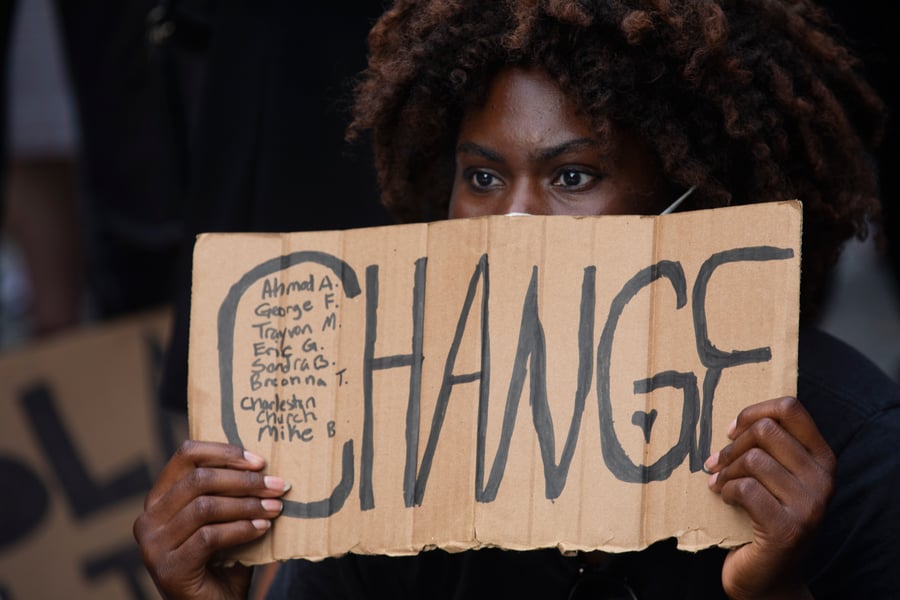

Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang made no mention of silence, let alone a black box, when they called on their peers in the music industry to devote Tuesday, June 2nd, to a new initiative, #TheShowMustBePaused. The idea was to force the industry — which is built on black talent, but still largely run by white people — to take a long look at itself and consider, perhaps, where the same white supremacy and privilege that led to the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and others, may be lurking in its own structures and practices.

But by Tuesday, the idea behind #TheShowMustBePaused had spread beyond the music industry and was being widely referred to as Blackout Tuesday. Thomas and Agyemang’s call to pause business as usual for a day of reflection had morphed into a vague notion of a social media blackout — an expression of silence in solidarity with protesters and people of color that took the form of a black square. As it turned out, many of the black squares posted by artists, labels, brands, celebrities, and individuals were also tagged #BlackLivesMatter, and the deluge ended up burying crucial information and resources for protesters and organizers.

“This is not helping us. bro who the hell thought of this??” Lil Nas X tweeted in response to the black square backfire, echoing a growing chorus of displeasure among artists. “Ppl need to see what’s going on.” (The rapper would later add, “What if we posted donation and petitions links on instagram all at the same time instead of pitch black images.”)

The mistake capped off a confusing four days for the music industry as it tried to find a proper response to the latest spate of police killings of unarmed black people and nationwide protests. When Thomas and Agyemang, two black women and music-industry vets, shared their idea for #TheShowMustBePaused late last week, they wrote in an opening salvo that their mission was to “hold the industry at large, including major corporations and their partners who benefit from the efforts, struggles and successes of Black people accountable. To that end, it is the obligation of these entities to protect and empower the Black communities that have made them disproportionately wealthy in ways that are measurable and transparent.”

As protests and police violence intensified over the weekend, the major labels — Warner Music, Sony Music, and Universal Music — and their imprints signed on to the initiative. In social media posts and internal memos to staff, they decried racism and injustice, and said that they would spend Tuesday forgoing work to come up with plans of action, causes to support, and/or task forces to form. Soon, companies like Spotify, Apple Music, TikTok, and SiriusXM, as well as the Recording Academy and major talent agencies like WME and CAA, shared similar statements, stating they too would observe Blackout Tuesday.

