“Don’t worry,” announces the warped robot voice at the start of Prince‘s 1999. “I won’t hurt U. I only want U2 have some fun.”

Is this the voice of God? Or Prince’s synthesizers talking back to him? Either way, this guy’s got his own idea of fun. And he spends the next 70 minutes building his spiritual and political philosophy around the urge to party. He sets off security sirens at the club by masturbating on the dance floor. He solves the nation’s evils by staging a sex-as-redemption ritual with his lady cabdriver in the back seat. He dances under the shadow of the mushroom cloud, as the double-drag warmongers finally hit the little red button and blow up the planet – but not before Prince squeezes in one more Saturday night of letting that lion in his pocket roar. He gathers musicians of different races and genders into a communal church, dedicated to the higher purpose of getting Prince more action. You can’t accuse the man of thinking small.

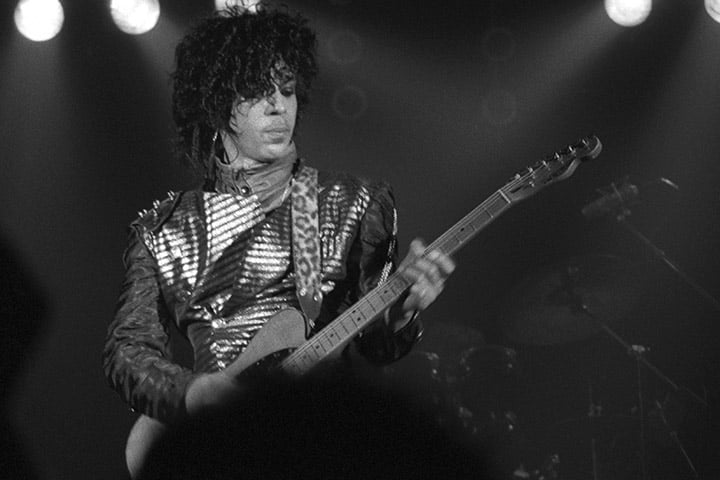

At just 24, Prince dropped 1999 in October 1982. In career terms, it was supposed to be his art album. Maybe he’d crack rock radio, setting him up to make his pop-crossover move next time. But the plan failed – because there was no way the pop audience could resist 1999. Prince ended up becoming a big-time star with his artiest, most extreme, most demanding music.

“I think he was trying to become as mainstream as possible, without violating his own philosophy, without having to compromise any of his ideas,” keyboardist Matt Fink told Rolling Stone in 1989 when the magazine included 1999 on its list of the 100 best albums of the Eighties. “To some extent, he was trying to make the music sound nice, something that would be pleasing to the ear of the average person who listens to the radio, yet send a message. I mean, 1999 was pretty different for a message. Not your average bubblegum hit.”

1999 was an old-school double vinyl album, just two or three songs per side, giving the grooves room to flesh out his liberation theology. Nearly every song has Prince uttering a full-fledged manifesto or two, preaching the “D.M.S.R.” gospel: Dance Music Sex Romance. The Led Zeppelin credo “Do what thou wilt” became Prince’s “Do whatever we want! Wear lingerie 2 a restaurant! Policeman got no gun! U don’t have 2 run!” And in case anyone accuses him of mere shock tactics, he explains his moral code in “Let’s Pretend We’re Married”: “I’m not saying this just 2 be nasty/I sincerely want 2 fuck the taste out of your mouth/ Can U relate?” Who couldn’t?

Prince recorded 1999 amid a creative frenzy that consumed him all through 1982, while he was simultaneously making albums for Vanity 6 and the Time. “I have the follow-up album to 1999,” he told Rolling Stone in 1985, describing his furious pace of work. “I could put it all together and play it for you, and you would go, ‘Yeah!’ I could put it out, and it would probably sell what 1999 did. But I always try to do something different and conquer new ground.”

Sessions were divided between Sunset Sound in Los Angeles, where he’d recorded Controversy, and the home studio in his purple house near Lake Minnetonka outside Minneapolis, which he’d recently outfitted with a 24-track recording system. “I think he found his groove,” recalled drummer Bobby Z, “and the groove never left.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Strange as it seems in retrospect, there was no reason to think his new music had any shot at pop radio. He was three years past his only Top 40 hit, “I Wanna Be Your Lover.” But he clearly wasn’t thinking in those terms – he made the music even more outrageous than the lyrics, experimenting with the newfangled technology of Oberheim synthesizers and Linn drum machines.

He’d obviously studied the latest New Wave records in the import bin. As guitarist Dez Dickerson recently told Billboard’s Michaelangelo Matos, Prince was inspired by “the New Romantic thing,” especially Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet, who were in rotation at First Avenue, the Minneapolis club immortalized in Purple Rain.

