Over the last week, N.W.A’s fierce indictment of racial injustice, “Fuck tha Police,” has become the anthem of a revolution, as thousands all over the world have taken to the streets in outrage over the wrongful killing of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police. Protesters have scrawled the song title on the homemade signs they wave and spray-painted it to walls. They’ve also been playing the 32-year-old track, which appeared on the group’s landmark Straight Outta Compton LP, so much that it experienced a nearly 300 percent uptick in streams.

That statistic doesn’t sit particularly well with one of the song’s cowriters. “This shit is unfortunate,” MC Ren says on a call shortly after a memorial for Floyd was televised. “A lot of people would be happy that they song gets streamed, but it’s unfortunate, because look how it came about: George Floyd — that was some bullshit. Enough is enough.”

Although N.W.A first raised eyebrows when MTV banned the video for “Straight Outta Compton,” it was “Fuck tha Police” that gave the group its legacy. In about six minutes, MCs Ice Cube, Ren, and Eazy-E serve as prosecutors against the overzealous LAPD, accusing cops of pulling them over in their cars and raiding their homes, over a hard-hitting beat while the track’s producer, Dr. Dre, presides as judge. “Fuck the police comin’ straight from the underground,” Ice Cube raps. “A young nigga got it bad ’cause I’m brown and not the other color, so police think they have the authority to kill a minority.” In Ren’s verse, he raps, “Taking out a police would make my day, but a nigga like Ren don’t give a fuck to say… fuck the police.” Both Ren and Cube were only 19 years old when they recorded the track, which has taken on new life in recent years.

Streams of “Fuck tha Police” surged in late 2014 and early 2015 — according to Alpha Data, the analytics provider that powers the Rolling Stone charts — as people protested and mourned the deaths of many unarmed black men who died from the actions of policemen, including Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York and Freddie Gray, in Baltimore. When Black Lives Matter held a vigil to honor Brown on the one-year anniversary of his death, streams of the song had increased nearly 44 times from the week of his death. The track experienced another surge in January 2016, when Black Lives Matter led a march in San Francisco ahead of Super Bowl 50. Streams of the song have continued to ebb and flow in the months since then as stories of police brutality became national news.

When considering the longevity of “Fuck tha Police,” Ren says it means as much to him now as it did three decades ago. “It’s still the same message,” he says. “It’s the same thing and it’s gonna have the same message after I’m gone.”

Over the years, Ice Cube has echoed Ren’s viewpoint. “That song is still in the same place before it was made,” the rapper said in 2015. “It’s our legacy here in America with the police department and any kind of authority figures that have to deal with us on a day-to-day basis. There’s usually abuse and violence connected to that interaction, so when ‘Fuck tha Police’ was made in 1988, it was 400 years in the making. And it’s still just as relevant as it was before it was made.”

“It seemed like all throughout junior high school, high school, [police] would just fuck with you for no reason,” Ren says. “It was like, if you black, you young, you in the hood, you in the ghettos of America, you just get fucked with. What you hear on the record is all the frustration, all the times getting harassed, getting pulled over for no reason at all, getting disrespected, having them try to disrespect your parents all because of your skin color. All of that builds up and you make a record. But we never thought the record would be around today with people still playing the record and into it. But shit, to me, it’s a perfect protest song.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