What exactly that meant, however, was up for debate, and the more momentum Blackout Tuesday gained, the further it seemed to grow from Thomas and Agyemang’s original intentions.

In the days before Blackout Tuesday, participating labels and corporations scrambled to make their subsequent actions align with their posted rhetoric. TikTok offered one of the more comprehensive plans on how they would observe the day, pledging $3 million from their Community Relief Fund to various nonprofits that offer aid to black communities. They also addressed recent criticisms of the app, some of which predated the protests, including an apology to black creators who felt unsupported, and another for a glitch that disrupted the #BlackLivesMatter and #GeorgeFloyd hashtags.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

#TheShowMustBePaused pic.twitter.com/JHTUG34Ibj

— theshowmustbepaused (@pausetheshow) June 1, 2020

Live Nation gave an undisclosed amount to the Equal Justice Initiative, while Sony said it would match employee donations to more than 30 social-justice charities throughout June. On Wednesday, Warner Music Group and the foundation run by its primary owner, Len Blavatnik, announced a $100 million fund benefiting causes “related to the music industry, social justice and campaigns against violence and racism.” Other labels like RCA and Interscope Geffen A&M pledged donations as well, though neither specified specific groups or dollar amounts.

At Universal Music Group, CEO Lucian Grainge appointed the label’s top counsel Jeff Harleston as the leader of a new company task force meant to address issues of inclusion and social justice. “[E]verything will be on the table,” Grainge said. The systemic nature of the problems are just too critical to leave anything off.” Sony kicked off a full day of programming for its employees with a town hall hosted by its diversity initiative HUE, during which employees were encouraged to “express their feelings about the recent state of affairs, raise points of concern, and suggest ways for Sony to implement change.”

Epic Records Chairman and CEO Sylvia Rhone also led a town hall to “discuss the impact of recent events and the importance of taking a stand for our communities and ways for individuals to make a difference both now and in the future.” And Columbia Records CEO Ron Perry, whose label was one of the first to post its show of support to social media, brought in George Floyd’s lawyer Benjamin Crump for a two-hour virtual discussion and a Q&A with label staff on the deaths of Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and other black victims killed by police.

Kehlani and Lil Nas X were two of the most prominent voices to weigh in on Blackout Tuesday. (Photo: Rob Latour/Shutterstock; David Fisher/Shutterstock)

But many in the industry utilized platitudes in their show of solidarity, and few specified how their day of “action and reflection” would translate to monetary support and beyond. The Recording Academy — which has faced a steady stream of criticism over its own issues with diversity and inclusion for several years and only just welcomed its first diversity officer last month — stated that it would use Blackout Tuesday to “reflect, as we know we can all be better … do better” and “join our colleagues in the music industry to make our voices heard as we commit to the long-term work required to drive positive changes.”

Major streaming services including Apple Music, Spotify, and Amazon Music offered similar statements, promising to “use this day to reflect and plan actions to support black artists,” to “stand with the Black community… in the fight against racism injustice and inequity,” and to “listen, learn and find more ways we can act in the ongoing fight against racism.” Amazon Music added that it would contribute to organizations combating racial injustice, without specifying which ones or how much, while Spotify said it would match employee donations to various groups. Only YouTube got specific, pledging $1 million to the Center for Policing Equity.

In an effort to translate the visual meme of the black square to the airwaves of radio, the satellite giant SiriusXM cut the music on its channels for three minutes at 3 p.m. ET on Tuesday: “One minute to reflect on the terrible history of racism, one minute in observance of this tragic moment in time and one minute to hope for and demand a better future,” the company said in a statement. In an internal memo, SiriusXM and Pandora CEO Jim Meyer said the company will “continue to use our platform to encourage dialogue, debate, tolerance and understanding.” There was no mention of a charitable donation.

