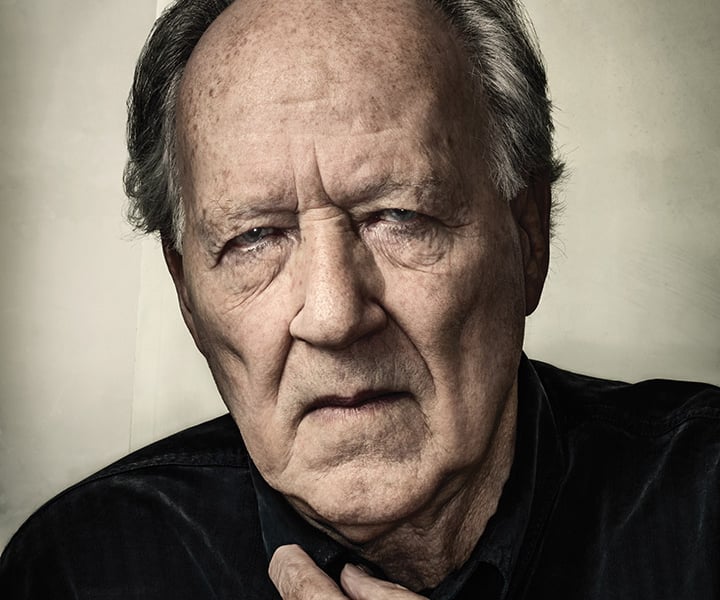

Not far from the big round dome atop the Griffith Observatory, leaning on a railing that overlooks the Greater Los Angeles sinkhole, the German director Werner Herzog, 74, removes a tissue from his pocket and dabs at his eyes. His eyes are leaking. They’ve been leaking for the past hour or so. The tear fluid builds up in the corner of one of his blue eyes, then starts to cascade down his cheeks, halted only when he dab, dab, dabs.

He does not explain this. In fact, him being Herzog, he would never explain this, if only because it’s not in his nature to even think about something so trivial and beside the point. Only one thing matters to him: his movies. He’s got two new feature films coming out: Salt and Fire, an ecological thriller, and Queen of the Desert, a biopic about the British explorer Gertrude Bell. Plus, just yesterday, he returned from Austria, where he opened a Herzog retrospective that includes everything he’s ever done, from his early career-establishers (1972’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God and 1982’s Fitzcarraldo) to his more recent documentaries (2016’s Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World, about the possible existential consequences of an Internet-driven world), along the way revealing much about what interests and fascinates him – in brief, everything. He’s made movies about nomads, auctioneers, televangelists, monks, hot-air balloonists, ski-jumping woodcarvers, volcanic eruptions, cave paintings, grizzly-loving (and eventually grizzly-eaten) loner outdoorsmen, desolate Antarctic snowscapes – the list does not end. He’s been called “a genius,” “a madman,” “a visionary,” “the last great hallucinator in cinema” – and that list does not end either.

Today, he’s frowning and speaking in his famous half-flat, half-amused Germanic voice. “Yes, they are showing all 70 of my films,” he says, “but there may be more. It depends on how you count. For example, some people count the eight films in my ‘Death Row’ series as one film. So, do you count it as eight or do you count it as one? I guess it depends on your mood.” He pauses. Then he says, “I’ve never counted them myself. I don’t care.”

Which is just like him to say, to display a good bit of interest in the mundane, then proclaim no interest whatsoever. On the other hand, there’s no curbing his ardor once he starts in on how his documentaries are so vastly different from almost everyone else’s, mainly because his contain made-up elements, which he believes is a good thing, since pure fact is apparently just another hobgoblin of the feebleminded.

“In the film I did about the oil fires burning in Kuwait,” he says, puffing up his chest a little, “it starts off with a quote from [17th-century philosopher and physicist] Blaise Pascal. And it’s a beautiful one. It says, ‘The collapse of the stellar universe will occur like creation, in grandiose splendour.’ But Blaise Pascal did not say that. I did.”