1999 came on as the ultimate New Romantic statement. It was the synth-pop album to beat all other synth-pop albums, in the year synth-pop took over. 1982 was full of futuristic electronic records mixing disco beats with arty concepts – from the Human League’s Dare to Yazoo’s Upstairs at Eric’s, from George Clinton’s Computer Games to Duran Duran’s Rio. Hip-hop went techno with Afrika Bambaataa’s “Planet Rock” and “Looking for the Perfect Beat” and Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message”; so did the goth-punk kids in New Order with their club hit “Temptation.”

But as any of these artists probably would have conceded, Prince topped them all, creating his own kind of nonstop erotic cabaret. Instead of just overdubbing instruments to replicate a live band, he built the tracks around a colossal synth pulse, which made 1999 one of the decade’s most influential productions. “Little Red Corvette” became such a massive pop hit, it’s easy to overlook how radical it sounded at the time. All through the song, you can hear the machines puff and hiss, as if Prince’s engines are overheating, with his studio as a Frankenstein lab full of sparks flying everywhere. It’s sleek on the surface, but the rhythm track keeps sputtering and threatening to blow up. It’s the sonic equivalent of George Lucas’ breakthrough in the original Star Wars movie – he figured out that the way to make droids look real was to make them dusty and dented, as if they’d gotten banged around on the job.

MTV was clearly a huge influence on 1999 – not just as a format for exposure, but as a source for the latest European synth sounds. Here was a network where David Bowie and Roxy Music were legacy artists while Depeche Mode and Adam Ant were bona fide stars. This place was made for him. A Flock of Seagulls – even their name sounded like a Prince lyric.

Also significant about MTV in 1982 was that it was a nationwide rock & roll network with black artists in the mix, and one ripe for a black art rocker like Prince to take over. Which he did. MTV played the “1999” video like it was manna from heaven. Radio still resisted – the “1999” single stalled short of the Top 40. But MTV played the video so heavily that it was even used in the network’s own stereo-demonstration ads. When “Little Red Corvette” went into rotation, MTV kept right on playing “1999,” even though both videos looked suspiciously like they were filmed on the same day with the same cast wearing the same clothes.

It didn’t matter. The network couldn’t get enough of the “Minnesota Monarch,” as MTV’s J.J. Jackson called him. (The nickname didn’t catch on, though “His Royal Badness” did.) By the time Michael Jackson came out with his much-ballyhooed “Billie Jean” video, Prince was already MTV’s signature artist.

When “Little Red Corvette” finally invaded pop radio in the spring, it broke the whole album, pushing “1999” back onto the charts and up to Number 12. “Little Red Corvette” was his love song to the girl with the pocketful of Trojans – and probably a trunkful of unpaid parking tickets. She drives him to a sex lair decorated with pictures of her conquests, which some repressed guys might take as a warning sign. But Prince figures it’s Saturday night – guess that makes it all right – and surrenders to her high-horsepower libido.

The title anthem didn’t play coy about the Cold War dread that infused 1980s pop. With a trigger-happy Republican administration in the White House, it was shocking to hear Prince’s synthesised kiddie voices gurgling the question “Mommy, why does everybody have a bomb?” “Delirious” sounds like the safe novelty Prince put on the album in case radio chickened out of playing “1999” (which it did at first) or “Little Red Corvette” (which took months to build into a blockbuster). But “Delirious” cracked the Top 10 that fall, with a six-note synth whinny that could make you laugh loudly before you even noticed the words.

Even the deep cuts are top-notch – “All the Critics Love U in New York” weighs in on that most bizarrely popular of Eighties topics: bitching out music critics. “Something in the Water (Does Not Compute)” is a haunting computer-blue ballad, with Prince moaning over dark-wave synths, as if his frantic bedroom schedule can’t fix the hole in his heart. “Automatic” and “Lady Cab Driver” are deeply melancholy sex jams – as in the moment when backup singers Lisa Coleman and Jill Jones announce, “I’m going 2 have 2 torture U now.”

Prince gives his bandmates vocal spotlights all over the album – he doesn’t join the first verse of “1999” until Coleman, Jones and Dickerson sing the opening lines. He credited his band on the cover – the words “and the Revolution” were scrawled backward – and included a sleeve photo of his racially and sexually integrated musicians. But as Dickerson said, “It was always part of the rhetoric. He wanted a movement instead of just a band. He wanted to create that kind of mind-set among the fans.” With 1999, Prince started a movement the whole world wanted to join.