Ultimately, in lieu of direct donations or, perhaps, a pledge to increase royalty payments to artists and songwriters whose music powers the streaming economy, Spotify and Apple Music chose to mark Blackout Tuesday with new content instead. Apple Music suspended its regular Beats 1 Radio programming and pushed a playlist featuring black artists called “For Us, By Us.” Spotify replaced the covers of its top playlists like Today’s Top Hits, RapCaviar and “all of our urban and R&B playlists” with the ubiquitous black square. And to select playlists, it added a new “track” — eight-minutes-and-46-seconds of silence as “a solemn acknowledgement for the length of time that George Floyd was suffocated.”

Among the deluge of black boxes in the #BlackoutTuesday hashtag were a collection of A-list artists, including the Rolling Stones, Bon Jovi, Gwen Stefani, and Drake. However, many others begged for more transparency, action, and information. Kehlani — who has used her platform to provide resources for protesters — pointed out the mixed messaging and the lack of credit given to Thomas and Agyemang. Bon Iver called the exercise “tone deaf” in a since-deleted tweet, while St. Vincent and Noname alerted people to how the boxes were drowning out information for organizers. “Niggas care [too] much about the aesthetics of they [Instagram] page to post productive information needed during this time. shit wild,” the Chicago rapper wrote.

https://twitter.com/noname/status/1267836037515993088

The Weeknd, who has donated more than $500,000 to various Black Lives Matter causes, urged industry partners and execs to not only donate, but publicize how much they were committing. “No one profits off of black music more than the labels and streaming services,” he wrote. “It would mean the world to me and the community if you can join us.”

Even before organizers shared the Blackout Tuesday call to action, though, many young artists stepped up to show solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement as well as the protesters fighting against systemic racism and police brutality. Ariana Grande, Lauren Jauregui, Harry Styles, and YG have marched alongside the movement. Halsey brought medical supplies and helped nurse wounds from rubber bullets and batons police wielded against protesters. SZA has used her social media platforms to share pertinent information with protesters to help them stay safe as curfews loom over many major cities. John Legend, Common, the Weeknd, Lizzo, and Talib Kweli were among the entertainers who signed an open letter urging local governments to defund the police in favor of increasing spending on health care, education, and other community programs.

“No one profits off of black music more than the labels and streaming services” — The Weeknd

That letter was released by activist Patrisse Cullors, a co-founder of Black Lives Matter and a founding member of the Movement 4 Black Lives, and it pulls into sharp focus the most glaring omission from most corporate statements released in support of Blackout Tuesday: the police killing innocent black people and brutalizing protesters with military-grade equipment. Interscope RCA A&M gets a participation trophy for name-checking the organization JusticeForBigFloyd.com and borrowing some of its language, “Police violence must not go unchecked.” But the prize for the most egregious exclusion goes to Spotify, who hawked their “8-minute, 46-second track of silence as a solemn acknowledgement for the length of time that George Floyd was suffocated” without mentioning the cops that killed him.

One place the police were brought up? The first sentence of Thomas and Agyemang’s mission statement.

Amid all the confusion of Blackout Tuesday, Thomas and Agyemang did not give any interviews and were publicly silent — save for a clarification of what Tuesday was actually about that they were forced to post: “Please note: the purpose was never to mute ourselves. The purpose is to disrupt. The purpose is a pause from business as usual.”

But the duo was hardly laying low. Throughout Tuesday, they hosted a well-attended summit via Zoom, with four distinct panels where black and people of color label employees, executives, artists, and fans shared what they wanted to change in the industry at large. During the summit, attendees expressed a desire for more regular, open communication in hopes of building both a community and a support network that could ensure a better future for non-white people in the music business.

For the original organizers, their corner of #TheShowMustBePaused unfolded as they wanted: A dialogue was opened and a safe haven for the industry’s black employees, executives, and artists was established. While the far reach of Blackout Tuesday was often buried beneath a corporate din that lacked transparency and conviction, one important question came to light: What does an industry built upon black music need to do to support and uplift the black people in it? The vague responses from labels and corporations stirred up anger from already skeptical onlookers, but that anger may be exactly what’s needed to push further.

Additional reporting by Jason Newman