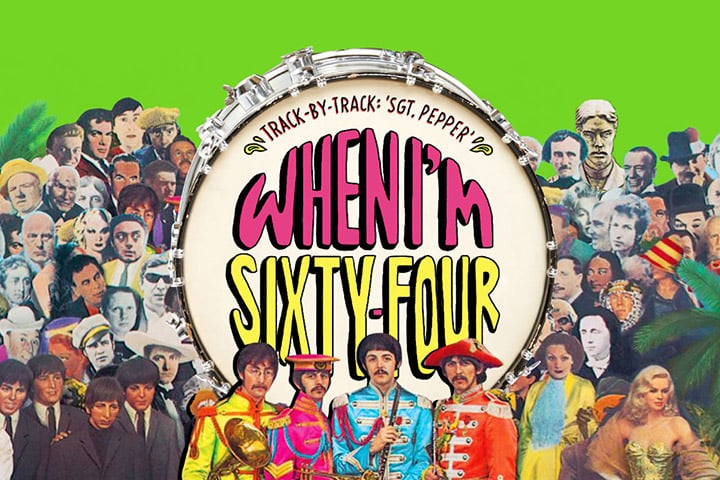

p>The Beatles‘ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which Rolling Stone named as the best album of all time, turns 50 on June 1st. In honour of the anniversary, and coinciding with a new deluxe reissue of Sgt. Pepper, we present a series of in-depth pieces – one for each of the album’s tracks, excluding the brief “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” reprise on Side Two – that explore the background of this revolutionary and beloved record. Today’s instalment tells the story of how Paul McCartney’s father’s musical past inspired the “rooty-tooty variety style” of “When I’m Sixty-Four.”

Alongside Elvis Presley, Little Richard and Buddy Holly, it’s important to cite Jim Mac’s Jazz Band among Paul McCartney’s formative influences. The obscure ragtime combo never cut a record, but it happened to be fronted by the future Beatle’s father, Jim. “My dad was an instinctive musician,” McCartney recalled in the Beatles Anthology documentary. “He’d played trumpet in a little jazz band when he was younger. I unearthed a photo in the Sixties, which someone in the family had given me, and there he is in front of a big bass drum. That gave us the idea for Sgt. Pepper: the Jimmy Mac Jazz Band.” Beyond inspiring the cover image, McCartney’s musical heritage would get an affectionate nod on the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band track “When I’m Sixty-Four.”

The elder McCartney got his showbiz start like his son: playing workmen’s dances around Liverpool as a teenager. Unfortunately, a wardrobe malfunction marred his band’s public debut. “We thought we would have some sort of gimmick, so we put black masks on our faces and called ourselves the Masked Melody Makers,” Jim related to Beatles biographer Hunter Davies. “But before half time we were sweating so much that the dye was running down our faces. That was the end of the Masked Melody Makers.” In their embarrassment, the group changed their name to Jim Mac’s Jazz Band. “I ran that band for about four or five years, just part time. I was the alleged boss, but there were no distinctions. We played once at the first local showing of the film The Queen of Sheba. We didn’t know what to play. When the chariot race started we played a popular song of the time called ‘Thanks for the Buggy Ride.’ And when the Queen of Sheba was dying we played ‘Horsy Keep Your Tail Up.'” The young Beatles would have a similar experience during an early gig backing a stripper. Unable to read her music – or any music, for that matter – they simply improvised on the spot.

Dental difficulties forced Jim to abandon the trumpet by the time sons Paul and Michael were born, but he filled the McCartney home with music played on a piano purchased from Harry Epstein – father of future Beatles manager Brian. Though self-taught, he possessed the flair of a gifted natural musician. “I have some lovely childhood memories of lying on the floor and listening to my dad play ‘Lullaby of the Leaves’ – still a big favorite of mine – and music from the Paul Whiteman era, old songs like ‘Stairway to Paradise,'” says Paul in the Anthology. “To this day I have a deep love for the piano, maybe from my dad: It must be in the genes.”

The sounds of the Twenties and Thirties, channeled through his father, became McCartney’s musical foundation. “I grew up steeped in that music-hall tradition,” he told author Barry Miles in the book Many Years from Now. “My father once worked at the Liverpool Hippodrome as a spotlight operator. They actually used a piece of burning lime in those days, which he had to trim. He was very entertaining about that period and had lots of tales about it. He’d learned his music from listening to it every single night of the week, two shows every night, Sundays off. … He had a lot of music in him, my dad.”

Jim encouraged his sons to learn how to play piano, noting that it would lead to plenty of party invites. McCartney was eager, but Jim refused to pass along his untutored technique. “I would say, ‘Teach us a bit,’ and he would reply, ‘If you want to learn, you’ve got to learn properly,'” McCartney remembers. “It was the old ethic that to learn, you should get a teacher.” But teachers conjured up images of schoolwork, hardly appealing for a young boy. “In the end, I learnt to play by ear, just like him, making it all up.”