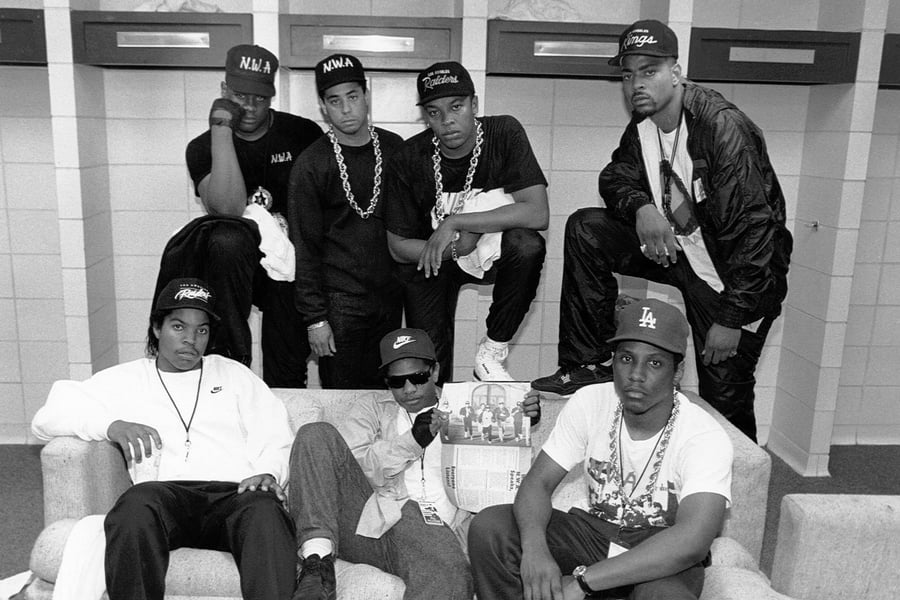

N.W.A’s MC Ren at the Chicago stop of the ‘Straight Outta Compton’ tour in June 1989. (Photo By Raymond Boyd/Getty Images)

Ice Cube has said he had the idea for song early in his time with N.W.A, but that Dr. Dre was reluctant to record it since he had been in and out of county jail and didn’t want to be hassled more because of a song. Dre came around to the idea of it after he and Eazy-E were busted for shooting paintballs at people waiting for a bus. “The cops caught us and we were face down on the freeway, with guns pointed at us,” Dre recalled in 2007. “We thought it was bullshit. So we went to the studio and created the song.”

“At the time, Daryl Gates, who was the chief of police over at the LAPD, had declared a war on gangs,” Ice Cube recalled in 2015. “A war on gangs, to me, is a politically correct word to say a war on anybody you think is a gang member… It meant a war on every black kid with a baseball hat on, with a T-shirt on, some jeans and some tennis shoes. So it was just too much to bear, to be under that kind of occupying force, who was abusive. It’s just, enough is enough. Our music was our only weapon.”

The group discussed Dre and Eazy’s incident at the apartment Dre and DJ Yella shared in Paramount, California, and headed out to the studio to record it quickly. Rapper the D.O.C., who co-wrote much of Straight Outta Compton, remembers when Cube brought the song concept back up again. “When he pulled it out, the title of the song just moved everybody in that space that day,” he says. “And we dedicated that day to build that feeling out.”

“We would go to the studio, Dre would put the beat on, and Cube would go in the corner and I would go in the corner and we would just write our shit,” Ren remembers. “When we was doing ‘Fuck tha Police,’ we didn’t know it would be as big as it was. We knew we wasn’t getting airplay.”

The song took on a new importance, though, when the assistant director of the FBI mailed a letter to Priority Records complaining about the song. “Law enforcement officers dedicate their lives to the protection of our citizens,” it read, “and recording such as the one from N.W.A are both discouraging and degrading to these brave, dedicated officers.” Straight Outta Compton was already a platinum-certified hit that had made it into the Top 40 of the Billboard 200 at the time, but Priority publicized the letter, and the track became an underground hit. “Shit, when we got the letter from the FBI, that’s when we knew right there that shit was big,” Ren says. “From then on out, it’s just been on.”

“Eazy loved the letter,” the D.O.C. recalls. “The idea was to make a point known, and everybody got the point all the way up to the highest cop.”

Despite the controversy, N.W.A usually kept the song out of their set lists when they performed live. The movie Straight Outta Compton depicts one of the rare times the group played it, in Detroit in 1989, when authorities there specifically told them not to. “The police chased us down and threw us in a little room and we sat there for an hour,” the D.O.C. recalls. “And then they come ask everybody for autographs. I think everybody but Cube obliged. He was the only guy that said, ‘Fuck y’all.’ He was always 1,000 percent true to his shit.” Similarly, Ren adds that whenever he has met cops, they’ve told him they like the song.

