed how they did it their own way. And every night, they got multiple encores.”

With Damn the Torpedoes, Petty and the Heartbreakers became that rare phenomenon in rock: a critically acclaimed band that packed arenas, sold albums in platinum numbers — including the 1985 experimental concept, Southern Accents — and made challenging singles that were popular on Top 40 radio, FM rock stations and MTV (the eerie menace of “You Got Lucky”; the electro-psychedelic haze of “Don’t Come Around Here No More”). “Tom was a great classicist,” Springsteen says, “and the Heartbreakers were a real guitar band. The music was beautifully written, beautifully constructed. But Tom’s attitude and personality gave it a modern edge.”

Tench believes that as a writer, Petty “walked in this strange penumbra between the shadow and the light.” “Free Fallin’,” Petty’s Top 10 single from Full Moon Fever, “has a catchy chorus,” Tench says. “But there is a story and sorrow that is brilliantly laid out.”

During the Heartbreakers’ stint backing Bob Dylan in 1986 and ’87. “I thought the world of Tom,” Dylan said. “He was full of the light.”

Petty’s dark side — manifested at times in an explosive temper; more often channeled into a willingness to wage all-out war with the music business over his integrity and just reward — was a running parallel drama to his success. He famously fractured his left hand when he punched a wall during a contentious mixing session for Southern Accents. Petty declared bankruptcy while making Damn the Torpedoes to force his way to a more equitable record deal.

“I certainly don’t have a chip on my shoulder,” he told me in 2014. “I was just trying to do the best job I could.” Still, Petty confirmed with relish a story about a meeting to renegotiate a contract during which he pulled a switchblade knife out of his boot and started cleaning his fingernails. “I was just that kind of guy,” he said. “And those meetings are really boring.” But, he insisted, “I wouldn’t have hurt anybody.”

Mounting tensions within the Heartbreakers over Petty’s creative grip culminated in Lynch’s departure in 1994. Bass guitarist Howie Epstein, who joined in 1982 when Blair decided to quit the road, was let go in 2002 over his addiction to heroin. (Blair returned; Epstein died of an overdose in 2003.) Petty fell into his own hard-drug use in the Nineties as he coped with a difficult divorce and a rough spell — musically, commercially, emotionally — with the Heartbreakers. “It wasn’t the best period in my life,” Petty confessed in 2006. “But I am through it. I came out the good side.”

Nicks credits Campbell with being a vital, balancing force in Petty’s life. “Michael is such a gentle soul,” she says. “Michael and Tom were able to get through anything because they were the yin and yang of it.” Petty was “in some ways not the easiest person to get along with. Michael was able to be the calming factor.”

Petty, in turn, took the unique nature and benefits of his leadership seriously. “It really wasn’t Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers — it was Tom Petty in the Heartbreakers,” claims Ferrone, an English-born session musician and former member of the Average White Band who played drums on Wildflowers as a sideman prior to becoming a Heartbreaker. Before an encore on Ferrone’s first tour with Petty in 1995, the singer asked him if he knew “Breakdown.” The drummer said no; it wasn’t on the list of songs he was supposed to learn.

Ferrone recalls Petty’s response: “Tom says, ‘OK, this is what you do. You play this beat [Ferrone mimics the song’s distinctive shuffle]. The crowd will go crazy. Follow me.’ That was the rehearsal. And here’s the thing: He didn’t have an ego. It wasn’t ‘You don’t know my most famous song?’ That never came into it.”

Petty “was so smart,” Campbell says, as well as “one of the funniest people I’ve ever known. And he had a good heart.” The guitarist recalls a point “several tours ago” when he was having “some real personal problems. I was doing my job but struggling to keep my vibe up.” One night, in the middle of a song, Petty came over to Campbell, “stood next to me, and he goes, ‘Just remember, up here, nobody can touch us.’ ”

In Del Mar, California, September 17th. His last show came eight days later. “Everybody was so happy,” Campbell says. “Especially Tom.”