Without explaining how making up quotes improves anything, he swiftly offers another example, this one involving the radioactive albino mutant crocodiles that appear at the end of 2010’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams. Seems that while they are indeed albino, they’re not radioactive or mutant, Herzog snorts. “My producer said, ‘You cannot do that because if you do, one day they’ll take you away in a straitjacket.’ And I said, ‘Fine! That’s a moment I look forward to!’ ” He goes on, “Those who tell you we should be like the fly on the wall are losers. Losers! They make what I call ‘the accountant’s truth.’ But I am fascinated by the possibilities for a deeper stratum of truth, although please don’t ask me what I mean by truth, because nobody can answer that one. But, you see, we are creators. What I do is elevate the audience. I’m intensifying facts to such a degree that they start to get the glow of illumination for you. They acquire insight and poetry of an ecstatic nature, like medieval monks.”

A moment of silence follows. Herzog’s words hang in the air with the kind of significance that only he, with his even-keeled, softly forceful delivery, can bring to them. It’s the same delivery that inhabits his documentaries and films, and thus makes him and his movies seem intertwined and all part of some kind of ongoing public performance.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

A scene from Herzog’s 1992 documentary ‘Lessons of Darkness.’

The most important thing to know about Herzog is that his first childhood memory is of the Bavarian city of Rosenheim, during the last World War, engulfed in fire after a bombing raid in 1945, as seen at night from a distant hill, he and his older brother brought there by their mother, to witness the kind of destruction that had caused them to flee Munich and live in a remote backwoods Bavarian Alps village, no running water, no toilets, no phones, cut off from all civilisation but for this one surreal vision.

Right now, Herzog is looking out at the vast sweep of Los Angeles, but his thoughts are still on the fire.

“At the end of the valley,” he says, “you saw the sky orange and yellowish and red. And my mother said, ‘Boys, the city of Rosenheim is burning.’ The entire sky was pulsing. And I knew there was a big city out there burning. And it was more beautiful than anything.” Such was his first taste of the glow of illumination that is, in theory at least, at the heart of all his documentaries.

“My producer said, ‘You cannot do that because if you do, they’ll take you away in a straitjacket.’ And I said, ‘Fine! That’s a moment I look forward to!’ ”

As to the heart of the man himself, the stories most often trotted out to define him have always been of the look-at-Herzog-isn’t-he-nuts variety, and they are legion. He walked 1,000 miles to propose to his first wife. A random, errant bullet winged him in the gut during a live interview once (and to whom but Herzog could this ever have happened?) and he kept right on talking, brushing aside the wound as coming from “an insignificant bullet.” He started a film school called the Rogue Film School, said he preferred that his students be “people who have worked as bouncers in a sex club or have been wardens in the lunatic asylum,” and featured courses on the art of lock-picking and forging filming permits. He knows how to hypnotise chickens. He spent two years in the Amazon jungle trying to haul a steamboat over a mountain for Fitzcarraldo. Earlier, while filming Aguirre, the Wrath of God, the star of that film, the late, totally insane Klaus Kinski, threatened to leave the project. Herzog said he’d shoot him, and Kinski stayed put. When Kinski was writing his autobiography, he and Herzog, Roget’s Thesaurus in hand, collaborated on Kinski’s description of the director as “dull, humourless, uptight, inhibited… hateful, malevolent.” Also long-winded: “Even if his throat were cut and his head were chopped off, speech balloons would still dangle from his mouth.”

And yet what does any of it really say about Herzog, the pallor-faced, balding, slightly rumpled figure standing here today? In a sense, it all seems to obscure the man as much as reveal him.

Herzog and his family returned to Munich when he was 12; he began watching films, came across a 15-page encyclopedia entry on filmmaking and discovered his life’s purpose. He kick-started his dreams by stealing a camera from a Munich film school, with not a second’s regret. “I don’t consider it theft,” he once said. “It was just a necessity. I had some sort of natural right for a camera.” So, even then, he was full of himself. And today he says, “Very early in life, I have understood my destiny. My destiny has been made known to me. And I have a duty to it. They sometimes call me ‘mad.’ But that’s just a projection of things, maybe of my leading characters, onto the person who created them. If I could be anonymous, that would be best. But I don’t care. I don’t care whether they label me. The only thing that counts is what’s up on the screen.” He looks down at his feet. He goes on, “I own very, very few things. The shoes I’m wearing are the only shoes that I own, along with a pair of heavy boots and a pair of really good sandals. This is what I wear.” He plucks at his sweater. “I wear the same sweater all the time. It’s wool.”