Before long he was making up melodies of his own, one of the earliest being “When I’m Sixty-Four,” a jaunty tune that straddled the line between homage and parody. “I’d started fiddling around on my dad’s piano. I wrote ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ on that when I was still 16 – it was all rather tongue-in-cheek – and I never forgot it. I wrote that tune vaguely thinking it could come in handy in a musical comedy or something.” Largely written before Presley and the rest of the rock brigade had fully conquered British shores, it’s a fascinating look at McCartney’s early aspirations. “When I started songwriting, it wasn’t to write rock & roll. It was to write for Sinatra. It was to write cabaret,” he says in a 1992 episode of The South Bank Show.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

The song stuck around, becoming a jokey party piece in the Beatles’ early repertoire when they played Liverpool’s Cavern Club. John Lennon, rarely one to openly embrace the sentimental, shared fond memories of the tune to Hunter Davies. “It was just one of those ones that he’d had, that we’ve all got, really; half a song. And this was just one that was quite a hit with us. We used to do them when amps broke down, just sing it on the piano.” The Beatles’ former drummer, Pete Best, has also recalled Paul launching into the song during onstage power failures, giving authenticity to the line, “I could be handy mending a fuse when your lights have gone.”

“When I’m Sixty-Four” seemed doomed to wallow in obscurity until the fall of 1966. Jim had turned 64 that July, but more likely it was the recent spate of Twenties throwback groups – the New Vaudeville Band, the Temperance Seven and the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band among them – that made Paul reconsider his primitive composition. “I thought it was a good little tune but it was too Vaudevillian, so I had to get some cod lines to take the sting out of it, and put the tongue very firmly in cheek,” he told Miles “I did it in a rooty-tooty variety style.” In spite of, or perhaps because of, its age, it seemed to fit the psychedelic variety show McCartney had been conceptualising for the next Beatles album.

Work began on “When I’m Sixty-Four on December 6th, 1966, at EMI’s Abbey Road studios, with the Beatles recording a basic rhythm track. Though it had been nearly half a decade since they aired the song at the Cavern, they picked it up fast. “Because the group was already so familiar with the song, the backing track was laid down in just a couple of hours,” engineer Geoff Emerick recalls in his memoir, Here There and Everywhere: Recording the Music of the Beatles.

To flesh out the arrangement, Paul asked producer George Martin to arrange a breezy clarinet part. Martin immediately got the musical reference. “‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ was not a send-up but a kind of nostalgic, if ever-so-slightly satirical tribute to his dad,” he explained in 1994. “It is also not really much of a Beatles song, in that the other Beatles didn’t have much to do on it. Paul got someway ’round the lurking schmaltz factor by suggesting we use clarinets on the recording, ‘in a classical way.’ So the main accompaniment is the two clarinets and a bass clarinet, which I scored for him. This classical treatment gave added bite to the song, a formality that pushed it firmly towards satire.”

The song itself is perhaps the least complex on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, but it does contain one notable instance of studio slight-of-hand. “During the mix, Paul also asked to have the track sped up a great deal – almost a semitone – so that his voice would sound more youthful, like the teenager he was when he originally wrote the song,” writes Emerick. However, McCartney himself disputes this, maintaining it was done to make the track more buoyant. “I think that was just to make it more rooty-tooty; just lift the key because it was starting to sound a little turgid.”

The song was mixed down before the New Year, making it the first track on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band to be completed – though it nearly didn’t make it onto the album. “When I’m Sixty-Four” was provisionally earmarked as a potential B side to either “Strawberry Fields Forever” or “Penny Lane,” which were being produced concurrently. But after a lengthy stretch of no new Beatles releases, and whispers in the press that the band’s bubble had finally burst, Brian Epstein wanted to make a splash with their next single. “Brian was desperate to recover popularity, and so we wanted to make sure that we had a marvelous seller,” explains Martin in the Anthology. “He came to me and said, ‘I must have a really great single. What have you got?’ I said, ‘Well, I’ve got three tracks – and two of them are the best tracks they’ve ever made. We could put the two together and make a smashing single.’ We did, and it was a smashing single – but it was also a dreadful mistake.”

Upon its release on February 17th, 1967, the double-A-sided “Penny Lane”/”Strawberry Fields Forever” became the first Beatles single since 1962’s “Love Me Do” that failed to reach Number One in the United Kingdom. Adding insult to injury, it was blocked from the top spot by Engelbert Humperdinck’s overblown cover of the Forties chestnut “Release Me.” Martin believed the chart success was hampered by the fact that record compilers counted the two sides as individual entries, thus splitting the sales. In fact, the Beatles’ release outsold Humperdinck’s by nearly double. Still, Martin remained guilt-ridden for his part in breaking the so-called “roll” of Number Ones. “We would have sold far more and got higher up in the charts if we had issued one of those [songs] with, say, ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ on the back,” he later lamented.

There were no hard feelings from the band. When Martin turned 64 in January 1990, McCartney sent him a birthday greeting: a bottle of wine.