Springsteen calls it “the debt” — the chance, if it comes, to honor a pivotal teacher and repay that gift of inspiration. “You know that without this guy and without that guy, there would be no you.”

Petty spent much of his stardom in ready, grateful service to his rock & roll elders. In addition to backing Dylan on the road and making two albums with the Traveling Wilburys, Petty produced a 1981 comeback album for the early-Sixties rock & roll singer Del Shannon, Drop Down and Get Me; backed Johnny Cash, with the Heartbreakers, on the country titan’s 1996 album, Unchained; and appeared as a singer and co-writer on a 1991 album by the Byrds’ Roger McGuinn. Petty also found the time to relaunch Mudcrutch — with original guitarist Tom Leadon and drummer Randall Marsh — for two studio albums and national touring, the kind of action they never enjoyed the first time around.

That work produced lasting friendships, especially with Dylan and George Harrison. “I never sought these people out,” Petty claimed when I asked him in 2009 about why he got along so well with legends. “Every one of them came to me. Obviously, they liked something we did. At times, I think they were looking for some help, like, ‘I need to put a band together.’ We had this unit. Bob used to say, ‘These guys communicate without talking.’ He liked that.”

Petty “had a great bullshit detector — he didn’t suffer fools, just like my dad,” says Dhani Harrison. While Petty and George Harrison “were kind of stone-y, mellow dudes, they had that toughness. They’d kick your ass. But they loved the same stuff — ukuleles, motor racing. They would go to the Formula One races together.”

George “really felt at ease with Tom,” Dhani says, “because it was like having another you next to you. There were more eyes watching out for you.”

Dhani recounts a story that Petty once told him about the Heartbreakers’ tour with Dylan — a story that “says everything about the way Tom interacted with people: honest but cheeky.” Onstage one night, Dylan kept complaining that the stage lights were too bright and threatened to leave if they were not turned down. Finally, Dylan walked off, forcing Petty to coax him back on as the Heartbreakers kept playing.

In the wings, Dhani says, “Bob was going, ‘Fucking lights. I’m not going back out there. It’s like fucking Disneyland out there.’ And Tom says to Bob, ‘You’ve never been to Disneyland.’ Bob just started laughing. Tom called him on it, straight out. They walked back out there and carried on playing.”

With Petty’s death, three of the five Wilburys are gone (Orbison died in 1988), and the Heartbreakers have lost their voice and leader. But, Tench says, “I never want this guy to be thought of as ‘OK, we’ve put him in the file, that’s done.’ Because he resonates. There’s a reason why he was in the Wilburys with Bob, Roy and a Beatle. He was a real cat.” When Petty sang “a song by Jimmie Rodgers, Merle Haggard or the Searchers,” Tench insists, “he wasn’t a dilettante, trying something on. He was for real.”

The last time Campbell talked to Petty was after the band’s September 17th concert in San Diego, aboard the flight to Los Angeles ahead of the Hollywood Bowl shows. “Tom got up and made a little speech,” the guitarist says, “like, ‘This has been the best tour. You guys were great. We’re not going to do any more long tours like this, but we have a lot of stuff we’re gonna do, because this is the best the band has ever been.’

“When he walked past me,” Campbell continues, “I put my arm out, I pulled him close to me and said, ‘I’m so proud of you. I know your leg has been killing you. You’ve been up there like a soldier, man.’ We had a nice hug and said we loved each other.” After that, at the Bowl, “it was backstage, ‘Hi, how you doing?,’ a little patter between songs.”

“It’s sad that he’s gone,” Springsteen says of Petty, “but it was nice to be alive in his lifetime.” And the work remains. “Good songs stay written. Good records stay made. They are always filled with the promise and hope and life essence of their creator.

“Tom made a lot of great music,” Springsteen points out, “enough to carry people forward.”

—

From issue #793 (December, 2017), available now.