Herzog on the set of ‘Fitzcarraldo,’ in which the fillmaker dragged a giant ship up a Peruvian mountain to get a shot.

His first film was a short, in 1962, titled Herakles, and featured bodybuilders intercut with scenes from a Le Mans car-race wreck that cost some 80 spectators their lives. “For me, it was fascinating to edit material together that had such separate and individual lives,” he once said, a technique that he’s used ever since, sometimes making it up as he goes along, what with his phoney crocodiles and all. Then, in 1972, came Aguirre, the Wrath of God, which follows a Spanish soldier, played by Kinski, as he searches for El Dorado, the lost city of gold, and only finds madness and death. It bombed and was immediately dropped by theatres.” ’This is it,’ ” Herzog says he thought. “ ’I’m fucked.’ ” In 1975, however, two small theatres in Paris picked it back up and started it on a sold-out run that lasted for two and a half years. “So, it caught on,” says Herzog, “but even then not very well, but a decade later it was rereleased and two decades later rereleased, and all of a sudden it became some sort of a household item. But it took 35 years.”

Through it all, he’s been married three times (“It has somehow been harsh to live with me”), had three kids, told one and all he doesn’t own a cellphone and said a bunch of other portentous stuff like, “Men are haunted by things that happen to them in life.”

And what haunts him?

“I don’t want to understand what haunts me,” he says. “I do not like self-inspection.”

He’s going on now about President Trump, saying, “He’s the first time you have a real independent. He’s turned against the Republican Party, and he’s vehemently against the media, justifiably so to some degree, and I find this a very significant novelty. I see significant changes and significant new approaches. Trump and Bernie Sanders stuck out because he’s authentic. And it’s mysterious how Trump is getting away with literally everything. I see it with great, strange fascination. Very, very unusual.” He refuses to specifically say whether he likes Trump or not, but it often sounds like he does.

Then he talks about the Internet and some of the dangers featured in Lo and Behold. “We are a civilisation that is overdependent on the Internet at a time when the population is at least one and a half times too big. If the Internet goes down, all the basic things of our civilisation will be wiped out. It’ll be like Hurricane Katrina [but] in New York, no electricity, no running water, tens of thousands of people roaming the streets in search for a toilet. There’s only Central Park for food, and only a few squirrels there.”

Left to his own devices, he’ll go on like this forever, spinning out his various visions of the world. After a while, however, it gets to be a little much. His distaste for self-inspection noted, perhaps it’s time to wander over that way again anyhow.

A scene from ‘Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World.’

Does he have any vices?

Lips purse. “No. Nothing comes to mind.”

What makes him happy?

A scowl, one that pulls together many of the folds and creases in his face. “Oh, happiness isn’t of so much importance to me.”

What is he afraid of?

“Fear is not in my vocabulary. It just doesn’t exist in me. The scarier a situation gets, the more calm I am.”

He once said, “In my profession, you have to know the heart of men.” So what about his heart? Does he know it?

His mouth turns down, his lips press hard, he shakes his head. “Look. I don’t circle around my own navel. I’m not interested in myself. You should not expose the deepest recesses of your own soul. It doesn’t do anyone any good.”

“They call me ‘mad.’ But I don’t care. The only thing that counts is what’s up on the screen.”

Before he goes, however, Herzog says a few more things about himself. He sometimes cries during movies, and once, while watching a silent film called La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, he fainted dead away, as he also tends to do whenever blood is drawn from his arm. He’s never tasted any kind of illicit drug and is not in favor of legal drugs either. “I have taken less than 10 aspirins in my whole life,” he says. He will enjoy a glass of red wine, but the last time he got drunk he was 13. He has no hobbies. “Not a one.”

He’s entirely single-minded, every action directed toward the re-creation, in one way or another, of the fires that burned Rosenheim to the ground.

While promoting Grizzly Man, “My wife, Lena, took a photo where you can see a grizzly bear right behind me. She was worried about my safety. But I couldn’t care less. I only disliked the situation because the bear was so close that I could smell his very foul breath. It’s a very foul breath. So I didn’t like that. But that was the only thing.” He pauses, then goes on, “I’m not that interested in whether I perish or not. It would be of very minor significance.” As long, of course, as his films, all 70 or 78 of them, he’s never counted, survive his bloody mauling and stick around to glow with such illumination as only he alone is capable of producing.