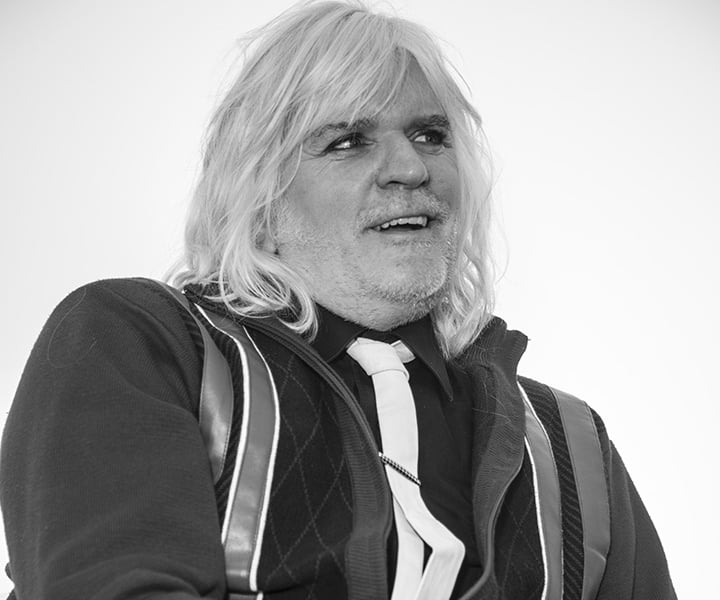

Steve Lucas is a vision of unrepentant rock & roll glory. Statuesque, platinum blond with just a hint of blue eyeliner, he’s dressed like a Harlem dandy complete with walking stick — a stylish necessity after a devastating injury in 2009. The last remaining member of Sydney punk outfit X has learned to live with death, betrayal, excruciating pain and commercial reward far short of his reputation. How? With a twinkle in his eye, that’s how.

Any kid in a Ramones T-shirt knows Radio Birdman, the Saints, the Birthday Party. X is a legend for aficionados. Do you take pride in that?

Yeah. The secret to our success is a total lack of success. Every time we had a chance to do something we fucked it up gloriously and just rolled on.

How deliberate was X as an act of rebellion?

Well, you had [drummer] Steve Cafiero, who cut his teeth as drum roadie for the Easybeats. [Bassist] Ian Rilen had just been booted out of Rose Tattoo. [Guitarist] Ian Krahe and I were 10 years younger and all we’d ever done was read Rolling Stone. So [Cafiero and Rilen] were already institutionalised: You get onto an agency, you make records, you get your three per cent, you go on tour and you shut up. Krahe and I were like, ‘Fuck that. There has to be another way.’ So they embraced our enthusiasm.

Your debut, X-Aspirations cast you as outsiders, victims of police harassment. How true?

Rilen wanted to be the bad boy. “I’ve been in Long Bay [Prison].” Oh really, how long were you in for? “Ah, they found some pot and I was in a holding cell for eight hours.” He would go out of his way to make trouble with the police. Krahe and I were into John Lennon’s outspokenness; the idea of rebellion. “Something in the Air”, “My Generation”, “Won’t Get Fooled Again”… those anthems were our lifeblood.

Krahe died in ’78, Cafiero in ’88… how did tragedy inform your resolve to continue?

Ian Krahe’s death was the first taste of death I had known. I had seen people [flirting with] death with smack, but it took six months for me to accept what dead really meant. We were doing a gig on Oxford Street the night it finally hit me and I just broke down. I remember Ian Rilen shaking me. “You cannot do this! You’ve got to take it like a fucking man!” We didn’t have words like “closure” then. The process was denial, breakdown, be a man, and move on.

X broke up countless times over three albums. Was there a single issue?

At the heart of it, Ian had had Rose Tattoo and “Bad Boy For Love” and he wanted that again. Now, X was becoming infamous but we weren’t a commercial band. Ian was chasing something.

Groody Frenzy, Double Cross, A.R.M, The Empty Horses, Los Trios Derros, Strawberry Teardrop, Pubert Brown-Fridge Occurrence … you’ve been a marketing nightmare as a solo name, haven’t you?

I had a manager for about three months and he said, “What you’ve got to do, Steve, is reinforce your name.” So just as the Groody Frenzy thing was coming out [in 1990], we had these huge [posters]: “Steve Lucas”. And honestly, I felt so embarrassed walking down the street. I just wanted to be in a band. The minute I call it Steve Lucas and the Blah Blah, it’s not a band.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Did the Groody posters work?

The single got into the Top 40 with a bullet and the record company went into liquidation. That was devastation number one.

Devastation number two? When my daughter was 18 months old, my wife took up with Ian Rilen. Then my fucking dog died. So it was a 1-2-3. “That’s it, I’m down for the count. I’m just gonna be a dad.” Music became a sideline. I did Bigger Than Jesus because I didn’t have to think about it.

You toured the US for the first time in 2010 under extreme circumstances. Care to recount that story?

I ruptured a disc in my spine. I went to an osteopath who basically squeezed all this shit in the disc, mainlining it right into my spinal column. My left leg was paralysed and I was starting to lose control of the right. The pain receptors in my brain were so traumatised they couldn’t switch off. Then I got a call saying, “We wanna do a vinyl release of X-Aspirations for America. Will you come?” I was taking 500mg of time-release morphine twice a day. I had a pharmacy in my carry-on.

How did you perform?

As long as I had my feet planted, I could stand and deliver. Twenty-one gigs in 23 days, under extreme duress. I began to wonder, “Am I a musician, or just some punch-drunk pug that just doesn’t know when to stay down?”

Did you consider giving up?

More than once. But what kind of message would that send to my kids? The pain was so excruciating I couldn’t be touched without wanting to scream. A Buddhist friend said, “The only way you’ll get over this is to learn to love the pain and what it’s giving you.” I remember waking up one morning and realising, “I define the pain. The pain does not define me. I’m gonna get better.”

X just played a 40th anniversary tour. We lost Rilen in 2006. You’re the last man standing. What makes you do it?

Who else is going to keep [their memory] alive? They lived their lives to a certain extreme that left them with no other recourse. Any number of times I could have been dead. I’ve gotta be here for a reason. Playing in X is as good as any.

—

Photograph by Matt Coyte. This interview is part of our Living Legend series. From issue #791.