After news of the FBI letter got out, the song’s legacy ballooned. Bone Thugs-N-Harmony and Rage Against the Machine both covered it, and 2Pac, the Prodigy, comedian Chris Rock and countless others have sampled it. The screenwriters of the mockumentary Fear of a Black Hat parodied it in the movie, and YG recently took the song title and built his own George Floyd protest anthem out of it.

“It’s crazy how we were getting criticized for this years ago,” Dr. Dre said in 2015 of “Fuck tha Police.” “And now, it’s just like, ‘OK, we understand.’ This movie [Straight Outta Compton] will keep shining a light on the problem, especially because of all the situations that are happening in Ferguson and here in Los Angeles. It’s definitely going to keep this situation in people’s minds and make sure that everyone out there knows that this is a problem that keeps happening still today.”

After Ice Cube left the group in 1989, N.W.A recorded a “Fuck tha Police” sequel, “Sa Prize (Part 2),” on their 100 Miles and Runnin’ EP the following year. Ren is the first to say the original “Fuck tha Police” is the classic, but one of his lyrics from “Sa Prize” still resonates with him: “You call that right but when you’re black there’s no right.”

“There ain’t no right,” he says. “Today, you could have all the money in the world, [but] to the police, if they pull you over, you just a nigga. So you don’t have no rights. Like KRS-One once said, ‘There can never be justice on stolen land.’ This problem is not gonna go away until people realize how big a problem it is and how the problem got created. A lot of people don’t want to talk about it. But hopefully with all this protests worldwide, it will make people want to talk more. Because if they don’t, it’s gonna be a bigger problem. I know they don’t want no armed revolution.”

“Racism is just the symptom, but the fight is economic,” the D.O.C. says. “Black people have been marginalized and kept away from the economics of this country. I think people are starting to understand that and are trying to figure out how we can change that and allow everybody to join in this game of capitalism. That more than anything else is going to solidify people of color to really care about peace in their own neighborhoods, policing their own streets, not unlike the Black Panther party were doing back in the Sixties. [The Black Panthers] weren’t going to allow rogue police to come into their neighborhood and do the stuff these guys are doing to George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery or Breonna Taylor. You couldn’t have done that in the Panthers’ neighborhood. They weren’t going to allow it.”

Ren hasn’t gone out to any of the George Floyd protests, because he feels with the pandemic that “it’s too much shit,” but he supports the people in the streets. “I’m protesting in spirit,” he says. “I’m protesting with my song, ‘Fuck tha Police.’” He supports protesters’ calls to defund police as well as the need for better training, but mostly he wants to see justice for Floyd. “These motherfuckers got to pay,” he says, referring to the four officers involved in Floyd’s killing. “I saw something the other day, saying, it’s going to be hard to prosecute ’em. Man, if them motherfuckers get off, come on. You think it’s bad now, this is just the appetizer.”

Like Ren, the D.O.C. hasn’t attended any protests, but he’s currently working on a plan to effect change for people of color locally in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, where he lives. And he’s hopeful people all of the world who are protesting seize the opportunity to effect change and find focus. “You have to understand what it is you want, create a plan for what you want, and don’t allow them to give you any less than what it is you want, and that’s it,” he says. “Once you get a seat at the table, just like other communities, you will no longer allow [killings like] George Floyd’s [to happen].”

Ren, though, is less optimistic. “It’s unfortunate somebody had to lose they life for [streams of ‘Fuck tha Police’ to go up], but it’s going to continue to happen,” he says. “That shit will happen long after I’m gone and Cube gone: People will still be saying, ‘Fuck the police.’ You’ll see it on posters. You’ll see it on the walls. People will listen to it again, because police brutality is never gonna end in this country for black people. Hopefully something will change, but black people have been getting killed for so long. Since we came to America, we’ve been getting lynched and shit for no reason at all. It’s like, when do this shit end?”